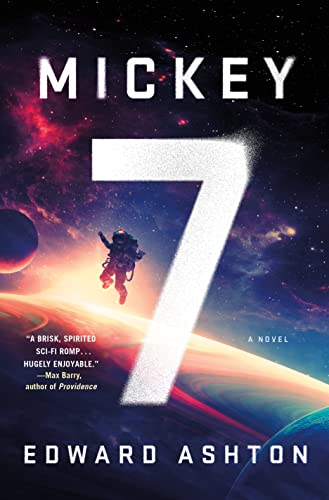

Mickey7: A Novel (Mickey7, 1)

“Ashton’s emphasis is clearly on the moral and philosophical implications of the Mickeys, however, not on first contact, cross-cultural relations, or the evils of colonialism. Edward Ashton does this superbly, wrapping dark horror and philosophical depth in a classic SF adventure story and a carefree narrative style.”

Mickey7 is a smart philosophical satire masquerading as an adventure novel. It draws readers in with flippant black humor and a clever premise, then stabs them in the back with devastating insight into the human talent for suppressing intolerable truths.

The basic premise is simple: Mickey has agreed to die. Whenever his nascent planetary colony has a dangerous mission or a deadly medical experiment that needs doing, he is the one to do it. If he dies, then a new body is vat-grown for him, and his mind is restored from the last backup. From one perspective, he is immortal. From another, he is very much not.

As Mickey describes it, “Imagine you found out that when you go to sleep at night, you don’t just go to sleep. You die. You die, and someone else wakes up in your place the next morning. He's got all your memories. He’s got all your hopes and dreams and fears and wishes. He thinks he’s you, and all your friends and loved ones do too.”

It is blindingly evident from the very start that each Mickey is not the same person as the Mickey that came before, all the more so when Mickey8 is inadvertently created when Mickey7 is still alive. All the characters in the novel, however, including Mickey7 himself for a while, cling to the fantasy. They want to believe they are not, in fact, murdering a crewmate in gruesome ways for their own convenience and safety. The survival of their colony requires some dangerous risks, and Mickey signed a contract. It is his job to die. It is easy to convince themselves when they see him again the next day as healthy and sarcastic as ever.

The characters in Mickey7 respond to this cognitive dissonance in different ways. Some keep repeating the party line that Mickey is immortal. His deaths might hurt, but they never last. Some avoid talking to him or thinking about him at all, not wanting to face what they cannot adequately justify. Some, like Marshall, the colony’s commander, turn their own sense of guilt back on the Mickeys themselves, calling them abominations, as if the moral failings are theirs. Marshall rages and threatens, increasing the pain and horror of the Mickeys’ deaths unnecessarily, as if to convince himself that the Mickeys are no longer human, and he is justified in treating them as expendable tools.

The book is marred only by an abrupt ending that concludes the story’s problems too easily and without answering enough questions. The main external conflict for the colony is an alien species involved in several of the Mickeys’ deaths. The aliens, however, turn out to be much like many other aliens from the science fiction canon, neither very mysterious nor particularly interesting. The conflict with them is resolved with astonishing ease and little acknowledgement of the difficulty of establishing a human colony on a planet already inhabited by a non-human, intelligent species.

Ashton’s emphasis is clearly on the moral and philosophical implications of the Mickeys, however, not on first contact, cross-cultural relations, or the evils of colonialism. Edward Ashton does this superbly, wrapping dark horror and philosophical depth in a classic SF adventure story and a carefree narrative style.