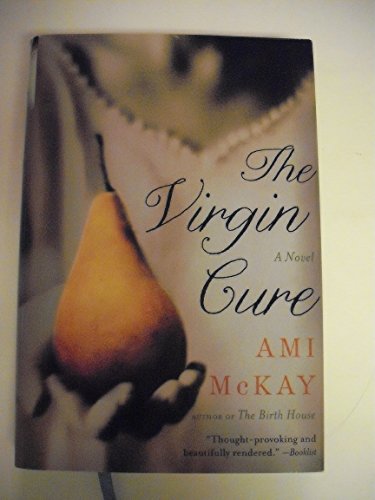

The Virgin Cure: A Novel

“. . . absorbing . . . told with elegant restraint.”

“I am Moth, a girl from the lowest part of Chrystie Street, born to a slum-house mystic and the man who broke her heart.”

So begins Ami McKay’s absorbing and occasionally distressing tale of a 12 year old battling to survive in the filthy tenements of 19th century lower Manhattan.

Neglected by a mother whose own life has been a litany of sorrows, Moth is sweetly sly, though chaste, and while urchins are easy pickings, “. . . I hadn’t given up anything to anyone yet. I hadn’t had my first blood or my first kiss . . . I understood (as most girls in my circumstances did) that I could, if careful, get quite a lot from a man . . .”

For a stroke from his rough hand across her cheek, for example, Mr. Godwin the grocer would, on occasion, give her half-a-dozen eggs instead of the three or four her mother’s pennies would buy.

Eventually sold into servitude by her mother, Moth suffers physical cruelty at the hands of her sadistic mistress that forces her to run away. Unable to return home, she’s rescued from the streets by 15-year-old “almost whore” Mae and introduced to Miss Everett, whose “Infant School” she is soon invited to join.

But Moth is no infant—and this is no regular school.

According to an article in New York’s Evening Star of October 15, 1871, such “Infant Schools” with girls as young as 11 living in them, are springing up all over Gotham City. Raised by worldly matrons, the girls are pampered and groomed until—certified “virgo intacta”—their services are sold to wealthy “gentlemen.”

In Miss Everett’s school, the wealthy clients are monitored as well. There’s no chance, insists Miss Everett, that any of her girls will fall prey to someone seeking the shocking so-called “virgin cure.”

In any case, she avers, “the notion that a man can be cured of French pox or any other disease by laying with a virgin is preposterous. And it’s nothing but a thorn in the sides of all who wish to protect young girls and raise them up right . . . I keep my girls safe.”

As does Dr. Sadie, a female physician who takes Moth under her wing as she tries to persuade her to leave the relative safety of Miss Everett’s whorehouse before it’s too late.

Despite such sensitive subject matter, this tale of Moth and her friends whose only sin—as well as only chance of escape from the mean streets—is that they are girls is told with elegant restraint.