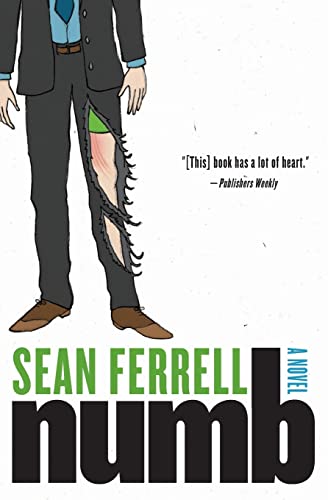

Numb: A Novel

Sean Ferrell’s daring first novel, Numb, is a Barthian fable which endeavors to chart a course through the murky waters of sensory overload in the modern world. It’s the search for a voice—the quiet voice of identity and selfhood—within the relentless multimedia clamoring of images and signs. It’s about the yearning for something authentic in a culture which people and their stories have become consumables.

Numb is a story about love and friendship and desire, narrated by a protagonist, Numb, who cannot feel pain and has no memory. His often claustrophobic, unreliable first-person narration is the key to the success or failure of the novel, and it is sometimes difficult to feel sympathy for him—the narrative threatens to lag in some places—but Ferrell’s controlled anger allied with his fertile imagination carries it through.

Numb’s journey to understanding the unfamiliar world in which he has been thrust starts at the circus. He has only the briefest of memories of life before the circus, but soon finds his niche as the biggest freak in Mr. Tilly’s freak show: the man who can feel no pain. Yet the circus still struggles to make ends meet, and when a money-man approaches Tilly with a proposition—he wants to pay to see (and record) Numb confronting Caesar the lion in his cage—Tilly has no choice but to accept.

But the encounter with the lion does not go as planned; Caesar, old and exhausted from the heat of the tent is a sad approximation of the ferocious lion. He’s sick, unsteady on his feet, only managing a cursory swing at Numb, the trespasser in his cage. Nevertheless, the swing causes a deep wound and as lion and man lie in the cage sweating out the wait for a doctor and vet, Numb determines to leave the circus for good, bringing with him his best friend, Mal. Numb is acting vaguely on the one clue he has as to his former life and identity: a battered and blood-stained business card he finds in the pocket of his suit. The business card is for a dress shop in New York, and this is where they head.

At this stage, Numb reads like the opposite of a “run away to the circus” narrative, but soon Numb finds the “real world” New York just as confusing as the circus: Times Square is like “a carnival,” the streets alive with blaring horns, shouted messages, and flashing neon signs. Numb is overwhelmed. The semiotics of this world leave him in a spin, he can’t get a grasp on what anything really means. Ferrell name-checks Roland Barthes’s Mythologies, a work that explores how bourgeois society and its media assert values through signs. And signs play an important part of this novel, both shaping and blurring Numb’s world.

There are a number of recurring images/signs within Numb, starting with Mal’s television “with a coat hanger duct-taped to the antennae,” and two channels “cloudy with static.” The TV follows them from the circus to New York acting as a pathetic fallacy of Numb’s quest to discover who he is. He tries to find his own way of understanding the messages which are broadcast, in the end, covering the screen with pages from a Braille copy of Mythologies: “When I finished, Braille pages covered the television screen. Small loops of masking tape held each page in place. I turned on the television and found a channel with a signal and played with the antennae until the sound cleared. The images illuminated the pages from behind with a wavy, multicolored light. The colors hinted at what the images were but I could not be certain what I saw.”

Then there are the messages that Numb sees on the T-shirts of his friend Mal, and also Redbach, the bartender from a low rent local bar where Numb starts out in New York, making money from allowing people to nail him to the bar. These T-shirts variously read, “ASK ME HOW I FEEL,” “HERE WE GO AGAIN,” “IMPEACH PEDRO,” and later, simply, “ASSHOLES.” The messages become increasingly mixed, increasingly confusing, just like the television. And even when other characters speak to him, when their messages should be easy to understand, they constantly seem to speak with their mouths full of pretzels or crackers.

Numb starts to feel communication fatigue. He goes to the store to buy DVDs and CDs: “With such a wide assortment to choose from I lost track of where I was in the store (. . .) Occasionally I’d see a name that would pop out at me and I’d recognize it, having heard it from the Brailled-over television in Hiko’s living room, or seen it along the side of a city bus, on a billboard, squeezed into place around the headlines of People, Us, and other less reputable publications. Album covers like artifacts, hieroglyphs depicting the hunt for power and prestige and pagan rights; a young girl dressed like an oversexed woman, a group of young men on a cover sticky with bright pink CLASSIC stickers . . .”

Meaning becomes lost for him; he can’t decipher the many hieroglyphs. The world is distorted: “everything just had the hint of warp to it.” And yet, the star of his fame starts to rise. News of his being nailed to the bar spreads across town. He walks away from being run over by a New York city bus and the grainy CCTV footage makes the news and hooks him an agent. On their way up to New York after escaping from the circus, Mal used to say to him: “‘Someday we’ll be on TV.’” And as soon as they arrive in New York: “Mal avoided all talk of my reasons for going (…) and instead focused on becoming famous. He never bothered to explain what ‘being famous’ meant, only that once I started putting nails into myself it wouldn’t take long.”

His agent, Michael, snags him an appearance on a talk show in which he appears with a character named Johnny (who bears an uncanny, and acknowledged, resemblance to Johnny Knoxville from Jackass). Numb also participates in cross-promotional work with some of the other artists in Michael’s stable, particularly with Hiko, a blind sculptor, and Emilia, a sadistic model stroke actress stroke celebrity. After a while, Numb decides: “This is what my life will be, I realized. Michael would take me to meet executives from Budweiser, Coca-Cola, or TD Bank and convince them I could say lines like ‘Make banking painless”’” He’s become a sign himself, or been translated, shorthand, into one by the media and cult of celebrity. And he’s further away than ever from discovering who he might be.

“Nothing seemed real at the Hotel Thomas. I never watched the television but left it on. I rarely felt like reading but I requested magazines and newspapers that at first piled up, then were replaced with new issues, then were placed in order of arrival, all without ever being read. Once-used bars of soap were switched out for new ones. Clean glasses in tissue paper appeared, lip prints and finger smudges on the old ones gone for good. I lived in a constant state of consumption. I ruined new things.”

Mal, who lurches between jealousy at his friend’s meteoric rise to fame and concern at his apparent inability to understand anything, advises:

“‘The real stuff happens while you’re waiting for the subway, choosing what you’re gonna do for the rest of your life. Sometimes these moments are shared with one or two others, but mostly it’s just you and you. So you go home and you debate this over with yourself, and when you don’t come to a conclusion, then you know.’

‘Know what?’

‘That you’re fucked. You’re not even sure of who you are, let alone what you want.’”

But a number of emotional sucker-punches send Numb even further away from the truth. Mal dies a horrible death, Emilia leaves him, taking with her her pound of flesh, Hiko finds out about his affair. More and more films of his escapades appear on the Internet, most of them without his knowledge, some of them, he fears, not even featuring him: “I wanted none of my films to enter my home. I felt them rising outside, like a tide . . .”

The already fragile world starts to disintegrate around him; he doesn’t know what signs he should read anymore. He travels to Los Angeles and even finds himself trying to “read” the scratches on the wall, where Mal reputedly had a car smash, to try to make sense of things. “I watched the sides of the road, the barricades and guard rails. I hunted for scratches, dents, any sign of collision. I counted them on my fingers, like a collector.”

He’s in L.A. because Michael has set up a deal for a studio to make the story of his life, a story which will be a complete fabrication because Numb (and despite their detective work, everybody else) has no idea of how Numb came to be who he us. At the pre-production meeting, he encounters some of the actors who will be playing key roles in his life but he does not even recognize them as people, let alone versions of characters he knew: “Ray said something about being glad to finally meet me. I watched as he moved between me and the X light, became nothing more than a shimmering silhouette, a cutout of a perfect man, complete and happy in his own presence, removed from the room by light and dark.”

Once again, Numb flees, returning to New York searching for traces of himself. “Underneath the blood, or maybe deeper in the wood, there had to be some imprint I’d left behind, and not just here but out the door and down in the street. Deeper in the ground or in the air surrounding those places I’d lived . . . there had to be something of me there, something that would remain.”

The reconciliation with Hiko and his apparent starting to feel seem rather too glib for what has already happened in the narrative (“. . . I began to sense a jingling along the hairs of my back, the electricity in the air, warping and weaving around me. The tingle ran up my spine and danced across the back of my skull,” and: “Again, beneath the tug burned that other feeling, something I wanted to retreat from if it grew much larger, which it did. My arm twitched.”). And some may take issue with Numb’s meteoric rise to fame—from dingy bar to being thronged by fans on the street in a mere few pages—but this is the nature of the new world we live in today. The world in which Susan Boyle becomes a star, and fame can be as rapid as it is fleeting. Andy Warhol’s fifteen minutes of fame is starting to look like an overestimate.

Numb can be patchy in places, but there are startling flashes of insight and poetry on Ferrell’s part: “The needle stopped, then tugged again slowly. It felt like Morse code in my skin,” and “every morning the bathroom looked like a tiled paradise: white, chrome, reflective, cold, dry. I left it damp, foggy, littered with wet towels. Like paradise after the dinosaurs came,” and “his hair and beard, one knottier than the other and sprinkled with bits of paper and cracker, all seemed to be growing leftward with such insistence I thought not of someone having slept for too long on one side but of a plant left near a window to grow toward sunlight.”

This is a highly enjoyable and intelligent read. Sure, there are red herrings (the business card that first lured Numb to New York being a prime example) but the various characters presented cannot be explained as simply pawns in Ferrell’s written world. The quest to discover identity will contain a great deal of knotted, twisted paths, dead ends, false starts, misread signs. The world is constructed as a confusing place and the signposts are written in a language many of us don’t understand.