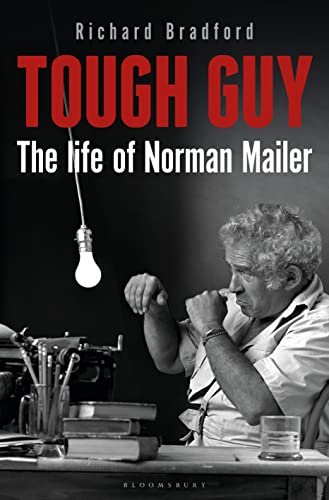

Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer

“Bradford isn’t shy in playing the role of contemptuous biographer.”

There’s an awful lot to despise about Norman Mailer—with the emphasis on “awful.” He was a raging egomaniac; misogynistic sex-obsessed six-times married compulsive womanizer; hardcore drinker who was a mean and at times violent drunk; a clueless and self-righteous advocate for a cold-blooded murderer. When his second wife Adele Morales taunted Mailer with profanity-laden aspersions on his sexuality, he stabbed her with a dirty pen knife, nearly killing Morales when the blade punctured her cardiac sac (she refused to press charges).

Mailer’s personal essays and novels were sometimes unreadable exercises in self-glorification; the movies he wrote, directed, and starred in played like amateurish vanity projects. His 1970 film Maidstone climaxed in a real and bloody mêlée between Mailer and co-star Rip Torn, with Mailer’s fourth wife Beverly Bentley and their children screaming on camera as Mailer sank his teeth into Torn’s ear, partially tearing it off. And those are just some of his unsavory highlights.

Yet despite his extensive self-created millstones, Mailer was a prolific and often brilliant writer. His debut novel The Naked and the Dead, published in 1948 when Mailer was just 25, remains one of American literature’s seminal war novels. He won two Pulitzer Prizes, a National Book Award, and was also bestowed a special National Book Award for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. Mailer served a term as president of PEN, the international human rights organization for writers. He twice ran for Mayor of New York City and co-founded the alternative weekly newspaper The Village Voice. There is no denying Mailer’s literary gifts nor his cultural impact—that is, unless you are Richard Bradford, author of the new biography Tough Guy: The Life of Norman Mailer.

Bradford isn’t shy in playing the role of contemptuous biographer. Tough Guy is put together using what might best be regarded as a redundant template for each of the book’s 282 pages. The author delivers a quick and often condescending summary of an event in Mailer’s life, follows that with scornful commentary on whatever Mailer book coincides with the biographical moment, and then moves on. And that pretty much is the whole of Tough Guy.

From the start, Bradford is dismissive of his subject’s talents. He calls Mailer’s early stories, written in that period when every young writer is experimenting and searching for a unique voice, as nothing more than the output of a peripatetic hack “looking for something he could treat as his artistic signature, a stylist or thematic exemplar that would be his alone, and he settled on what can but be described as ghoulish naturalism.”

Bradford’s sneering attitude makes for tedious, often exasperating reading. In developing what became The Naked and the Dead, Mailer relied on the many letters he wrote to Bea Silverman, his first wife, while he served in the Pacific Theater during WWII. This material was an invaluable resource for ideas, scenes, characters, and prose. It provided Mailer with solid first-hand accounts of wartime, viewed through the prism of his own unique perspective. In some sense, Mailer’s letters to Bea were early drafts for what became The Naked and the Dead. Countless writers have mined their personal correspondences and journals as a rich source for material. But Bradford dismisses Mailer’s same reworking of his old letters as nothing more than an act of cheap self-plagiarism.

Any acclaim Mailer earned is rejected by Bradford with utter disdain. He shows a special contempt for praise of The Armies of the Night—the nonfiction recounting of the 1967 march on the Pentagon, which earned Mailer both a Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. Bradford, like some kind of literary incarnation of Donald Trump, name-calls anyone who applauded the book. In Bradford’s estimation such reviewers and readers “were, like Mailer, cultural mongrels . . .” Bradford dismisses them as foolish suckers seduced by Mailer’s stylistic flourishes.

Bradford even has issues with the satirical portrayal of Adolf Hitler as Satan’s pawn in Mailer’s final book, The Castle in the Forest. With no speck of understanding nor justification Bradford rationalizes that Mailer chose Hitler as a subject “because he exhausted all other exhibitions of literary self-aggrandizement.”

Ultimately, Tough Guy comes off as part hatchet job, part poorly sourced Wikipedia entry, and part personal pettifoggery—all masquerading as thoughtful literary biography. Bradford doesn’t even bother with endnotes to back up his research. Instead, he relies on sporadic parenthetical references at the end of random sentences, listing the informational source and sometimes a page number. These are not the scrupulous citations of a professional biographer. They feel more like a lazy student’s feeble shot at MLA-style notation.

Mailer wrote thousands of pages, some good, some bad, and some with the brilliance of a master wordsmith. He could be a public monster or a private best friend, a pompous ass or erudite thinker. Often, he was a contradictory fusion of all these elements, a genuine dichotomy with an extraordinary cultural legacy. As a man and writer, Mailer was infuriating—but often deliberately so, a prankster who knew how to push all the right societal buttons for maximum effect. Better books on Mailer are plentiful, including Mailer: A Biography by Hilary Mills, Peter Manzo’s Mailer: His Life and Times, and J. Michael Lennon’s exhaustive Norman Mailer: A Double Life. Seek these out rather than waste time with Bradford’s negligible efforts.

Yet still, you get the feeling that Mailer would have enjoyed this dreary biography. Bradford’s sanctimonious approach to his subject is the exact thing Mailer delighted in lampooning. With Tough Guy Bradford gives Norman Mailer a posthumous opportunity that is sorely missed.