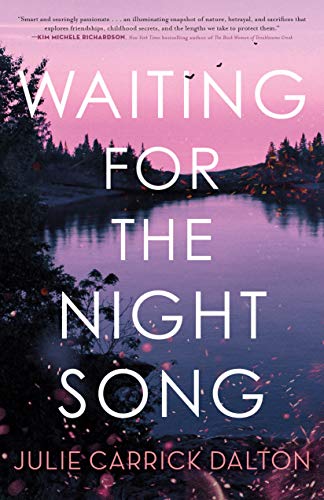

Waiting for the Night Song

“Dalton has created a page-turning thriller with undertones of contemporaneous, serious, societal, and academic issues.”

This debut novel Waiting for the Night Song by Julie Carrick Dalton is an impressive achievement. The author situates her novel in rural New Hampshire (where she was born and still lives), which was not named the Granite State on a whim. She uses the multi-layered granite rock that covers the land, laid down over millennia, as an objective correlative for the layers of secrets and mystery the protagonist, Cady Brady, has built to cover the potentially shattering secret of her childhood. A secret that haunts her nights and to a lesser extent the days of her thirty-something life.

An entomologist and forestry scientist, reclusive Cadie spends weeks and even months in remote forest locations in New Hampshire and elsewhere, tracking the movement of pine beetles as they move inexorably north, through New Hampshire and into Canada. Devastating forest fires follow in their path. The beetles have already decimated trees in California, Colorado, and elsewhere, and the fires followed. Now they are in the forests around Cadie’s childhood home, Maple Crest, leaving a warning in the lacy patterns they bore into pine bark. Caddy uses her research and map modeling to warn communities, other scientists, and local forestry departments to brush cut and clear the dead trees:

“Caddie squatted in front of the tree, steadying herself with one hand against the broad trunk. The doomed pine tree offered Cadie a way forward. She could prove her theory about beetles . . . But the tree also suggested her worst case might be playing out in her hometown.”

Yet it is a hasty text message from her childhood best friend that sends her back to her hometown, where she has not visited for decades. Uneasily they reconnect, but then it feels right again:

“Daniela let her head rest against Cadie’s, their shoulders pressing together. The tightness in Cadie’s chest loosened. She allowed herself to inhale a deep breath that stretched her lungs until they hurt, and oxygen rushed into the hidden spaces she had closed off for decades.”

A complex and well-plotted novel, Waiting for the Night Song intersperses chapters of present-day Cadie and her reunion with her childhood friend, Daniela, with chapters of scenes from their idyllic childhood, spent mainly one summer on the New Hampshire lake where they both live until one afternoon it is no longer an idyll and events destroy Cadie’s tranquil peace of mind. Adeptly the author maintains her grip on the plot details and suspense until the end.

Further, Dalton combines descriptions of natural beauty, love of and a sense of place, and enduring friendship that survives decades of no contact. Interwoven into the fabric of the novel are depictions of the strength of family ties, past and present. Fierce protective instincts of mothers and their precious, precocious children. Namely, Daniela’s 13-year-old daughter, Sal, an ardent champion of environmental protection and Piper, a young grad student researching the effects of climate change on avian habitat in forests, particularly the Bicknell’s thrush. Piper wants Cadie to share her data but Cadie is reluctant . . . yet not dismissive. She can’t imagine herself as a motherly mentor. But she is all too aware that the song of the Bicknell’s thrush has disappeared from “her” forest since her childhood. She misses the sound, and Piper’s ideas seem rigorous and well thought through:

“Piper bounced up next to Cadie and tilted her head to look up at the treetops. ‘They could come back here, you know. They often show up after fires and help rebuild. They’re industrious critters. There’s still a population of them around here. But they’re coming back from the Caribbean in smaller and smaller numbers every spring because of all the hurricanes and deforestation there. And our temps are getting higher, driving them north to Canada.’

“The hollow space in Cadie’s chest pressed against her lungs, a loneliness left behind by the tiny bird and everything else that had vanished from Cadie’s life. She bit her lower lip to quiet the unexpected quiver.

‘I miss them too,’ Piper whispered.”

Additionally enfolded into the novel, albeit sparingly, are themes of the dismissal by officials of scientific evidence, harsh treatment of “illegal” immigrants, racial tensions—and they all add heft, even though at times portentous argument, to this thriller. These pages hinder its pace, although the novel is mainly a page turner.

As Cadie had warned the officials in the town that it will come, a huge forest fire—out of control—threatens Maple Crest and helps to bring the novel to a climatic ending, burning away old loyalties and misplaced assumptions and allowing for new, more realistic expectations to take their place.

Fire, as T. S. Eliot wrote in famous lines in Little Gidding, one of the Four Quartets: fire both purges and purifies. So it is in this novel; a destroyer and a natural phenomenon that allows for rebirth. Thus, the novel ends:

“A high-pitched, erratic flute spiraled down from the charred limbs above her. The melody rocked like water cascading over rocks only to swoop upward at the last second, asking a question that needed no words. A Bicknell’s thrush. Cadie chocked on the ashy air and wiped her wet eyes.”

Dalton has created a page-turning thriller with undertones of contemporaneous, serious, societal, and academic issues.