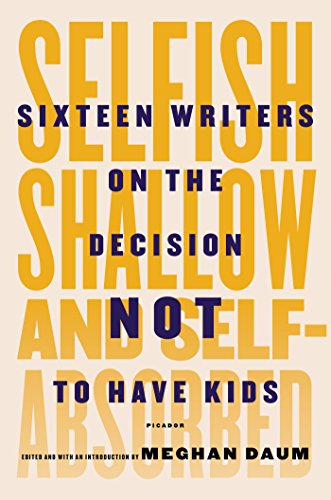

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision NOT to Have Kids

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed is a timely book for the discussion in current culture about the decision on not having kids. These authors have purposely decided not to have children rather than not being able to have children, which is a separate topic. Meghan Daum has gathered 16 fantastic essays from men and women, mostly women, who talk about their lives and their decisions. Some of the contributors adore children and others abhor them, some are happy being aunts or uncles and others would rather stick to pets. Some authors talk about their art and craft coming first and buy into the idea that they would have to pick one or the other (the other being children).

The various authors who have contributed to this fantastic volume each weigh in on the choice of not having kids, something which is still culturally looked at with suspicion. Much as the title suggests, the accusations flung at those who choose not to have children range from accusations of selfishishness, shallowness, or self-absorption—when perhaps the opposite is true.

While it has become more acceptable to have discussions of childlessness by choice in popular culture, there is still a stigma attached. Those authors who have contributed to this discussion are not millennials or necessarily Gen-Xers but Baby Boomers who lived through intensely patriarchal, gender-biased, and proscribed cultural periods in which such a decision was entirely unthinkable, and surely indicated something was wrong with the person. It is refreshing to read about older adults, those in their 50s and up, and those potentially older to see that their lives are not abysmal failures or plagued with deep regrets regarding not procreating.

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed is not a diatribe against “breeders” or a condemnation of procreation. This volume is an earnest discussion about choices made. Some authors wanted to want to have children, others even tried then decided against trying again after miscarriages and mishaps. Some authors came from damaged childhoods and others had the average family. Some authors feel quite strongly that childlessness is a must if an individual wishes to experience life and remain an individual, and others buy into the possibility of “having it all” yet simply chose not to have children for perhaps genetic reasons.

It would have been nice if author Daum had included more male perspectives, but that there were any at all was particularly refreshing. Also, it would have been fantastic to include the perspectives of non-writers in order to get a wider gamut of those women and men who make such decisions. Many of the writers do consider their craft in relationship to the decision they made.

Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed does not read like a negative feminist manifesto, a rant against the patriarchy, or an elevation of the womb to Madonna status, but rather as a collection of intelligent people who are sharing, albeit somewhat guardedly, their private lives with readers. Putting the cards on the table of what their lives are like having made one particular choice. Of course, there is no real way to determine what would have happened had these individuals chosen to have kids or had the opportunity to do so—that would constitute pointless conjecture.

This book is a commendable collection of essays for people who want to hear from other like-minded individuals on the issue, for those who are in the midst of deciding one way or the other, or those who perhaps want to understand the reasoning from the other side.