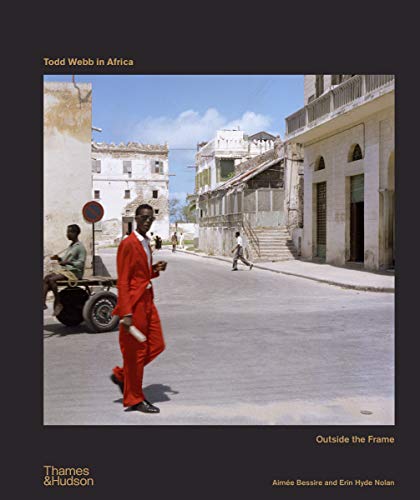

Todd Webb in Africa: Outside the Frame

"Every photo is almost a fiction or a dream,” wrote Sylvia Plachy, the longtime photographer for the Village Voice. If it's really good, it's another form of life."

In 1958 Todd Webb, famed photojournalist best known for his photographs of New York and Paris that straddled the often nebulous no man’s land between documentary and art, was sent on a five-month United Nations junket through Africa, ostensibly to document industrial progress throughout a host of countries that today largely have new names or no existence at all. He made 15,000 photographs, largely ignoring the reason for his trip. The U.N. ran 20 and left the rest on the cutting room floor.

Thames & Hudson, following up on Webb’s 2017 I See a City, has now released them in a stunningly printed, broad cross-section of the work that reveals, above all, just how good Webb was, and how much at times the work of an artist can mimic its creator. Webb’s life, for a photographer, reads surprisingly wholesome: a bank teller turned forest ranger turned auto executive, he gave it all up for the love of telling stories that, like him, seems simple but held incredible complexity on deeper viewing.

The book, published two decades after Webb’s death and in an entirely different political and cultural world from any he knew in his life, does an excellent job of avoiding the main and nearly certain pratfall any such title would fear: it is not another white man’s escapade into Africa, a leering view of perceived Black exoticism. Instead, he treats the world he found as he found it, neither pretending to be an insider nor gawking like his pith helmet had just fallen off, offering the work the same dignity and complex narratives he so routinely loaned to the streets of Montmartre or Manhattan.

Nothing is glamorous, nothing is overwrought, a series of everyday moments seen with a light touch, remembered fondly but without nostalgia. There is music here, yes, but it’s in a minor key, with no pomp or sense of special occasion. The humor is everyday humor. The drama is everyday drama.

It was made at a time of startling change on the continent, only 18 months away from the roiling revolutions of the Year of Africa, a culmination of post-war chafing at the old imperialism that had gripped the land for a century. It is easy to see why the United Nations felt little for the work, which ignores the entirety of African industrial progress to instead ask questions, the same the locals seem to have: if anything it is work that cannot decide what it wants to be portraying a continent that, at the time, was struggling to make the same decisions: is the land Muslim or Christian? Rich or poor? Is it Black, or white, or is it all technicolor?

Webb was friendly with some of the greatest lights of his generation- Ansel Adams, Georgia O’Keefe—but the fine art world doesn’t provide the same influence here as those other photographers to whom Webb is so often compared: this feels very much the world of Eugene Atget or Walker Evans, transplanted to a different time and place.

If there’s any criticism to be found here—and there always is—it’s that it feels like too large a portion of a well-made meal, with too many images that could have benefitted from a tighter edit, with large portions of the portfolio seeming to be bookended with incredible, contemplative images bookended by eight lesser pictures to break the pace of perfection.

Still, this is a lovely, lovely thing. Time, nostalgic old softie that she is, elevates the work even in its valleys, giving old images the simple grace of a world that no longer exists, if ever it existed at all. It is a work that requires patience: several viewings, different moods. What it might have lacked in brevity, it more than makes up for in style: at times, stopping with one image to unwrap layer after layer of decisive moment over thick daubs of color, it feels like jolting out of a dream, rubbing the sleep out of your eyes, to find that your waking world is the same from which you just emerged.

Plachy, it turns out, was right. If it’s really good it’s another form of life.