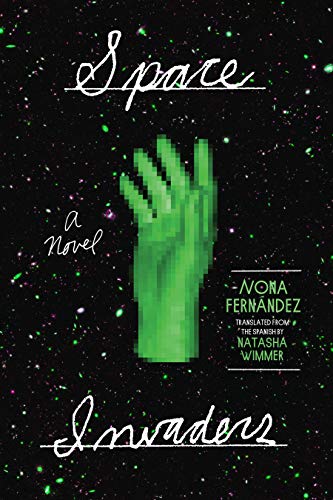

Space Invaders: A Novel

Space Invaders is a novella, barely 66 pages, each one only seven-by-five inches, that effectively holds between its covers a story extending far beyond the physical space it might occupy on a bookshelf.

It’s a convincing depiction of totalitarianism made all the more chilling because author Nona Fernandez refrains from needless overdramatization, instead using the everydayness of surprise—what was there before, what is now no longer, what is lost, what disappears silently—to show how the crime of political oppression is internalized, day by day, by the collective: the people being slowly brutalized and dehumanized.

“Time isn’t straightforward, it mixes everything up, shuffles the dead, merges them, separates them out again, advances backward, retreats in reverse, spins like a merry-go-round, like a tiny wheel in a laboratory cage, and traps us in funerals and marches and detentions, leaving us with no assurance of continuity or escape. Whether we were there or not is no longer clear. Whether we took part in it all or not isn’t either. But we’re left with traces of the dream, like the vestiges of a doomed naval battle. We wake up with smudges of cork beard on our pillows and with the unpleasant feeling of having been assailed by green glow-in-the-dark bullets, by a wooden orthopedic hand.”

Using memory as a fictional tool to full effect, she shows how the outcomes of fascism overrun history’s bookends, the dates on a calendar an inadequate bracket for containing the consequences on the people it serves to subjugate, each scene here reaching far back into the past, and also far into the slow-moving march forward that is a future in which every life’s present is now dictated by a state turned enemy.

“Maldonado dreams of the word degollados. She sees it printed in the headlines of every newspaper from back then. Caso Degollados. Throats slashed. In newsstands, on the dining room table at home, in her mother’s hands, in the fat binder on shelf number four in the third aisle of the school library. Maldonado doesn’t know what degollados means, but she senses that it’s something awful and then her dream turns into a nightmare.”

The country Nona Fernandez shows us in Space Invaders is 20th century Chile, and it is fitting that the story is told through memory: eight adults, former classmates, remember Estrella Fernández, a girl who attended school with them when their worlds began to change. A forlorn girl, a lonely girl with a military father who disappears one day without a word, no goodbye letter like the ones she had been in the habit of sending to them before she disappeared, even though she saw them at school every day, signed with a star because Estrella means star in Spanish, these letters now remembered and romanticized in all their heartbreaking innocence and emotion by the friends from whose memories she’s fading, if slowly, painfully.

“Riquelme never went back to González’s house. The thought of those orthopedic hands terrified him. The few times he and González were partners on an assignment, he would invite her to his apartment, where hands didn’t come off bodies and children didn’t hang on the wall. The rumor spread around the school like a kind of myth, and no one, absolutely no one, dared to go over to her house for fear of Don González’s spare hands. Not even Maldonado, who exchanged letters with González, and who claimed to be her best friend.”

It is also fitting that the narrators (the point of view always appears to be plural even when only one speaks, another fabulous fiction trick from Fernandez) are telling the tale from childhood’s vantage point, because Space Invaders is certainly a story about the loss of innocence in the face of betrayal by a savior, something not often addressed, but certainly an important part of the pattern that the history of totalitarian regimes suggest, all seeming to arrive in the midst of rightful discontent, cloaked in the costume of justice for the downtrodden, propped by the idea of a moral uprising, championed by those most disenfranchised (and conveniently aided by a few well-placed opportunists), by the most angry at the country that seems to leave them behind, only too late discovering they have helped usher in a doom much worse than they rose against.

That this difficult subtext is captured here with such depth and lucidity makes it a work worthy of being studied as part of the canon of tales—Animal Farm by George Orwell, The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles, The Feast of the Goat by Mario Vargas Llosa, and even The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins—that appear prescient, but are only just effective at showing the consistent predictability of fascist regimes.

But all is not history here. There is a wonderful fogginess to Fernandez’s gorgeous prose, in this novella translated faultlessly by Natasha Wimmer, whose experience translating the works of Roberto Bolaño and understanding of Latin America’s traumatic history with dictatorships aid her in rendering clarity without removing the elements that help Space Invaders do so much, so quickly: the feeling of dread, the anxiety of the unknown, the arbitrariness of new rules unspoken as the children try to make sense of their lives and their roles in a newly repressive society, their childhoods forever twisted, but also united, by the events around them, their young minds incapable of refraining from turning even the most violent cruelty into a game about the invasion of space.