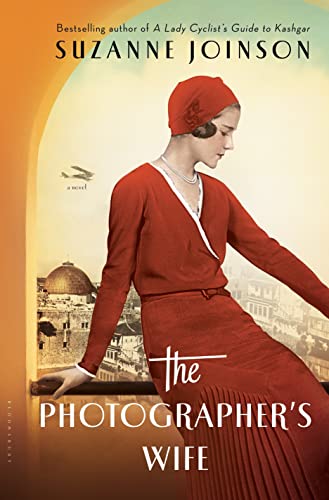

The Photographer's Wife

Prudence Ashton, the narrator, is not the photographer’s wife, rather it is Eleanora, Prue’s sister. Eleanora is a beautiful and dangerous woman who scandalizes 1920s society to marry her Arabic lover, a photographer named Khaled. But Eleanora’s marriage is not the premise of the novel; readers won’t get to learn much about Eleanora, making the title that much more distracting.

Prue is eleven. Her mother has been institutionalized, and she goes to live with her father in Jerusalem, who works at a government job. Prue’s father is an architect burdened with a job meant to modernize Jerusalem with public parks. In reality, he is meant to whitewash this part of the world, making it more like London and less like itself.

The Photographer’s Wife jumps around in time—1920s to 1927 then 1933, 1937, and 1942—with an omniscient narrator and then Prue. There are two stories: The first is Prue’s life in Jerusalem and the relationship between Eleanora and the wounded WWI soldier Willie, and the other is Prue as a grown up with a philandering husband and their son in Shoreham on the eve of WWII. The point of view switches can be confusing.

An older Prue has forgotten much of her childhood and is an artist, having forsaken her Kodak camera in the desert, and works on Palestinian sculptures making avant-garde political commentary. One day Willie appears along with rumors of another war and his country’s loyalty in question, and Prue must remember things she has left behind in Jerusalem to save herself and her family.

Joinson doesn’t set the stage particularly well, and readers are left in a blank space, trying to understand the cultural and historical background of the country and its people. The turns of phrase and descriptive bits of narrative Joinson does use are overblown, like poetry attempting to be deep but just sounding like a young poet attempting meaningfulness. Readers will be doing a lot of eye-rolling, unless they are fans of saccharine prose, particularly when it comes to Prue narrating her thoughts and connections with her son.

The setting will be exotic to many readers, but fans of 1920s and 1930s setting in historical fiction will be disappointed at the lack of detail. History buffs of this time period and country will be annoyed by the small hiccups no one caught or edited.

Readers will also have a difficult time identifying with the characters; there is a lot Joinson doesn’t reveal (as if she is also keeping secrets) that makes it hard for readers to build a connection. Even though readers learn about Eleanor, the premise of the novel is more about the atrocities during the war, the way memory works, and how each cultural entity in Jerusalem is a stakeholder to memory and atrocity.

This novel reads more like an attempt at highbrow literary fiction in need of tighter prose and more careful editing for content and conceit.