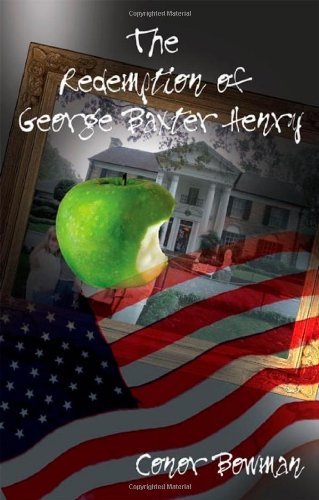

The Redemption of George Baxter Henry

“. . . head-spinning, rope-clutching, canvas gnashing . . . a hilarious contemporary farce, . . . genuinely hilarious. . . . The way Conor Bowman tells his story is a pure knockout.”

Though Conor Bowman’s The Redemption of George Baxter Henry barely stretches beyond novella length—the work tips the scales at 140 pages—this is one of those pound-for-pound narratives that punches well above its weight.

The story and, in particular, the characters resonate with the reader for a head-spinning, rope-clutching, canvas gnashing length of time even after the reader has finally closed the book. This is a tale that performs Grievous Bodily Harm (GBH) on our expectations, which uppercuts through our politically correct defenses, and then slyly digs us below the belt for good measure.

This is a hilarious contemporary farce, one in which Conor Bowman proves himself not just an adept writer—he’d already proved this in 2010’s The Last Estate—but one who signals to us that he’s ready to step up a couple of divisions. Perhaps he’s ready for a crack at the title. Because not many authors can do funny well. Not many writers are genuinely hilarious. And though comedic writing is often frowned upon—and often it seems as though some writers truly believe it is easier to make people cry than laugh—Mr. Bowman here mines the rich seam of comedic Irish fiction and he steps it up a gear. Indeed, his stream of consciousness style is eminently Joycean (though much, much funnier).

The Redemption is a condensed family saga featuring an extremely eccentric cast list. Told from the point of view of the patriarch, George Baxter Henry (GBH), it is the story of how the Henrys travel to France on a make-or-break vacation to sort out their numerous problems.

GBH is an engaging character. Bitter, often acerbic, he sees the world through cynicism-tinted spectacles. What’s more, he’s often petty and vengeful. He’s mean, childish. But he’s carried through by his wit and his humor. His asides have us rolling on the sidelines. Here, in his cunningly unreliable narrator, Bowman has created a unique voice.

And then he’s surrounded it with the eccentrics. There’s his mother-in-law, Muriel, an aging former silent screen star who now has rather a lot of trouble keeping silent, especially about GBH’s various foibles (and affairs).

There’s his son Billy, who is living the hedonistic rock and roll lifestyle in reverse, becoming addicted to cocaine, climbing atop precarious roofs (I was surprised there wasn’t a TV thrown from a window episode) before he’s even signed a contract with a record company (GBH won’t let him, not until he’s provided “four weeks of clean urine.”)

There’s Iska, GBH’s daughter, who, bizarrely, is writing a book about apples. And then there’s George’s wife, Pearl, for whom the trip has become a test, to ascertain whether their marriage really is worth saving (Muriel, her mother, certainly thinks it isn’t.) And though the family is outlandish, superficially revealing themselves as caricatures of real personalities, their problems prove to be universal ones.

The narrative begins with a bang, or rather with a toilet scene: “on a 747. The noise was absolutely mind-blowing. People shouting and screaming, and stewards and stewardesses (sometimes there’s little enough difference) shooting past each other in the aisles trying to formulate some plan to extricate Billy’s head from the toilet bowl.”

After rescuing Billy, the flight crew asks GBH whether his son has taken any non-prescription medication. GBH answers in what the reader will soon recognize as his typical style: “Oh no of course not. He inhaled the lot from humming an Eric Clapton song by accident.”

Soon GBH gets into full flow. His interior monologue gears up for the fight, and it is taking no prisoners. “Children,” he decides, “are the single greatest drain on the world’s finances after global warming and oil-slick clean-up costs. The most blatant lawyer/client rip-off is only in the shadows when compared to the financial fraud visited on parents by their children.”

And then, upon their arrival in France: “We didn’t speak French, but then that’s not a problem for Americans; all we do is shout (or overthrow the local regime) in order to be understood whenever we’re abroad.”

But France provides him with other problems. His mistress is leaving him answer-phone messages demanding that he buy her a car: “You fucking telephone me to where I’m not, when I’m away, to have me call you from five hours ahead just to tell me that?”

They are forced to lock Billy in a bathroom to make him go cold turkey. Muriel’s close proximity is driving him to distraction, proving herself to be just as acerbic as GBH is with her combinations: “He has serial middle-age infidelity. It’s a condition brought on by a combination of the presence of younger women and the absence of prostate cancer.”

George Henry’s initials are GBH. A conceit that Mr. Bowman makes much of in the text. And for much of the narrative, we fear that he will encounter such pain, that it will be his comeuppance. That eventually the facts of his life—“. . . fifty-something with a cocaine addict for a son and a two-week counseling course for a marriage”—will provide him with a knock-out blow. That he’ll become the agent of his own downfall. We fear that his midlife crisis might become the ruin of him. And in some ways, he’d deserve it.

But in fiction, crimes like Henry’s are surmountable. His sheer vitality, his humor, the way he tells his story, lead to his redemption. The way Conor Bowman tells his story is a pure knockout.