Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory

Janet Malcolm died last year, and her passing was profiled in over 40,000 obituaries online. She left behind a huge entourage of fans who had spent decades immersed in her literary nonfiction. Most spoke about her piercing prose which accompanied an ongoing tension that lay at the center of her work. Some said she could be occasionally merciless. Those she interviewed often felt intimidated by her heightened attention: the way she noticed they ate, or cut a tomato, or decorated their apartment, or what clothes they wore. She once described photographer Richard Avedon’s work as representative of “photography’s capacity for cruelty.”

She wrote about psychoanalysis and its practitioners, journalism, the deficiencies of the American justice system, the art of biography, photography, and the legal battles that erupted in our courts. She claimed to always be on the lookout for fraudulence; paying specific attention to what was left unsaid. She was one of a kind.

Many of her journalistic colleagues were insulted by her insinuation that all narrations were distorted by the reporter’s bias. Despite the obvious truth in this proclamation, they felt she was denigrating their profession. When an adoring young writer Katie Roiphe interviewed Malcom for the Paris Review, she was taken aback by Malcolm’s controlling ways. Malcolm insisted all questions be sent to her via email and she would respond in kind.

No one who spent the last decades reading her penetrating work in the pages of The New Yorker or one of her many groundbreaking books such as The Journalist and the Murderer, or In the Freud Archives, could dispute her extraordinary ability to impress us with her fearless intelligence and creative brilliance. She said writing was always difficult for her and how it took her a long time to polish her prose into the provocative pieces they became.

When she came to writing her autobiography, her imaginative juices dried up. She wrote about the experience in a blog post: “I see that my journalist’s habits have inhibited my self-love. . . . Not only have I failed to make my young self as interesting as the strangers I’ve written about but I have withheld my childhood.”

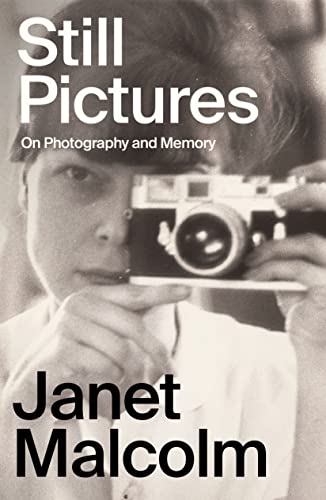

She tried again years later and the result is this new work published posthumously called Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory. Instead of trying to write a traditional memoir, she decided to choose a random group of childhood photographs and respond to them viscerally allowing her mind leeway to travel wherever it pleased. The result is a strangely heartbreaking reminiscence of her young life that Malcolm had tucked neatly away somewhere awaiting excavation. The usually brazen journalist seems intimidated by her past; perhaps thinking it held the power to wound her. She often dances right up to the line of major reckonings, but before she arrives, she shyly walks off the stage. It is her vulnerability that dominates throughout these pages, and we get a peek at a Malcolm we haven’t seen before.

Malcolm came to New York in 1939 with her parents and younger sister when she was only five. She was born Jana Klara Wienerova, and her escape from the Nazis was on one of the last trains leaving Prague. Malcolm still seems unable to come to terms with the enormous gravity of her departure, or the subsequent rupture it had on her entire family. Her father was a neurologist and psychiatrist and set up a medical practice in Yorkville, Manhattan that was filled with Czechoslovakian refugees.

Malcolm struggled in school at first, but once she mastered English, her grades improved. Back home in Czechoslovakia, her parents had been completely secularized nationalistic Jews who identified solely as proud Czechs. Malcolm claims she didn’t know she was Jewish until she came to America and started uttering Jewish slurs until her parents informed her about her identity. Instead of prompting additional inquiries, Malcolm seems to have shied away from this charged topic, and never wrote at length about her Jewish identity, Israel, the Holocaust, or anti-Semitism. It feels like an inexplicable omission.

One of the first images we see is a young Janet Malcolm, about three, sitting on a stoop and looking impishly lighthearted. Malcolm writes “The child in the snapshot is me. I know nothing about where or when the picture was taken. The sunsuit speaks of summer vacation, and I am guessing at my age. I say ‘my’ age, but I don’t think of the child as me.”

She repeatedly is at a loss to remember anything about many of the photographs she looks at, and the reader wonders if her forgetfulness is a survival tactic developed long ago. She does recall a first vivid memory. It is a beautiful country day and there is a procession of little girls in white dresses carrying baskets with rose petals that they are tossing to the ground. She wants to join them. An aunt gives her a basket filled with peonies and she remembers being stung by indignation that her basket did not carry the precious rose petals which clearly were the more cherished flower. She recalls feeling insulted and resentful “that I had not been given the real thing, but something counterfeit.” This feeling of unworthiness seems to have smoldered beneath Malcolm’s sturdy exterior. She cites other events where she felt somehow less that then others. She worried in school that she was not liked by her classmates. Later on, when she had romantic crushes, they were often not returned.

It surprises her that she remembers the journey to America. That she had a boil on her arm that had to be lanced. And that a certain dress her mother wore that she always adored was suddenly missing from her luggage; something that bothered her for reasons she could not fathom.

She recalls elementary school in Yorkville and being ashamed when her mother came to assemblies dressed in drab garb unlike the other mothers who wore sunny frocks. She remembers a certain tension between her parents that seemed to stem from her father’s poor origins and her mother’s upper-class roots. About her father, she writes with the most uninhibited tenderness praising his gentleness. She concedes there were areas of contention between them, but tells us she does not wish to reveal them to us. She seems peeved at his self-absorption; he was a man in love with so many things in the world.

About her mother, she is more forthright. She speaks about her mother’s neediness and growing depression as she aged, and how hard it was for her as a young woman trying to break away from home. She tells us about her mother’s capacity to charm others, and how she saw this attempt to please others incessantly as a sign of weakness she did not wish to emulate.

Her mother was plagued by headaches, indigestion, constipation, muscle pain, and increasing mood turbulence. Malcolm seems to have survived her neediness by erecting a wall of self-containment around her that blocked her from the full force of her mother’s pain. We are taken aback when she describes how her mother, when she wasn’t ravaged by depression, had an “exuberance and vivacity and warmth,” which Malcolm felt was “a kind of front for an inner deadness of spirit.”

We get the sense that Malcolm has the same numbness but is able to channel hers into productivity. But still, it is hard to imagine Malcolm overwhelmed by any of the ecstasies of life; either love or romance; or the joys of family; or the exuberance that comes sometimes from just being alive. There is a certain steadiness about her that seems too tightly wound, perhaps suppressing the wreckage that lay beneath it.

Malcolm’s first marriage to Donald Malcolm ended in divorce. They had one child, a daughter whom Malcolm does not discuss here. Her second husband, Gardner Botsford, was an editor at The New Yorker, and their collaboration on her long pieces is legendary. Their relationship began with an adulterous affair, and while it is unusual for Malcolm to be so forthcoming, she says little about their relationship other than her dependence on him for shaping her work into finished prose. He died in 2004.

Malcolm seems to know she is leaving us hanging and admits “The fear of speaking from the heart is deep-seated. We form the habit of defending ourselves against rejection early on.” She adds “I would rather flunk a writing test than expose the pathetic secrets of my heart. The prerogative of cowardly withholding is precious to the most self-revealing of writers. . . .”

Malcolm maintains memories are fluid and often morph over time. Sometimes our memories get short-circuited, and we think things happened that never did. Or possibly happened much later on. Some of the more delightful passages here are her lighter reflections. She recalls an afternoon with a middle school friend with whom she went for a milkshake after school, and can still hear her buddy saying “It tastes so good” over and over again.

Malcolm’s strong suit isn’t confession or revelation or even seeking redemption. Her natural inclination is a suspiciousness of the past. She seems immune to regret except in the rarest of circumstances. It is impossible to read this work and not feel a little sorry for her. By so many accounts, her life was a masterwork of self-invention. But some readers may find themselves thinking there is much she missed out on. Such are the infinite mysteries of an individual human life.