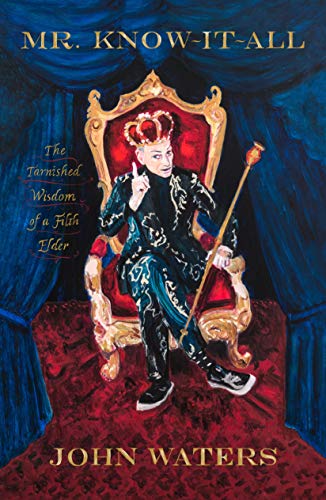

Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder

“Mr. Know-It-All is an argument for deviance, performance, and shock.”

John Waters was the “king of filth” in late-20th century film, with his directorial career culminating in the 2004 film A Dirty Shame. Waters was never again, after that, able to secure funding for a movie. Yet he writes without bitterness: “Maybe my movie career ended where it began—in the gutter. A Dirty Shame . . . was my sexploitation satire and I’m amazed it got made at all.” Like all of Waters’ films, it bombed at the box office. Yet what does it matter? “Maybe it’s my last film. Does that depress me? Not really. I’m hardly misunderstood.”

Mr. Know-It-All is John Waters’ third book. In many ways, it epitomizes Waters’ pop culture work since the death of his directorial career. For a has-been, he’s intensely present: introducing his cult films at colleges, conducting speaking tours, performing cameos in film and television (including the odd children’s movie), taking photos that sell in New York galleries, and enjoying the residuals and royalties of a career defined by mad creativity and joyful obscenity. He’s not bored; he’s just not doing what he’s known for.

The first half of the book recounts his two-decade Hollywood career, wherein Waters came face-to-face with official censor boards and their new power to prevent his films from being distributed. The Maryland Censor Board’s ban on Multiple Maniacs becomes comic genius when reduced to its histrionic excesses: “‘Even the garbage can was too good for it,’ Mary Avara, the head of the censors and my arch-enemy from the beginning of my career, ranted after a judge declared it was ‘obnoxious but not legally obscene.’ ‘The Court’s eyes were assaulted,’ he continued, ‘. . . horrendous, sickening, revoling.’ I guess he didn’t like it.”

Waters’ charming account of his “mainstream” film career encompasses most of the book’s hundred. In keeping with the book’s promise of “tarnished wisdom,” he shares what he learned from his successes and mistakes: “ask yourself, am I the only person in the world who thinks what I’m doing is important? If yes, well, you’re in trouble. You need two people who think your work is good—yourself and somebody else (not your mother). Once you have a following, however limited, your career can be born.”

The other two-thirds of the book is comprised of essays on topics ranging from food to architecture. These vary in quality, largely according to how genuinely engaged Waters is with his subject. “I Got Rhythm,” his essay on music, is largely a reminder that Waters’ taste in music was formed in the 1950s and 60s. His commentary on “car-accident teen novelty records” is on the nose, but 50 years past its prime. Likewise, few today need to be informed that “if you’re a junkie, jazz is for you. Bebop is the sound of heroin, isn’t it?”

In contrast, “Gristle” engages with food and foodies with sharp humor and Waters’ signature appalling panache. In these pages, he demonstrates that it’s possible to violate every stricture of political correctness without regressing into conservative hate-speech. Why go there, when there are so many other boundaries to cross? The titular restaurant encapsulates Waters’ oeuvre in menu form: “We serve foie gras, too, but ours is made from horse corn that was forced down the throats of masochistic ducks who enjoyed being humiliated by the butchest liver-loving famers this side of the French border.”

At his best, Waters demonstrates what obscenity is for. He argues that “the most radical thing you can say these days is ‘I still love sex!’ But you should. A robust sex life does not have to be stopped because of political correctness. You can still be horny, act on it, and not be a pig.” Queer history, as he recounts it, is a glorious, consensual orgy. (Waters, it should be noted, is one of the few gay men to survive the AIDS holocaust of the 80s.) The gay rights scene that emerged was sanitized and bourgeois. It might have achieved legal triumphs, but it did so at the expense of the genuine outsiders who don’t fit the mainstream.

At its best, Mr. Know-It-All is an argument for deviance, performance, and shock. Perhaps if the book were entirely successful, its argument would be undermined. Waters has tried almost everything in his career; only a few fragments have worked, but they’ve elicited genuine cultural change. The pulsating mass of the rest humps across the page, giggling to itself. It is not embarrassed. It knows what it is.