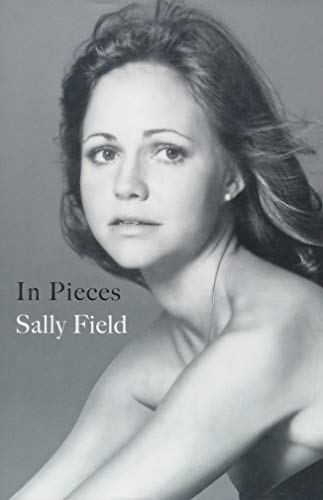

In Pieces

Somewhere in the middle of this revelatory and emotionally powerful memoir by Sally Field, she unpacks a story that is a case study in what Hollywood’s casting couch was like, even for an actress who had already starred in two network series—Gidget and The Flying Nun.

Field’s career was in a lull after those two shows so she was incredulous and delighted to find herself auditioning (it was her first audition ever) for the part of a sexpot in Bob Rafelson’s film Stay Hungry. At that point, director Rafelson was a hot ’70s new wave director, and his resume included the landmark film Five Easy Pieces with Jack Nicolson.

Field got the audition for Stay Hungry because of a female casting director who believed in her, but Rafelson wanted no part of her. Still, he had to admit that she read for the part better than anyone else. As Field writes, “He had a hard time owning the idea that he’d be hiring the Flying Nun . . . and it was driving him crazy.”

Rafelson asked for one more meeting at his house. A housekeeper led Sally to his bedroom and was dismissed. He sat on the bed and “he told me to take my top off so he could see my breasts, saying since there was a nude scene in the film, he needed to figure out how to shoot me.”

Field desperately wanted to jump start her career in films after television so she did what Rafelson asked. He seemed satisfied: “Okay, Sal, the job is yours. But only after I see how you kiss. I can’t hire anyone who doesn’t kiss good enough.’ So I kissed him. It must have been good enough.”

She got the job but the sexual abuse did not end there. On set, Field says Rafelson stopped the entire production early on and had the entire crew vote on whether they thought Field was sexy.

“They unanimously voted that I was grade-A material . . . I tried to laugh, to go along with everything, to be all easy-breezy,” she writes.

You can guess what happened next. Rafelson was clearly grooming Field because he soon showed up at her bedroom door later one night. “I had no problem letting him into my room and my body. Easy-breezy . . . when I look at it through today’s eyes and my now 71 years, I’d like to bash him over the head. But I wasn’t anyone’s victim. I was a 28-year-old grown up, and in ’75 it seemed like acceptable behavior on his part.”

So this type of behavior hardly started with Harvey Weinstein and, like Weinstein, Rafelson has denied the story since this book was published.

It’s juicy stuff but, even if the truth hurts, Field puts it out there. Burt Reynolds, who said Field was the love of his life, abused Field emotionally with his controlling behavior. He was constantly undermining her confidence, telling her not to bother to travel to Cannes for the screening of Norma Rae. He tells her she won’t win a thing and she believes him. As everyone knows, it was one of the highlights of Field’s life and she won the best actress award before going on to win the Oscar.

But the sad truth is that Field’s abuse actually began in her family. Her stepfather, a somewhat infamous stunt man appropriately named Jocko, said he “needed” he very young Field to walk on his back after a day of stunts. He told Sally’s mother that it helped relieve the pain but soon—alone in the bedroom with her—Jocko turned over and asked Field to walk on his genitals. It wasn’t long before he was climaxing as his penis touched her genitals.

It’s heartbreaking to read her thought process, even now when she’s a senior citizen. “He loved me enough not to invade me. He never invaded me. In all the many times. Not really. It would have been one thing if he had held me down and raped me, hurt me. Made me bleed. But he didn’t. Was that love? Was that because he loved me?”

Field eventually has it out with her mother Baa many years later who tells her that Jocko later had told her of the abuse and asked for Field’s mother’s forgiveness. It’s a highly charged scene.

While Field mines her old journals and press clippings to get as close to the truth as she can, she also tells many humorous stories, such as the time she was chosen to be a presenter at the Golden Globes.

What’s great about many of the stories is that they’re from a different era when celebrities didn’t have so many handlers and not every moment was preceded by endless rehearsals. Because she was The Flying Nun, Field agreed to “fly in” to present the award on cable wires but balked at wearing her character’s nun outfit.

Without any rehearsal, the backstage guys hoisted Field up above the auditorium and sent her hurtling toward the stage where she realized she was about to be caught none other than John Wayne. The Duke did his job well and held Field up in the air as she announced the award for best newcomer—Dustin Hoffman for The Graduate.

Field mixed with a lot of big and famous celebrities and had many memorable, sometimes vaguely threatening, moments like the time three members of the Monkees cornered the Flying Nun in her dressing room trailer. All of them were high, she says, and, laughing hilariously, Davy Jones asked if she were good at giving head.

Sally didn’t even know what he meant so, wanting to be hip and agreeable, she said, “Yes sir, you bet!”

That sent them into even more laughter but before anything happened, Field was rescued when an assistant from the Monkees TV show dragged them back to the set.

While the stories and revelations of this memoir are first rate, the writing is sometimes matter of fact. The book does drag here and there when Sally—a long time therapy patient—devolves into psychobabble. Same goes for her “acting process” with legendary acting coach Lee Strasberg. The stories of her and Lee can be long and one doubts the average reader will care very much.

But let’s face it, Field has a generation of baby boomers who adore her, and when it comes to this memoir, chances are they’ll like it, they’ll really really like it.