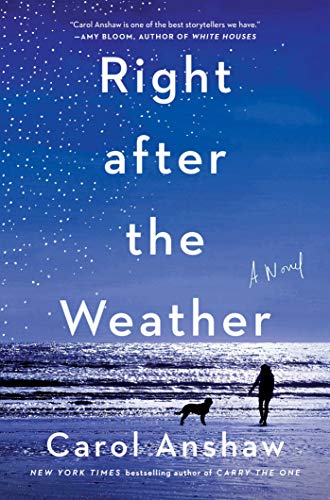

Right after the Weather

“In this exquisitely written, psychologically sophisticated novel, rich in insight and sensitivity to human vulnerability, Anshaw suggests that shared tragedies do not necessarily draw human beings closer.”

Carol Anshaw has followed her New York Times Notable Book and bestseller, Carry the One, with Right after the Weather, her fifth novel, and in it she has again demonstrated her prodigious capacity for emotionally complex characters drawn with economical, point-on diction replete with wry humor, wrenching pain, and utter loveliness.

The story is set in the context of a political storm, the American national election in 2016, by giving it a timeline that begins in October of that year and ends in March 2017. For many, that turbulent weather represented a before and after delineation, much the way people might mark time by remarking that something occurred before or after a destructive hurricane. Indeed, Anshaw’s characters perceive the election to have marked that sort of destructive change.

The novel opens with the sense of coming emotional weather also: Cate, a lesbian in her early forties, has Graham, her sweet but more than a little paranoid ex-husband, hiding out in the guest room of her apartment after he broke up with his wife of two marriages post Cate. While he Skypes with wacky strangers about conspiracy theories and subsists on delivered Chardonnay and curated cheeses, Cate tries to move on from Dana, her real love who is unfortunately committed to another woman, by dating the ethically and morally challenged Maureen who still might, Cate thinks, have enough redeeming qualities for theirs to be a serious, enduring relationship.

In short, Cate’s life is a mess, but she’s determined to stop taking money from her parents, deal with Graham—pushed over the edge by Trump’s election—and finally get her career as a set designer on a secure footing. While Dana tries to seduce her into resuming an affair, Cate tries to focus on finally becoming a real adult. We see her potential for it, too: she adores Graham’s rescue dog, Sailor, and takes responsibility for him. (Sailor’s presence in the novel as a character-revealing device is genius.)

Her mother is around, but no help; she expresses her disapproval of Cate regularly and effectively. Cate’s best model of stability is her closest friend since childhood, Neale, who has a son. Perhaps because Neale is not lesbian, the relationship isn’t complicated by romance, and the love and loyalty between the two has lasted. They are, in effect, family to one another, and Cate helps Neale nurture her teenage son:

“They are close in their own way. She was there when he was born. Never having gotten it together to have a kid of her own, she mooches a little of him off of Neale. She’s tried to occupy a place somewhere between parent and friend and aunt. Nondisciplinary like a friend. Older, with good advice at the ready, but not the aunt whose crepey, powdered cheek he’s required to kiss. And after Neale’s marriage was over and Joe’s father was off to India, Cate’s tried to be around even more.”

The reader sees in brief chapters set in a different font, the emerging story of sociopaths Nathan and Irene, like a disturbance in the atmosphere. A savvy reader guesses that a front is moving in. And, of course it will, it does. It snows, and since Cate’s the one with a four-wheel drive vehicle, she’ll pick Neale up for yoga. When she arrives at Neale’s, Cate comes upon the violent storm that will forever change her, change all of them.

In this exquisitely written, psychologically sophisticated novel, rich in insight and sensitivity to human vulnerability, Anshaw suggests that shared tragedies do not necessarily draw human beings closer. “The next morning, in spite of being in an apartment overstuffed with an ex-husband, a boy, a dog, and a girlfriend, Cate wakes shivering and sore everywhere, also massively alone. She understands she has arrived on the other side of everything. No one is over here with her.” To go on, sometimes people have to move on, and apart. Perhaps the good news is that they find a way to make their way.