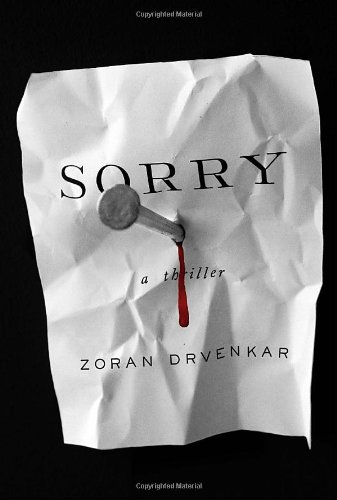

Sorry: A Thriller

“Sorry has all the ingredients to make it a compulsive read. It’s slick, chock full of twists and turns, and dripping with narrative thrust and intrigue. . . . By addressing his villain as ‘you,’ author Drvenkar inspires empathy where usually there would be none. From the darkness, he tries to find some kind of light.”

Sorry is a highly original, modern crime thriller set in Berlin, Germany. It’s a novel exploring the darker side of the street, poking its narrative nose into those locations where the illumination from the street-lights just won’t reach. It’s a book set within the treacly dark margins of society, exploring notions of control and freedom, memory and shame, guilt and atonement, revenge and forgiveness. Mostly, it is a story of victimhood and abuse. Zoran Drvenkar’s unflinching study of the "cycle of abuse” is excellently and movingly wrought.

Sorry has all the ingredients to make it a compulsive read. It’s slick, chock full of twists and turns, and dripping with narrative thrust and intrigue. We’re sickened by the darkness of the world the characters are compelled to inhabit, and yet we want to know more about it. Like John Connolly’s Charlie Parker novels, this exploration of “sick people who destroy souls” both attracts and repels.

“Being in darkness while everyone else was in the light. Being helpless, defenseless. Being furious and not showing it. Alone in society. Constantly hungry, thirsty, weary, exhausted. Feeling the life around him and not being able to touch it. [. . .] Traveling on a different track. Far away. Invisible.”

But what sets this work apart from the large swathes of crime thrillers which hit the shelves every week is the language. Like Connolly, Mr. Drvenkar manages to find a murky kind of poetry in the shadows, and the shifts in narrative perspective make for a highly unsettling experience for the reader.

The opening section of Sorry is told from a second-person perspective. We’re used to second-person narration from song lyrics, from love ballads, but right from the first line here, we’re shunted right out of our comfort zone: “You’re surprised how easy it is to track her down.” Immediately, we’re drawn in. Immediately, we’re made to feel somehow complicit.

Throughout the story that follows, Mr. Drvenkar subtly plays with our expectations. This certainly doesn’t read like a common or garden crime-thriller: “You’ll now be wondering why we are spending any time on a woman who can’t even manage to wash her face or put on fresh clothes after she wakes up.”

Or: “We’re approaching the start. You are now ready for the present and know who’s going to be crossing your path.” And: And “It’s time for you to enter this story. Through a back door. Like a ghost rising out of the floor and taking the stage.”

The “you” character is present throughout the story but we can never quite meet “your” eyes. This development of the villain as just off the page, just out of our grasp, “a blur [. . .] a mirage that could dissolve into nothing at any moment,” is finely contrived by Mr. Drvenkar. It goes straight to the heart of the text; it shows the simultaneous presence and absence of this shadowy figure that has been ground into a husk by the abuse that has been meted out to him. Abuse that has made him unable to look himself in the mirror: “Even though you were paying tribute, your condition didn’t improve. Your eyes kept avoiding you. You cried, you hit the mirror until shards fell into the sink. Nothing helped.”

The significance of mirrors, of being able to look oneself in the eye, is crucial to the narrative. Guilt and shame haunt many of the characters. The desire to make amends, or to gain vengeance, forms the thrust that drives this story forwards until it reaches its terrifying climax.

As a counterpoint to “you” we’re presented with four childhood friends who are bumbling through their twenties without really making much of an impact upon life. Until one of them has a moneymaking idea which will change them forever.

Kris, his brother Wolf, Tamara and Frauke form an agency, named Sorry, which will conduct the dirty work of apologizing (“at a damned good price.”). And the orders begin to roll in. From corporate clients, businessmen who are keen to say sorry for making people redundant, or for breaking off affairs, as the four observe, “Everything starts with a lie and ends with an apology . . .”

But when they are called in to a flat to apologize to a woman and find her dead body, everything lurches out of their control. The woman has been nailed to the wall; one nail has been hammered directly through her skull. (Mr. Drvenkar’s description of this is perhaps the most sickeningly visceral in the entire novel: “You drive the nail through the bone of her forehead. It takes you four more blows than the hands did, before the nail pierces the back of her head and enters the wall. [. . .] You wait and study the elegance with which the thread of blood moves over her face. [. . .] It’s fine, you don’t have to correct anything, everything is right.”)

Because the four friends are already caught in a web, they are forced to dispose of the body. Mr. Drvenkar relishes in the details: “In the DIY superstore they buy buckets and cleaning materials, a pair of pliers, trash bags, spatulas, and a black plastic tarpaulin. They put a flashlight and three spades in the shopping cart, so that the handles stick out like palisades.” And: “They ram their spades into the earth, press them in hard with their heels, furious with death.”

Quickly, the four become embroiled in a dangerous game that has far more players than they’d previously anticipated. But at the heart remains “you.” “The mystery is like a house with walled-up windows and only one locked door. There’s only one way into the house,” and “you” are the key.

Eventually, we start to learn something of “your” backstory. The abuse that has been smashed into “you” in childhood, when “you” and your best friend played at Butch and Sundance.

Back then, “they thought life was fair. They believed in equilibrium, and the good guys winning in the end and the bad guys losing mercilessly and shamefully. You’re aware that life is anything but equilibrium. It’s the purest chaos. darkness lurks behind every door. Shadows live behind every window.”

Of the abuse, only a “single sentence was ever uttered.” And, “That sentence still resounds for you like an unpleasantly high note that summons up all the memories at once. Even though it only ever left Butch’s mouth in a whisper, it held more power than a scream. ‘I never want to be a dog again.’”

And throughout the novel, the moral question remains unanswered. One character contends that there are people “who do not deserve forgiveness.”

Mr. Drvenkar provides no answers, but what’s important is the fact he raises the question. By addressing his villain as “you,” he inspires empathy where usually there would be none. From the darkness, Zoran Drvenkar tries to find some kind of light.