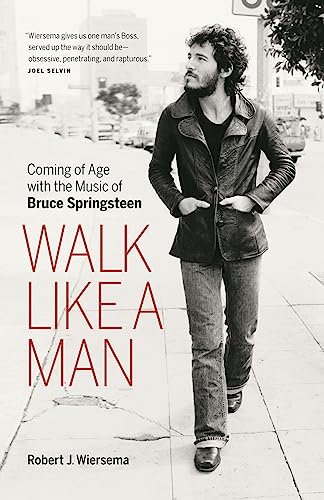

Walk Like a Man: Coming of Age with the Music of Bruce Springsteen

“I’ve strugged in the past to articulate exactly why Bruce Springsteen’s music cuts so deeply for me. Thanks to Robert Wiersema’s heartfelt book, though, I think I’m a little closer.”

In my home office, past my bookshelves and movie racks, beside my record collection and beneath the computer desk, sit seven large binders of sleeves filled with hundreds of CDs mailed from across the country. They appear in chronological order, each disc annotated by Sharpie with a date and location. The sound quality ranges from crystalline to barely audible, but untold amounts of time have been spent procuring, cataloging, and of course, listening to this music.

It’s unclear when I first got the itch to collect bootlegs of Bruce Springsteen concerts, but I do know that this obsessive-type behavior is not uncommon among his fans. It defies rationality and any prudent cost-benefit analysis, but having these shows has, in some hard-to-define way, enriched my life.

I suspect Robert Wiersema knows what I’m talking about. A bookseller and reviewer from Canada, he is also a stone Springsteen disciple, and his deeply personal book Walk Like a Man takes a noble stab at explaining quite why. It is structured primarily as a mixtape, 13 songs (plus a bonus song as performed by another band) culled from the Boss’s catalog, chosen for their relevance to the author’s life.

It is also a biography of Springsteen (the first 30 pages are an effective Cliff’s Notes rundown of his career, up to the recent death of Clarence “Big Man” Clemons) and a piece of music criticism. Each song comes prefaced with some remarks about the history of its recording and where it fits into the Springsteen canon.

These parts are informative but not illuminative; they seem like prologue to the greater project of showing how Bruce Springsteen’s music became inextricably linked to events in Mr. Wiersema’s life.

So the social misfit in “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City” will always remind the author of his own alienated adolescence in Agassiz, British Columbia.

The version of “Born to Run” that resonates most isn’t the all-familiar studio track, but an acoustic rendition performed in 1988, which he heard after bumming a ride across the border to Tacoma with a couple of drug-addled kids who left him before the show ended.

And “Thundercrack,” a freewheeling ode to a girl who loves to dance, is cemented in his memory as the song that best describes the girl who would later become his wife (“she’s got the heart of a ballerina”).

One may wonder why Mr. Wiersema merits an autobiography; certainly the experiences he describes at the various way stations of his life seem perfectly banal. “I’m as ordinary as it gets,” he writes. “A smalltown kid living in a small city, a guy with a job and a wife and son . . . I’m not famous, I’m not in recovery, I’m not bouncing back from a scandal, and I haven’t triumphed over crippling odds. I’m just a guy with a laptop and a record collection.”

But then again, given the subject, that somehow seems perfectly right— depending on how you feel about him, Springsteen’s gift/shtick has always been finding the heroic in the everyday, the extra in the ordinary (Jon Stewart put it best while honoring Springsteen at the Kennedy Center in 2009: “When you listen to Bruce’s music, you aren’t a loser; you’re a character in an epic poem . . . about losers”).

Springsteen, to his fans, has been telling a 40-year story that can be tracked alongside their own, and that’s what Wiersema’s book deftly captures. The songs stay the same, but our relationship with them evolves.

Take one of the author’s selections, “Living Proof,” a song Springsteen wrote following the birth of his first son (“Searching for a bit of God’s mercy/I found living proof”). Released in 1992, it flew under Mr. Wiersema’s radar at the time, but when his wife gave birth to their son a few years later, it took on new meaning. Here he reflects on that first moment holding his new son, whispering his name:

“There’s a photo taken that day or the next. In it, I’m holding Xander slightly away from myself, both of his feet on my chest. I’m leaning slightly from myself, enraptured, and he’s looking back, tiny and pale . . . The way the light falls on his face, the way it seems to shine back at me. It feels holy. Sacred.

“It feels like living proof.”

If you listen to the song as you read this, it’s hard to deny the emotional power of his anecdote. Unfortunately, he doesn’t always trust himself to let those stories speak for themselves, all too often undercutting his candor with distratcing, cloying footnotes.

There is no question that that Mr. Wiersema gets it. He has learned the trivia, logged the miles, and memorized the little details that comes only from years of listening to sketchy bootleg recordings (I’m glad he’s not the only one who can tell what song the band will play simply by how Springsteen counts it off)—his credentials as a Springsteen diehard are ironclad.

But will Walk Like a Man appeal to a nonbeliever? Though there’s a lot of inside baseball, at root this is a book less about the Boss or how much the author digs him than it is about the nature of fandom itself, how people can forge inexplicable connections with one artist’s work.

It’s certainly inexplicable for me—I know I’ve strugged in the past to articulate exactly why Bruce Springsteen’s music cuts so deeply for me. Thanks to Robert Wiersema’s heartfelt book, though, I think I’m a little closer.

Bruce Springsteen: Greatest Hits - Bruce Springsteen at the iTunes store