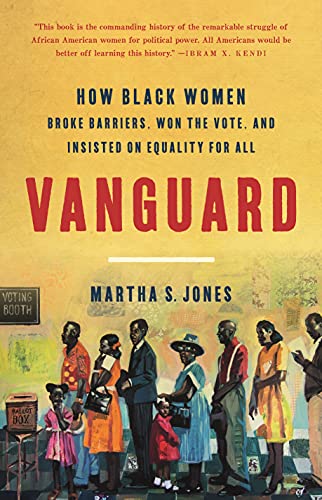

Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All

“Vanguard serves both as a tocsin and an inspiring map forward if we are to protect voting rights for all.”

“You white women here speak of rights, I speak of wrongs.”

These were the words of poet and abolitionist Mary Ellen Watkins Harper, the only Black woman to speak at the 1866 meeting of the American Equal Rights Association.

Though her audience included iconic suffragists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, no one dared talk back.

Harper is only one of the bold and charismatic suffrage leaders that author Martha S. Jones profiles in her compelling new history, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.

Jones’ book is a welcome addition to the spate of books on woman suffrage that have been published this year in honor of the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment. Through her rigorous scholarship and out-of-the-box perspective, she sheds new and important light on the crucial role of Black women in winning and ensuring the right to vote—from a time when many millions were enslaved, during the abolition and suffrage campaigns of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, through the brutality of Jim Crow, and the hard-won victories of the Civil Rights Movement.

Harper’s intrepid announcement at that meeting may have surprised the white suffrage leaders, but it was a common understanding of Black suffragists. Black women, Jones asserts, never limited their work to a single issue. “Winning the vote was one goal, but it was a companion to securing civil rights, prison reform, juvenile justice” and other political gains. “Their view was always intersectional. They could not support any movement that separated out matters of racism from sexism, at least not for long.”

This is why Jones invokes the term “Vanguard”: she explains that “despite the burdens of racism,” Black women, “blazed trails across the whole of two centuries.”

One of the most illuminating chapters begins long before the start of the mainstream suffrage movement. Maria Stewart, who at age five was “bound-out” to a Connecticut family as an indentured servant, met Black abolitionists through her church. She publicly lectured against the evils of racism, specifically addressing her call to formerly enslaved women. “Oh, ye daughters of Africa, awake! Arise!” she stated in the early 1800s. “How long shall the fair daughters of Africa be compelled to bury their minds and talents beneath a load of iron pots and kettles?”

Though their movement was contemporaneous with white suffrage campaigns and at times intersected, Black women created their own “spaces from which they began to tell their own stories of what it meant to call for women’s rights.” Formerly enslaved women had a distinct and crucial role to play. As women whose bodies had been considered to be the property of slaveholders, securing their rights “first and foremost . . . meant being liberated from the threat of rape.”

They faced many obstacles, even from erstwhile allies. The split in the national suffrage organizations over the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment convinced Black women that it was time to build their own movement. Moreover, many women drawn to organize within the African Methodist Episcopal Church, found their efforts were not always welcomed by the Black male hierarchy who considered the women “helpmeets” but not leaders.

They also faced violence. A mass antislavery meeting in Philadelphia in 1838, where Black women took leadership roles, was threatened by white mobs. A horde of vigilantes torched the Pennsylvania Hall, reducing the meeting place to rubble and ash.

Still, they persisted.

In 1895, Black women launched the National Association of Colored Women, led by Eliza Ann Gardner. The group built upon the years Black women had spent in antislavery societies, churches and civil rights organizations. United under the motto, “Lifting as We Climb,” by 1924 the organization had nearly 100,000 members across the country.

It was the height of the Jim Crow era and white supremacy was the law of the land. The Klan terrorized Black communities, hundreds of lynchings took place in public view, and no perpetrators were ever brought to justice. From the highest court in the land came the 1897 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, enshrining inequality as government policy.

Black women were very cognizant of the dangers faced by Black men when they tried to exercise their right to vote guaranteed by the Fifteenth Amendment. They faced poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses—a stipulation that a voter would have to prove that their ancestors had voted before 1867, an impossibility for any descendant of an enslaved person.

Jones describes the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment not as a guarantee of the vote, but as a clarifying moment for the battles that lay ahead.

For even after its passage, Black women were still denied the right to vote. Though they showed up in great numbers before registrars they were rebuffed and rejected. In response, a delegation of Black women called upon Alice Paul and the National Women’s Party to urge the group to work for a federal law preventing states from barring them from the ballot. But the NWP said its work was complete and closed up shop. White suffragists went on to form the League of Women Voters and to campaign for the Equal Rights Amendment, but did not address the urgent concerns of the 5.2 million Black women, 2.2 million living in the South. “Black women knew that they were being left behind,” Jones asserts. “Equality after the Nineteenth Amendment meant that Black women and men were equally disadvantaged by state laws designed to keep African Americans from the polls.”

Jones’ scholarship addresses a gaping hole in suffrage literature. She shares the experiences of many women who played a key role in American history. Though some are familiar, she sheds new light on their work. Sojourner Truth, for example, had been born enslaved—but not in the South. Truth was forced to work for a Dutch family in upstate New York—and her great oratory was spoken with a Dutch accent. Crusading journalist Ida B. Wells rebuffed Alice Paul’s instruction that she march at the back of the giant 1913 suffrage parade in Washington, D.C.—and proudly took her place at the head of the Illinois delegation.

Jones emphasizes the continuum of the struggle for voting rights by naming those who carried on the unfinished work of the early suffragists: newspaper publisher and vice-presidential candidate Charlotta Bass; Mary McLeod Bethune, appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt as head of the Office of Minority Affairs, the most highly placed Black woman in Washington; Freedom Rider Diane Nash, architect of the Selma march; Constance Baker Motley, the first Black woman federal judge; and former sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer, who defied the Dixiecrats to represent the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the Democratic National Convention in 1964.

By unearthing correspondence, articles, minutes of meetings, and other key sources, Jones provides great insight into these women’s thoughts and actions, often directly through their own words. But she also combines comprehensive historic detail with key political and social context, providing a sweeping view of American and particularly African American, history.

Jones, who holds a PhD. From Columbia University and a J.D. from CUNY School of Law, teaches at Johns Hopkins University. As a historian whose earlier books have won praise and prizes from academic and professional organizations, Jones brings her research chops to this narrative. Yet her writing style is fluid and accessible for all readers as she vividly unfolds this hidden history.

It is a bitter irony that in this year of celebrating the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, hundreds of measures are being implemented to suppress voting rights.

Currently scores of lawsuits are challenging restrictions in states from Arizona to Pennsylvania to Florida that deter and prevent people from voting—aimed at the poor, the young, the elderly, and especially African Americans.

As Jones concludes, “Our mission as historians includes excavating the past to promote well-being in our own time.” Vanguard serves both as a tocsin and an inspiring map forward if we are to protect voting rights for all.