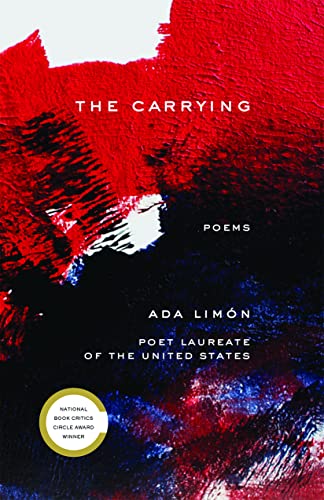

The Carrying: Poems

“Reading Limón’s new book, The Carrying, is as startling and as easy as walking into an unexpected, haunted room in a house you thought you already knew.”

Ada Limón’s poetic reputation is already well-established. Her 2015 collection Bright Dead Things was a finalist for both the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Still, there’s an aura of Very Serious Art which can obscure the work of acclaimed poets. In that mist, their writing is Important and Difficult, ineffable, something to be considered and meditated on, but not enjoyed.

Wave away that aura. Shake it off. Reading Limón’s new book, The Carrying, is as startling and as easy as walking into an unexpected, haunted room in a house you thought you already knew. Her language is conversational. Every moment is familiar, alienated only in the beat afterward when we look back to consider what’s just been said.

Much of the emotional force of The Carrying emerges from animals. They’re everywhere in these pages, friendly and familiar, but ancient, too. The book begins with Eve “walk[ing] among / the animals and nam[ing] them — / nightingale, red-shouldered hawk,” as she wishes for a reciprocal moment. There is no dominion in this conversation; it isn’t Man giving names to all the animals. Instead, it’s a process of recognition and longing, a realization of how deeply women and animals are connected.

That connection persists. Animals don’t dominate the text, which touches on infertility, on race and identity, on money and love, but the animals always return. In “The Vulture & the Body,” Limón begins, “On my way to the fertility clinic, / I pass five dead animals.” Here is an ordinary car trip, through the Kentucky countryside to a deeply modern, tech-driven venue, but the animals are still present, however mutilated. They’re crushed by the same technology on which we rely. Limón won’t let go of the injustice: “the sonogram wand showing my follicles, he asks / if I have any questions, and says, Things are getting exciting. / I want to say, But what about all the dead animals?”

The culture around her demands compartmentalization. Animal suffering and environmental degradation are terrible, of course, but as a proper citizen she should be able to put them to the back of her mind. Her function as a woman is childbearing, and that’s coming, maybe. Yet still, she wonders, “What if, instead of carrying / a child, I am supposed to carry grief?”

That pair of lines, separated across a stanza break, bring everything to a momentary stop. All the white-space gaps that text can throw up won’t stop such an idea.

The question of fertility runs through the poems without ever becoming an obsession. In “Would You Rather,” Limón writes, “and still I’m making a list of all the places / I found out I wasn’t carrying a child.” Still, a page later the next poem names itself, “Maybe I’ll Be Another Kind of Mother.” There’s value in loving without children. The film she watches, unpregnant, is a suggests otherwise. It centres on a man “somewhere saving the world, alone, / with only the thought of his family to get him through. The film will be forgettable.” In the absence of a child, there are still animals: “I’ll come home and rub my whole face against my dog’s / belly; she’ll be warm and want to sleep some more.”

Each poem is powerful on its own, and each can be read individually, but there’s great joy in devouring this book in just one or two sittings. As a collection, The Carrying is a quiet process of discovery: a single life and a series of worlds. The grief of childlessness balances against the joy of animals’ existence. Love persists across different locations and generations (even if this generation will, for this branch of the family, be the last). This is a book for both poetry fans and those who thought that poetry was too difficult and alien to comprehend, but who wouldn’t mind being proven wrong.