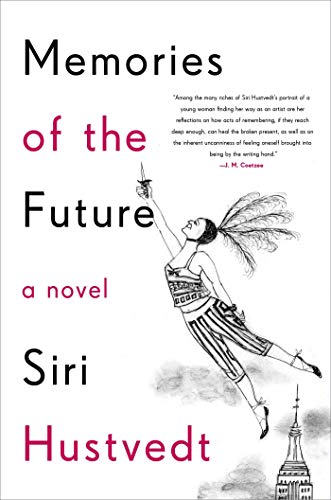

Memories of the Future

“Readers can get really caught up in S. H.’s discovery of her young self. The writing here is sophisticated and literate and the author’s line drawings sprinkled throughout the book add to the story’s whimsy.”

Memories are a funny thing. We all harbor stories of our youth, folklore about how we became who we are, but even though we might not admit it, those memories are colored by time, experience and favorite stories that have been polished incessantly to show us in their best light.

Even our own recollections can’t be trusted and that’s what this charming though sometimes frustrating novel by Siri Hustvedt is about. The lead character is the present day version of the author.

S. H.—as the narrator calls herself—finds an old journal she kept when she moved to New York City in 1978, back when her nickname was “Minnesota.” Since then, S. H. has become the writer she had hoped decades earlier. But perhaps nothing she’s written has affected her like this old journal.

Suddenly, the memories of that past immature life—long relegated to the black and white, grainy footage of memory—pop into technicolor. Characters and incidents long forgotten snap into focus.

It might be hard for anyone under 30 years old to understand what life was like before cell phones but there was a time when even close friends did not photograph and document each other obsessively. Hustvedt, a fine writer, addresses that time in the book:

“I was young well before the craze for self-documentation took over every country on earth, and only a few photographs of me exist from that period. Except for the mirror, the photograph is the only way to view oneself from the outside, and the mirror can no longer show me what i looked like then, but I recall that, in those early years in the city, I would, every once in a while, come as a surprise to myself. When I left friends at a restaurant for the toilet and had washed my hands and was greeted by my reflection in the mirror, I remember thinking, ‘I had no idea you were as pretty as all that.’ There is often a mismatch between inside and outside. We lose our faces completely in the swing of living. . . .”

Chief among the surprises Minnesota discovers in her journal is her next door neighbor Lucy Brite. She finds she has recorded Lucy with all her manic tics in place, and Lucy is a New York character of the first order.

Minnesota hears Lucy each night through the thin walls of their adjacent apartments. It sounds to Minnesota that Lucy is saying “I’m so sad” over and over again. Later, there are several other voices and Minnesota, despite using her father’s stethoscope, can’t quite fathom what’s going on in there.

Whitney, Minnesota’s best friend at the time, tells her that the voices are probably actors preparing lines for a play. Not quite. What is really going on is much closer to Rosemary’s Baby and in due time, Minnesota gets to meet the people behind those voices. Their introduction comes when they interrupt someone nearly raping Minnesota. Afterward, Lucy and the voices bring Minnesota into their private world.

Readers can get really caught up in S. H.’s discovery of her young self. The writing here is sophisticated and literate and the author’s line drawings sprinkled throughout the book add to the story’s whimsy.

But there are problems. The book is comprised of three revolving stories: the mature novelist recounting her discovery, the young would-be writer who addresses her journal as “Dear Page,” and, most problematic, the fiction the young writer created back in 1978.

The push pull between the mature narrator and her younger self is fascinating and works on every level, so it’s disappointing when the fiction of the younger writer interferes. It’s tempting to skip over those pages. Certainly, Hustvedt felt this younger fiction was important but it’s lost on this reviewer.