Petty Business (Judaic Traditions in Literature, Music, and Art)

In the opening pages of S. Y. Agnon’s 1945 magnum opus Only Yesterday we learn that in the first decade of the 20th century its protagonist Isaac Kumer, a Galician shopkeeper’s ne’er-do-well young adult son whose age peers already own their own stores, is a Zionist who wants to move to Palestine, work with his hands, and build the Jewish homeland.

Most Central European Jewish store owners Isaac’s age were murdered in the Holocaust three and a half decades later, but a perspicacious few sold their stores and moved to Palestine in the 1930s, not out of idealism but self-preservation, and resuming their previous vocation would become Tel Aviv’s middle class store owners.

Readers of Israeli fiction in translation have become acquainted with members of Israel’s rural pioneering founding generation and their urban and suburban university educated upper-middle class grandchildren, poor North African immigrants in Ronit Matalon’s The Sound of Our Steps (also reviewed in NYJB), but until now such readers probably have not met Israel’s less educated multi-generational Ashkenazi shopkeepers, many of whom in recent decades have been forced by globalization and corporate retail behemoths to find alternative livelihoods.

Petty Business, the second of Yirmi Pinkus’ five novels and the first to be published in English, satirically portrays the life of a family of Tel Aviv store owners with both fondness and humor over one year—1989, a time in which neighborhood mom and pop stores were being put out of business by larger chain and department stores, just as the latter are now under pressure from Internet vendors.

But hindsight is always clearer: “From time to time the events of our lives are revealed most clearly only in retrospect, after the evasive liquid of action has been poured into the clear glass bottles of language.”

The matriarch of one of the novel’s retail families, the late Hinde Shlosman, opened a perfume shop on Judah the Maccabee Street in Old North Tel Aviv a generation earlier that now in 1989 is owned by her and her husband Tevye’s daughter Dvora Saltzman, who like her mother is also a beautician and whose husband Shraga is an insurance agent.

Hinde and Tevye’s other adult children include Avram Shlosman, a barely closeted gay antiques dealer; intellectually disabled celiac patient Bina Shlosman, who lives with and is cared for by Dvora; and Tzippi Zinman, a fashion industry freelance entrepreneur and stylist married to to grocer Yosef, whose Judah the Maccabee Street delicatessen he inherited from his parents Rachel and Berl Zinman.

The third generation includes (Yellow) Tuvia Saltzman, a graduate student in the United States; (Fat) Tuvia Zinman, like his mother a freelance entrepreneur; and Shirley Zinman, a high school student who plays avant-garde music on a bowed saw. A useful flow chart at the beginning of the novel illustrates the characters’ family relationships.

These family members may be the most diaspora-like secular sabra characters readers are likely to encounter in Israeli fiction. Their Hebrew is seasoned with loan words from Polish, Yiddish, German, and when they are being pretentious, French. They appear to be apolitical, are not preoccupied with the conflict with the Palestinians except as a matter of public safety during the first intifada, rarely mention their army service, which for most Israelis is a transformative rite of passage, and their attitude towards their government is expressed as fear of and antipathy towards tax authorities (who suspect independent businesses of hiding income).

Though mainly preoccupied with getting and spending money, this family is also fascinated by one another’s intestinal tracts and the solid and gaseous products thereof:

“The Zinmans, and their relatives the Saltzmans, preferred to focus on their intestines and the functions therein. They took an interest in knowing what was excreted from people’s bodies and under what set of circumstances, and whether suffering was involved or perhaps pleasure. They always listened cheerfully to one another, encouraging the speaker to report on everything taking place within his bowels. … Upon leaving the lavatory they would issue comparatives and superlatives, and if some special episode had occurred they did not hesitate to pick up the phone to the others. No texture was foreign to them:

“a volcanic stomach was thought to be a sign of virility in a man and an expression of joie de vivre in a woman. Flatulence was so pleasant to them that they created and bestowed on it its own special language, each term representative of a different embodiment of the phenomenon, from minor releases, the traces of which evaporate in a flash, to Napoleonic displays that make a formidable impression on others. And if their luck did hold out and someone among them passed wind in a manner heard by all, their laughter could bring them to tears.“

The family relationship with the greatest psychological tension is between sisters Dvora, who is responsible, risk averse, their late mother’s favorite and heir to her store and apartment, and Tzippi, a more adventurous and creative free spirit who contributes less than her share to the care of Bina and then in the form of fun outings while Dvora has to be the one to tell Bina “no.”

“Some would say she was justified in her anger at her sister, who tended to scatter big promises without a thought to consequence. But this was neither negligence nor hypocrisy; in spite of the tendency—attributed to her in the family—to shirk responsibility, Tzippi Zinman respected the principles of morality no less than the others. The promises she made stemmed from a deep, noble place: the fact that no actual deed could awaken in her soul the same kind of excitement generated by the mere announcement of her intentions.”

Meanwhile, the perfume shop is rapidly losing customers to department stores, while the delicatessen, which until recently paid for twice yearly vacations to Austria’s Tyrollean Alps but whose unsold challah loaves on Friday evenings now constitute the difference between profit and loss, is losing customers to supermarkets. Tzippi and Yosef would like to take one last vacation to their beloved Seefeld, Austria, and this time they want the extended family to join them.

How will Dvora pay her and Shraga’s fare? Tzippi encourages her to buy locally made garments direct from the manufacturer (this is just before inexpensive imports killed Israel’s textile industry) and sell them that summer at the outdoor vendors’ mart Tzippi manages on the grounds of Kibbutz Shefayim’s water park situated near Tel Aviv’s northern suburbs.

Tzippi offers her son Fat Tuvia as Dvora’s business partner and guide through every step and negotiation. Will Dvora suspend her better judgement, and if so will the plan work, and who will mind Bina?

The novel’s title in the original Hebrew edition is the Aramaic phrase Bi’zer Anpin, which means “on a small scale, in miniature,” and this family and their enterprises are a microcosm of a lower-middle class retail subculture at the end of an era.

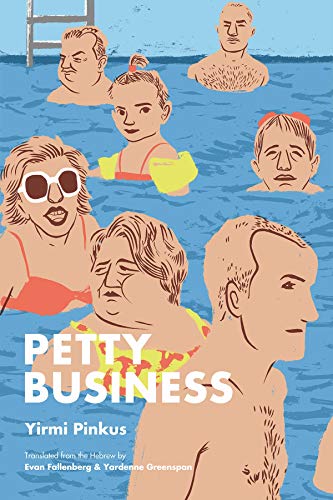

Overseas Pinkus is better known as cartoonist, and his book cover illustration of bathers in the waterpark swimming pool provides a preview of his satirical take on that subculture whose narrative portrait is also poignant. Pinkus’ mastery of language is every bit equal to that of his visual medium, and translators Evan Fallenberg and Yardena Greenspan do a fine job of conveying his varied prose into English.