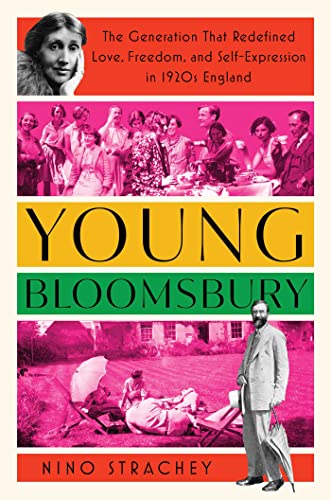

Young Bloomsbury: The Generation That Redefined Love, Freedom, and Self-Expression in 1920s England

“Pithy quotations and racy gossip exhilarate Young Bloomsbury.”

In the eyes of American literary critics and cultural historians, Bloomsbury—the subject of Nino Strachey’s new book—can look like the British counterpart to the Greenwich Village bohemians of the 1920. Brits probably will dislike that linkage, and indeed it might be unfair to both the groups on both sides of the Atlantic. They each had their own unique forms of expression. There was no Bloomsbury John Reed, the journalist who went to Russia and extolled the Russian Revolution in Ten Days that Shook the World. Also, there was no Greenwich Village novelist as avant-garde as Virginia Woolf, one of the mothers of modernism.

Nino Strachey’s new fast-paced book hints at the long-lasting appeal of the Bloomsbury figures she writes about, though she doesn’t go nearly far enough to explain cultural longevity. She doesn’t get out of her own bubble and look much beyond London and its environs, and she doesn’t make helpful observations about similar cultural manifestations.

The Bloomsbury iconoclasts and the bohemian crowd in Greenwich Village were both linked to particular urban places. They both mocked the conventional morality of their time, and they both nurtured talented writers and even a genius or two.

Like the original Parisian bohemians of the 19th century, Bloomsbury and the Greenwich Village crowds both formed tight-knit communities, entwined their lives with one another, created lasting works of art, and served as archetypes for future rebels.

As one admirer of Virginia Woolf and her friends observed, “members of both groups early on thought about and lived out many anti-Victorian taboos, broke the law and broke old fashioned mores which are still hanging around, even now.”

To this day, Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic occupy public offices, pulpits and plutocratic realms and want to repress individuals unwilling to fit into little boxes. Hence, the timeless appeal of the bohemians, the Bloomsbury folk, and more recently the Beats. Books about them will never go out of style.

The author, Nino Stratchey, and her portraits, are aptly paired. After studying at Oxford University and the Courtauld Institute, she worked as a curator for the National Trust and English Heritage. She is apparently a descendant of one or more of the founding members of Bloomsbury, though neither the author herself nor her publisher have seen fit to provide a family tree or trace the lineage.

It is complicated and not easily accomplished. Still, there must be a story or two that’s worth telling. The copy on the back cover reads, “Nino Stratchey is the last member of the Stratchey family to have grown up at Sutton Court in Somerset, home of the family for more than 300 years.”

Not surprisingly, she writes about the homes and the communities where the Bloomsbury writers, artists, and thinkers lived: Ham Spray, Swallowcliffe, Knole, and Debenham House. To American ears, the names will probably sound quaint. Nino Strachey also writes about the clubs and groups the two Bloomsbury generations created and also joined: Apostles, Cranium, Memoir, and Gargoyle. The outsiders were also insiders, too.

Stratchey divides her dramatis personae, as she calls it, into two main groups: “Old Bloomsbury” and “Young Bloomsbury,” which is similar to saying “old bohemians” and “young bohemians” or “old Beat Generation writers” like Kerouac and “young Beat Generation” writers like Anne Waldman.

The members of the original Bloomsbury circle arrived in the world mostly in the 1870s and 1880s, while the members of the second circle arrived in the 1890s and early years of the 20thcentury.

The author has skin in the game. Her first book, Rooms of Their Own: Eddy Sackville-West, Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West burrowed into the Bloomsbury byways and highways. In her new book she casts a larger net and captures both eminent and also not so eminent figures like Vita Sackville-West, for example, who was for a time Virginia Woolf’s lover and the model for the protagonist in her gender bending novel Orlando.

Nino Stratchey also expresses a sense of intimacy with some of the major as well as the minor figures, including David Garnett, a book publisher and bookseller, known to friends as “Bunny,” a name he acquired in childhood.

Nino Strachey embraces the cause of those who cross-dressed and behaved flamboyantly. Apparently, Bloomsbury folk went in for “gambolling” and “frisking,” which sounds like fun. “Bisexual experimentation was the order of the day,” Strachey writes.

With a sense of indignation she adds, “they were living at a time when homosexuality was viewed by most as a disease or perversion, publishable by imprisonment.”

“Arrests in public spaces were common during this period,” she says.

As the title of her book makes abundantly clear, the focus is supposed to be on the “young.” The problem is that to get to the young, the author first has to pass through the gates of the old, and the old, including Lytton Stratchey, author of the classic Eminent Victorians (1918), are much more substantial than those who followed after them, including Stephen Tennant, an artist and illustrator.

Stratchey called Tennant “a miminy piminy little chit, entirely occupied with dressing up,” though a year-and-a-half later he changed his tune and wrote, "The poor creature was really looking extraordinarily beautiful. I quite liked him.”

In these pages the star of the Bloomsbury show is Virginia Woolf, who first shows up in the Dramatis Personae at the front of the book as Virginia Stephen, sister of Adrian Leslie Stephen, a Freudian psychoanalyst. Virginia and Leonard Woolf founded and operated the Hogarth Press and were the first to publish T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land in England.

Alas, Strachey says nothing about Eliot and very little about Ottoline Morrell, a curious figure on the fringes of Bloomsbury who nonetheless exerted an influence.

Perhaps because Stratchey builds up Virginia Woolf, she feels she has to knock her down and not accord her the honor she deserves as the author, for example, of the remarkable Three Guineas, in which she takes on Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy and also novels like To the Lighthouse, Mrs. Dalloway, A Room of One’s Own—now classics in the modernist canon. Virginia and Leonard traveled to Germany and Italy in the 1930s and saw with their own eyes the impending future for Europe.

Stratchey depicts Virginia Woolf as a gossip hound who wrote, for example, “I fell in love with Noel Coward, and he’s coming to tea.” Bully for her and bully for him. She does not go in for literary criticism, which now no longer occupies the exalted place it once did in publishing and academia.

The author of Young Bloomsbury paraphrases a notorious passage from a manuscript titled “Notes on Virginia Woolf” in which Julia Stratchey—daughter of Oliver Stratchey, elder brother of Lytton—apparently wrote that “Woolf’s novels dribbled on like diarrhea.” That’s uncalled for, especially because it goes uncontested.

In 1932 Virginia and Leonard published Julia’s novel Cheerful Weather for the Wedding at the Hogarth Press. Virginia described it as “astonishingly good—complete and sharp and individual.” Those words are missing from this book.

Strachey provides some context for the self-expression and creativity of the Bloomsbury figures. She mentions the Russian Revolution, World War I, feminism, pacifism, and socialism, but only in passing and not nearly enough. She puts most of her eggs in a basket marked “love,” and neglects a basket that might have been called “politics” or “social movements.”

In fact, her book might more accurately have been subtitled “Sex, Gender, Liberation and Creativity.”

Indeed, she has opted to focus on gender and sex rather than on pacifism, for example. In an era of LGBTQIA+ that might be an opportunistic choice in terms of publication and readership.

Who won’t find it fascinating to learn that some of the young male members of Bloomsbury—“the Oxford boys”— treated their bodies as works of art that they painted and decorated. “With cosmetics more widely available than ever before, it was all too tempting to cross the line,” Strachey aptly writes. “Lipstick, powder, rouge, and eye shadow were being mass produced.”

In light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the attacks on civilian populations, as well as major armed conflicts around the world, the Bloomsbury opposition to war deserves to be recognized, honored, and more widely known than it is.

Strachey quotes Virginia Woolf as saying, “Sex permeated our conversation. The word bugger was never far from our lips.” She does not quote Woolf on war.

An ardent pacifist as well as a committed feminist, Woolf exclaimed, “War is an abomination, a barbarity; war must be stopped.”

Pithy quotations and racy gossip exhilarate Young Bloomsbury. Readers can’t not be entertained, though discussion of Woolf’s novels and essays would have made for a far more substantial and valuable work.