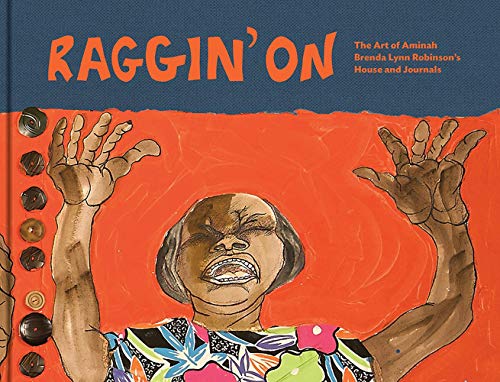

Raggin' On: The Art of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson's House and Journals

Raggin’ On: The Art of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson’s House and Journals may look like a book, but it is really an entire life devoted to art with which an effort to compact, to condense and compile, has been made. The result does not feel like a book, or even like a compilation, but rather like a living, pulsating thing defying classification by using your universal memories—what you remember, the things you miss—to transform itself even as you interact with it, to say this is not finished, this endless story of ours.

It’s a fitting fantasy for Aminah Robinson’s art, a Columbus, Ohio native and MacArthur Award recipient who left her entire estate to the Columbus Museum of Art—a house full to the gutters with works on paper, on fabric, on tile, on dinner plates, on wood, on plastic butter containers and on used and postmarked envelopes, on plants and branches, on glass, on rocks, and on the air—on the very space— between those things, the number of works staggering in quantity, color, texture, and power to reflect the Black experience with a rearranged nod to that community’s tragic transoceanic roots; the point of view, perhaps, more American African than African American.

“By the time I reached nine years old, I was deep, deep into transforming and recording the culture of my people into works of art. The magnitude of research and study of Afro-Amerikans is what I have dedicated my life to. My works are the missing pages of American history,” said Ms. Robinson before her death.

It’s why, for all the excess and variety in her work, Robinson’s stated intention as an artist still fits neatly within the map of contributions we sometimes label “folk,” “intuitive,” or “outsider,” and that seeks to illuminate underrepresented worlds of meaning in partnership with that total freedom to create of the self-trained artist with nobody to answer to and no interest in developing a style or becoming a brand. It is a mindset reflected in the heterogeneous charm and endless inventiveness of the folk drawings, paintings, sculpture, assemblage, wood carvings, performance art, and handmade objects lending the field its decidedly bohemian flair.

That said, for all its diversity of form, the work of Black Folk American artists, including Robinson’s, continues to appear united by the intention scholar John Russell would declare for Black folk art in the 1982 pages of the New York Times’ then “Gallery View” section: “It was the role of Black folk art to make the unbearable bearable. When all else failed, and society had given the thumbs-down signal once and for all, art was the restorative that made it possible to go on living.”

Raggin’ On: The Art of Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson’s House and Journals attempts, then, to be a catalogue for the exhibition of the same name that very much follows Russell’s maxim. It includes more than 200 illustrations, essays by Curators Carole Genshaft and Deidre Hamlar among others, and does what it can to organize itself into sections mirroring Robinson’s areas of focus:

The first is “Home as Sanctuary,” about Robinson’s small ranch home in the Shepard neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio, and how it birthed and shaped her practice of excavating art and heritage from the everyday of her life.

“Beginnings,” features the art Robinson created as a child, a teen, and later as a young adult, striking for the clarity of purpose and insight of the then young, self-taught artist.

“Street Cries” depicts the neighborhood where Robinson grew up, like so many poor places, a community where strength of spirit worked to keep the hopelessness of extreme poverty at bay, while protecting the lively possibility of art.

“Ancestral Voices: From Bondage to Freedom” shows Robinson, the preserver of heritage, waking her dead elders, enlisting them through extensively and painstakingly documented narratives to tell her community’s history in varied visual, and visceral ways.

“Raggin’ On,” which was a lifelong focus for Robinson, features the strong, “no-nonsense” women from which she descended, as well as narratives from her travels to the Middle East, South America, and Europe.

“Journals, Texts, and Music,” captures her extensive collection of journals covered in works of paper and either ink or watercolors, a detailed view into her artistic mission and intention, as well as on her maniacally generative creative process. One such journal includes details of her relationship with her great aunt Cornelia, a diviner who inspired her series, Themba: A Life of Grace and Hope:

“One day, my aunt Cornelia asked me to get a bunch of peach leaves that were on the kitchen table. As I approached her with the peach leaves, she was divining an extremely ill sister, with whom she lived for the purpose of curing her sickness, divining the hidden and controlling the events of the day. Aunt Cornelia was performing sacred rites of religious spirituality on her sister BERTHA,” she writes in red ink, the words jumbled like marbles on the bowl of the page, including the crossed-off mistakes, and the child’s syntax, and the patches of ink erased by time and, maybe, water that ran right next to the exploding color of her drawing of Great Aunt Cornelia divining and healing, but also controlling those she loved.

The final section, “Material Matters” brings together her three-dimensional work, celebrating her use of recycled household and odd natural materials to create organic art extending her domain over medium and proving her steadfast commitment to documenting the secret and the private along with the public, but ignored, parts of her heritage. The sheer number of efforts in this section and others, and the discipline of recording even unremarkable histories over more than 60 years, might, combined, be the feat rightfully transcending Robinson’s life, placing her work alongside renowned Black folk American artists like Sister Gertrude Morgan, Romare Bearden (at his core), Nelly Mae Rowe, and William Edmondson, for others to document.