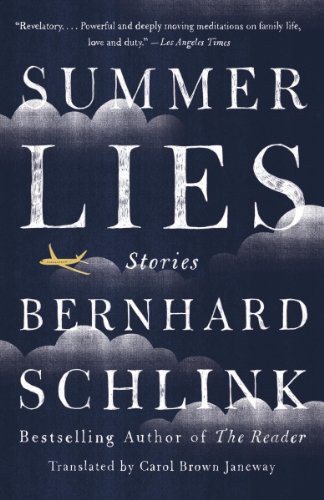

Summer Lies: Stories (Vintage International)

“. . . the life Mr. Schlink assiduously documents brims with hope.”

Whether the second word in the title of Mr. Schlink’s new story collection is meant to be noun or verb is interesting to consider.

If it’s a noun, then the warm weather equivocations of these desperate characters—always pivoting toward disaster in their own individual styles—are just that: discrete slices of life placed in each others’ company because of a shared predilection for deception. Especially self-deception and the corrective kind one generation routinely perpetrates on the next.

But if Lies is a verb, then Mr. Schlink presents a scenario far more sobering: that the bright long days of summer, teeming with color and life and intimations of deeper beauty, are themselves part of a great deceit.

When it’s a verb, summer itself is the liar—a burst of disingenuous vitality merely masking inevitable decay. And if that’s the case, these characters have little choice but to be driven to desperation by false promise. Summer always lies. Autumn proves it.

Mr. Schlink’s predominant theme is deception, just as surely as Nabokov’s was exile (not pedophilia, despite the fame of Humbert squared and his limpid, tongue-tripping nymphet). And though an unwavering commitment to a single, albeit capacious, theme may be all that the work of these two cosmopolitan, multilingual humanists has in common, the very contrast is instructive.

Whereas the great Russian-cum-American conjured with urbane subtlety and manifold sorcery a realism that remained forever subservient to his dictatorial imagination, the German delivers what feels more like straight reportage, however compassionate and interior.

And if Nabokov’s preternatural gifts for description infuse his prose with electricity that author Schlink’s lacks, it is nevertheless reasonable to contend that Mr. Schlink’s tales are not altogether poorer for the lack of voltage.

In their fashion, Mr. Schlink’s sepia-toned tableaux—as much grunt and groan as coloratura—restlessly stake out plain truth—at least as that elusive beast is more commonly (and dimly) perceived by the rest of us non-Nabokovs.

His stories and characters writhe within a familiar, recognizable world—and it’s the universality of the emotions he explores there that give the work its occasional, undeniable power.

The seven stories in Summer Lies, the author’s first story collection to appear in English since 2001’s Flights of Love, are not happy ones. (Nor, for that matter, were those in its more optimistically titled predecessor.)

In the collection’s moving, atmospheric opener, “After the Season,” a young-ish musician in a rain-soaked beach town falls in love—quickly, entirely, preposterously—only to let the intimidating wealth of his newly beloved annihilate his emotion. Or perhaps the woman’s riches are just an excuse.

Mr. Schlink, whose best pages practically pantomime consciousness, doesn’t wrap up life (or thought) in neat parcels. He follows it where it leads.

The amorous musician can’t shed his old life, his old self—a necessary molting. Even as he imagines a future filled with passion and happiness, the idyll is ever annexed by fear, spooked by imperfections—like a rainy vacation. We learn near the end that “he had decided. He would give up his old life and start a new one with Susan. As soon as he could begin it properly.”

Ah, properly. There’s the rub. Mr. Schlink’s characters don’t have old lives and new lives but one life, one self. And it persists, doggedly like our own.

In “Johann Sebastian Bach on Ruegen”—worth the price of admission for the lovely disquisitions on Bach alone—we learn that the protagonist “would have liked to cry, not just at happy endings in the movie theater but also when he was overcome with sadness about the end of his marriage or the death of his friend or simply the loss of his life’s hopes and dreams.”

Mr. Schlink’s deftly monitors how resentments build up in this man’s mind like so much plaque in the arteries, until he experiences a revelation like a bypass, though less sustaining.

In “Stranger in the Night” the narrator’s seatmate, who happens to be on the lam, confesses a shocking crime, casually spinning a tremendous tale of international intrigue in which the truth plays hide-and-seek and sympathies are masterfully played upon. The flight they’re on turns dangerous and, in lines that could find a place in almost any of these stories, the confessor admits, “I used to think that people who don’t have long to live tell the truth. But perhaps people who don’t have long to live are the worst liars.” Nobody having so long to live, perhaps Lies is a verb after all.

Not every story hits the same high marks. While Mr. Schlink is a virtuoso of the aggrieved mind, sometimes the deliberate pantomime of consciousness is too successful.

A story like “House in the Forest,” with its evocative fairy tale title, employs desultory prose and a tedious pace to virtually mirror the slow self-strangulation of an obsessive’s thinking.

As art, the story nobly ventures to match technique to subject. But the venture is fraught, for the reader, with an unhappy fact: obsessives are, almost without exception, boring and ludicrous.

Yet there remains, even during this frustrating exercise in verisimilitude, a strong desire to see what will happen next—a desire common throughout these pages.

However shadowed, the life Mr. Schlink assiduously documents brims with hope. If it didn’t, the tantalizing tortures his characters suffer as they strive for their brass rings, their happiness, their answers, wouldn’t be so stark, sorrowful and moving.

Be it a simple existence in the country, a heart-to-heart with Dad, or any meaningful congress with the world—their quests bring to mind Heidegger’s truism that “longing is the agony of the nearness of the distant.”

In other words, it’s deceivingly close and infinitely far away—like every exile’s home.