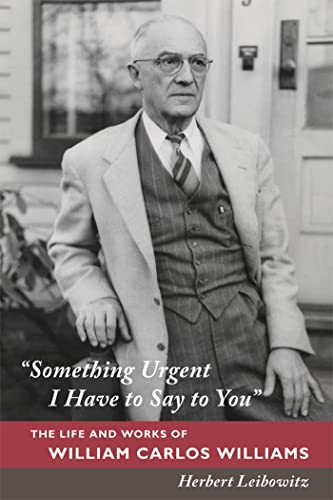

Something Urgent I Have to Say to You: The Life and Works of William Carlos Williams

“Biographies are but the clothes and buttons of the man. The biography of the man himself cannot be written.”

—Mark Twain, Autobiography, 1924

Mark Twain had it right. Biography is nothing if not a tricky genre–where the clothes and buttons of a person’s life are cut, tailored, and assembled into a biographer’s specific narrative. Early 20th century American doctor-poet William Carlos Williams had a particular skepticism to having his own biography written, concerned that his life—his hopes, his ambitions, and his accomplishments—would be twisted and turned completely out of context and his place in American poetry would be lost within his surrounding Modernist milieu.

In Something Urgent I Have to Say to You: The Life and Words of William Carlos Williams, Herbert Leibowitz considers Williams’s concern about an accurate and appropriate biography, immediately lending a particular empathy toward his subject and fellow writer. In a brilliant and compelling twist of source, Mr. Leibowitz lets Williams tell his own life story through his poetry, letters, essays, and critiques. The reader quickly comes to appreciate Williams’s fantastic intellectual context as he and his poetry moved in the glittering circles of early 20th century Modernism and Imagism—in both America and Europe.

In using Williams’s own poems and writings as a primary source for his biography, there must be, by necessity, a careful balancing of supportive detail and literary analysis to avoid a self-reinforcing narrative. Mr. Leibowitz’s manages to successfully strike that balance in a way that illustrates the complexities of Williams’s life and work without slipping into a Freudian-esque reassessment of Williams’ life and motivations.

Mr. Leibowitz explores a particularly intriguing aspect of Williams’s life, drawing on the displaced, unappreciated relationship that William Carlos Williams had with his wife, Florence (“Flossie”). To that end, the reader walks away with a bit of Flossie’s biography as her “clothes and buttons” are carefully described, illustrating the crucial role she played in Williams’s many successes and how Williams, repetitively and unendingly, undervalued her. The complexity of their decades-long relationship is put before the reader through lines of Williams’s poem, “Kora in Hell” (published in 1920), juxtaposed with the years of logistical support Florence lent to Williams’s literary and medical careers.

Most interesting, however, is the case Mr. Leibowitz builds throughout Something Urgent I Have to Say to You about the uniquely enigmatic voice that Williams wanted to bring to American poetry. Through the wide distribution of critical responses to Williams’s poetry when published, the modern reader understands how Williams saw himself: as an educated doctor outside of everyday America but also an outsider to the literary circles of madcap Modernism. Williams tried to belong to both worlds. yet neither accepted him and his viscerally-real American poetry in the way Williams wanted. Williams’s poetry shows a poignantly raw and very physical side of American life, giving voice and vision and, perhaps, a sense of pragmatism, to an “America” that eluded most of his contemporaries like Ezra Pound.

By highlighting Williams’s dual careers, as doctor and writer, Mr. Leibowitz’s brings an interesting angle to the early 20th century literary scene, where the literary intelligentsia were chock-full of writings from T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound. While Williams is not quite sounding his “barbaric yawp” Whitman-style from the rooftops of his hometown of Rutherford, New Jersey, his is, nevertheless asking his readers to re-evaluate the concept of American voice, idiom, and the very concept of American poetry.

As such, Williams’s life and poems provide an interesting break from the rather dilettante poetic tradition and the reader appreciates that Williams’s poetic pragmatism seems to stem two things. First, he brings a particular sympathy to his New Colossus-like crowds of patients, drawing on his heart-rending experiences as a doctor for the huddled, tired immigrant masses of New Jersey. The second interesting break with his literary contemporaries is his frustration with, what he saw, to be the generally scholastic nature of American poetry—poetry that constantly looked to Europe and the Ancient Classics for validation and allusion.

If writing biography is tricky, then writing good biography is even more fickle. In Something Urgent I Have to Say to You: The Life and Works of William Carlos Williams, Mr. Leibowitz, however, crafts a fantastic biography of one of the most complex and interesting early 20th century American poets. Using Williams’s own writings as a way of reinforcing part of the biography serves to familiarize the reader, more, with Williams’s writing and his voice, but also serves to alleviate Williams’s own concern about the nature of biography.

“Life,” as William Carlos Williams wrote, “Life is a flower when it / opens you will / look trembling into it unsure.”