Peanuts Every Sunday, 1956–1960 (Vol. 2)

“This is over 200 Sunday pages of glorious art and words by Charles Schulz, covering an early, key period in what made Peanuts the best ever.”

The pages that center on Charlie Brown’s battles with his kite seem to capture Peanuts at its best. They are filled with optimism, hope, and shattered dreams. Each attempt to fly the kite is the same, starting with the knowledge that this time it will work, putting the kite together, watching it fall, picking it all up, and doing it again next Sunday.

Just watching Charlie Brown take the time to tie on the tail. Seeing him work on the small pieces of wood that become the frame for a kite. To hear him optimistically state each time that the kite will fly . . .

He never quits, and that is why so many love Charlie Brown and the gang from Peanuts. The tree may eat the kite or it may fly down into a sewer of its own accord, but each and every time Charlie Brown rises to try again.

While the Peanuts daily strip was four panels of near Zen beauty, each scene playing out in minimalist simplicity, it was the Sunday page where Charles Schulz found the space and room to make his band of Li’l Folks swing like the tightest of jazz ensembles.

After seeing what modern newspapers have done to the Sunday comics page, viewing the pages inside Peanuts Every Sunday, 1956–1960 (Vol. 2) by Charles Schulz is like being handed ice cream on a 90-degree day: you had no idea what you were missing until it was put right in front of you.

Presented in their original dimensions, colored exactly as they were originally over 50 years ago, this new collection gives Schulz’s art the showcase it deserves.

As the Sunday comics page has shrunk to the point where it is almost indistinguishable from the advertisements for grocery, muffler, and mattress stores that it shares the page with, this book reminds us of the glory once found in a Sunday comics page.

This is Cinerama in print. Seeing these Sunday pages is the equivalent of seeing Lawrence of Arabia in Super Panavision 70. It is the beauty of modern art, whether film or comic strips, being seen as it was originally meant to be.

And that is just one reason why this compilation is so important. Because we haven’t really seen that world of willful kites, errant baseballs, and fussbudgets in this form for so very long. We have seen the advertisements for insurance. We have seen the holiday specials, and we have seen the figurines, greeting cards, and snow globes. With this volume we see it all in the minutes before all that white noise came to the fore.

This is Schulz creating pages and building rhythms right before that commercial familiarity begins to take hold. The characters are still forming. Even though it has been six years since the daily strip has started, at this point Peanuts has yet to assume what would become its final shape, the familiar gags and storylines that would come to be in the early sixties.

Much of this growth in Schulz’s work is covered in Chuck Klosterman’s terrific introductory essay. He also addresses the larger meaning, the reason the strip has become what many to be the best ever.

With insight and precision he creates a commentary on the relationship to Charlie Brown and the world around him. He offers the idea of what Charlie Brown and Lucy mean in a much bigger scheme of things. Seeing one as eternal optimism and the other as a reflection of the real world.

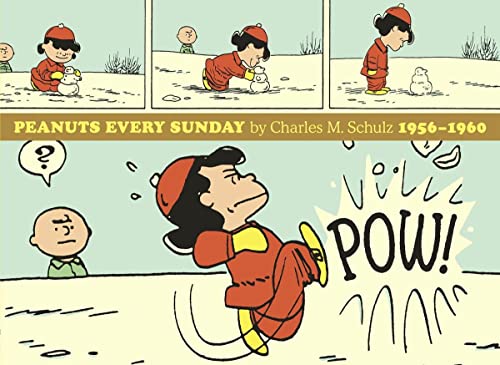

Yes, Lucy is tough. The cover image to this volume shows her kicking the heck out of a snowman. On another page, When Linus pesters her to read a book to him she eventually says, “A man was born . . . he lived and he died. The end!” Yes, she is sarcastic and bossy.

But in a series of strips centered on Charlie Brown and his kite she is right there for him. Just like the world is. There supporting us one minute, the other pulling the football away from us.

Above all she is like so many of us: human. Prone to all the problems and mixed emotions that being human entails. Capable of sincerity one minute and the next commenting on Charlie Brown’s trusting nature. She seldom, if ever, edits herself in a way we all wish we could.

One quality that Schulz brings to his art is his ability to convey wickedly funny slapstick inside the comic page. His pratfalls and kicks never hold the meanness seen when Abbot slaps Costello or Moe takes a swipe at the other two stooges.

It is the mild violence of real life. We all fall. Something can always trip us up. The artist creates big, extraordinarily wild sound balloons or shattering speed lines which accompany fastballs that can strip a pitcher of their clothes. It doesn’t always have to be physical, either. It can just be a cutting remark.

And yet we always know that everything is okay.

By the time this run of Sundays begins several characters had fallen by the wayside, but a new one comes along to steal everyone’s hearts. Schulz introduces Charlie Brown’s sister Sally near the end of this collection.

From the very beginning she personifies adorable in a way the others really can’t at this point in the strip’s growth. Sally adds an important counterpoint to the general toughness found in Lucy.

While Charlie Brown is still at the center of the strip, Linus begins to take up his share of pages. Schroeder gets in some delicious piano licks, and snowmen are doomed to fall due to either sunlight or Lucy’s swift boot.

This is over 200 Sunday pages of glorious art and words by Charles Schulz, covering an early, key period in what made Peanuts the best ever.