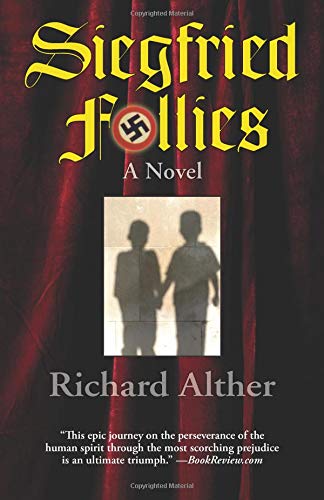

Siegfried Follies

The edition of Siegfried Follies by Richard Alther that this reviewer recently read could use a thorough revision.

Suppose the two eight year-old boys, one German and the other Jewish, in author John Boyne’s The Boy in Striped Pajamas, were not murdered in a concentration camp gas chamber, but rather managed to survive World War II and the Holocaust as orphans, later building a post-war life together. That is more or less Siegfried Follies’ narrative starting point.

The strategy of pairing a majority culture character with a minority character to show the latter’s humanity is at least as old as Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Without digressing into the debate as to whether Twain’s Jim is a fully developed character who demonstrates his humanity or simply a two-dimensional racial stereotype, in the case of Siegfried Follies the extroverted, resourceful German character, Franz, is a more successfully realized character than his introverted, clinically depressed, Jewish friend J.

That the latter’s name is only an initial might make readers wonder whether or not the failure to fully develop the character is intentional. The book’s title, Siegfried Follies, refers to Siegfried, the wounded hero of German folklore, and both its protagonists are emotionally wounded.

Maybe to avoid an implied equivalence between the suffering of wartime German civilians and that of Jewish genocide victims and survivors, J’s emotional wounds are more pronounced than Franz’s. On the other hand, when the adult J thinks “of all his Jewish communities, one as in-turned and atrophied as the next” Jewish readers may wonder whether they are to take this as evidence of internalized self-hatred or if that is what the author really thinks of them.

The second word of the title, Follies, refers to a burlesque show; if the title implies a connection between the characters’ childhood emotional trauma and their adult sex lives the text provides insufficient evidence of such causality. Perhaps the word Follies refers simply to light entertainment.

Franz is an eight- or nine-year-old German orphan and Hitler Youth member who works in a Munich maternity hospital during the last year of the Second World War. He has no memory of his birth parents and only a vague recollection of his most recent foster parents.

The hospital represents the Nazi regime in microcosm: its posters, programming, and public address announcements reaffirm the racist and racially chauvinist ideology Franz has already been exposed to in the Hitler Youth, and its administration mirrors the country’s ruthless, despotic, and authoritarian government. Patients and staff who are insufficiently obedient and ideologically compliant as well as disabled or racially “undesirable children” are murdered and their bodies disposed of as garbage.

Franz’s supervisor is a nurse who recruits him to deliver embezzled food and supplies to her apartment some blocks away. On such a trip Franz passes a railroad track where he sees a boy his own age thrown from a train clutching a violin case. He takes the injured, malnourished boy—who appears to be mute and to have suffered amnesia—back to the hospital, cleans him, hides him and his violin in his room, and begins to nurse him back to health. The child’s only identification is a tattoo on his arm with the letter “J” from which Franz infers that the boy is Jewish. Since the boy cannot recall his own name Franz calls him J.

At war’s end Franz and J, who now can speak, leave the hospital, and it soon becomes clear that Franz has natural business acumen and that J, whom Alther describes as a brooder with searching eyes, is more academically gifted. Franz finds work in a variety of enterprises and with his earnings rents an apartment and supports J who attends an elite school. Readers may wonder how, between the ages of nine and seventeen, the pair remained off the radar of Munich’s and the Federal Republic’s child protective services and foster-care system; for instance, whom did J list as his guardian when he enrolled at the school? J summarizes his reading and lessons for Franz who delights in food shopping and cooking for J.

Franz also has a keen eye for home furnishings and interior design. When he develops a silk and satin fetish and introduces J to mutual masturbation this reader wondered if the pair would become a gay couple as adults, but first Franz and later J discover they enjoy sex with women. Nonetheless their male bond has an erotic though unconsummated undertone. Franz’s homophobic language reminds readers of how ubiquitous sexual bigotry once was, but taken in context, the lady dost protest too much.

After living together for eight years, J graduates from the Goethe Gymnasium and is admitted to Heidelberg University (like an earlier brooder, Prince Hamlet). J decides not to attend university but instead to immigrate to Israel and join a kibbutz.

On learning of J’s decision Frank decides to also make a new start and plans to immigrate to the United States, where he changes his name and works for a cleaning products corporation headquartered in the fictional city Buena Vista, Indiana.

When we next meet J he has intentionally misplaced Franz’s U.S. address and calls himself “Yud” (here spelled “Yod”), the Hebrew letter that corresponds to I, Y, and in German, J. Alert polyglot readers will notice that the pronunciation of the name of the Hebrew letter in question resembles that of the first syllable of the German word for Jew, Juden.

This Israeli chapter would have benefited from geographical and demographic fact-checking by someone who has actually lived in Israel and is familiar with Israeli and Jewish history. On a trip to Jerusalem Yod views the city’s landmarks from its outskirts, including the Dome of the Rock, but in the 1950s Jerusalem was a divided city, and the Dome of the Rock was in Jordanian east Jerusalem and not visible from street level from most parts of Israeli west Jerusalem and certainly not from its western approach, at the time the only direction from which Israelis could reach their capitol. Another section of the same chapter refers to swarthy Sephardic Jews from Barcelona, but Israel’s Sephardic Jews are more likely to come from North Africa or the Balkans than Spain, whose Jews were expelled in 1492. Jews who found refuge from Hitler in Spain under Franco were mostly Ashkenazi Jews.

Jewish characters created by Gentile writers such as George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda and John Updike’s Henry Bech are complex and credible, but the same cannot be said of J/Yod/Jay in Siegfried Follies. Franz/Frank and Marcy are more fully developed characters, but this novel is like a stool with one short leg. An underdeveloped key character combined with a contrived plot equals a disappointing read.