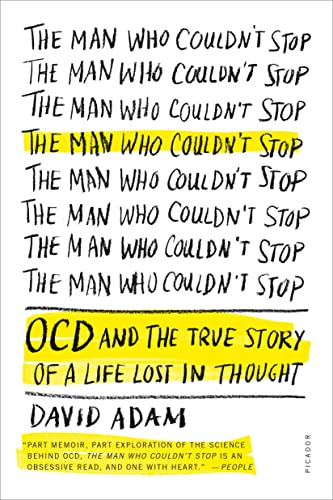

The Man Who Couldn't Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought

The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought is a gripping memoir that blends personal experience with history and complex empirical research. The writing style is crisp, concise, and compelling. These are the elements that make this book superior to others of its ilk.

At the core of this riveting memoir is the ferocious personal battle against OCD that author David Adam has endured. As he explains his own thought process he confesses, ”I obsess about ways I could catch AIDS and compulsively check to make sure I haven’t caught the disease. I see HIV everywhere. It lurks on toothbrushes, towels, and telephones.” The thoughts focus on a kaleidoscope of inanimate objects; however, the most painful parts of the illness are both the inability to logically terminate the thoughts coupled with the inevitability of the secondary phase of acting out the compulsions to, for example, call AIDS hotlines to seek reassurance for even momentary relief.

According to Adam, “Mental health professionals refer to OCD as a secret disease and a silent epidemic.” People who suffer in this silent torture often do so because they believe that their obsessions and the concomitant behavior (compulsions) are repugnant.

Most people do not possess even rudimentary knowledge of this disorder. The stereotype of a person with OCD is someone who washes his or her hands multiple times a day. This behavior is a minute example of symptoms that can occur. The media, for example, assign OCD sufferers with the moniker “dangerous,” and such people are to be feared. This couldn’t be further from the truth. For mental health professionals as well as the many who suffer from OCD, it remains a Sisyphean task to overcome the prejudices that still remain.

One of the most interesting portions of the book is Adam's historical perspective on the illness. Few people have heard about the vast numbers who have the disorder, which according to Adam’s research is somewhere between two to three percent of the population,; this translates into “more than a million in Britain and 5 million in the U.S.” Many famous people are known to have suffered with OCD. He cites various famous historical figures who endured symptoms of OCD. For example, Winston Churchill had overwhelming thoughts of leaping from ships or trains when he traveled and confessed to his doctor about his thoughts of “how he hated to sleep in a bedroom with access to a balcony from which he had the urge to jump.”

The basic symptoms of OCD begin with intrusive irrational thoughts. “The theory used by psychologists who study OCD is that our brains have something called a cognitive idea generator which helps us to solve problems and navigate through life.”

In the OCD patient, these irrational thoughts create cognitive dissonance (a discomfort caused by two competing beliefs within the individual) that can wreak mental havoc. These obsessive thoughts lead to uncontrollable urges along with repetitive behavior known as compulsions.

According to Adam, “An average person can have over 4,000 thoughts per day and some arise out of the blue. Most of these random thoughts can be released by people, but for the person with OCD, they become a source of torture.” They are particularly repulsed by the inevitability of the action or compulsive phase than can be extreme in nature.

Historically OCD was viewed as monolithic in scope but classified as an anxiety disorder. And this myth has long been dispelled as inaccurate. After careful consideration of a cluster of symptoms related to the features of OCD, the official handbook used by clinicians to assess psychological disorders (the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual or DSM) was revised.

Currently OCD is considered part of a spectrum of disorders that share similar features. The spectrum includes myriad diagnoses including body dysmorphic disorder referred to as BDD (a perceived and exaggerated defect in one’s personal appearance) that creates obsessive thoughts about the defect, inevitably leading to compulsions such as covering up with makeup or extra clothing to hide the affected area.

Additional disorders that encompass features of OCD include Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder), compulsive gambling, autistic disorders such as Asperger’s Syndrome, compulsive hoarding, and more.

Adams delineates in detail the evolution of treatments used by experts, including talk therapy that did not work to drastic measures—like frontal lobotomies that ultimately had disastrous consequences—to the current combinations of treatments that include medications and cognitive behavioral therapy.

It is abundantly clear that Adams has a firm grasp on the brain-body ecosystem and the processes that co-occur to create OCD. His precise presentation of the aggregated data in the field of research is unsurpassed in a book that is not considered a textbook for perspective clinicians. In fact, The Man Who Couldn’t Stop: OCD and the True Story of a Life Lost in Thought would be highly recommended for mental health practitioners as well as individuals who suffer from both OCD and related disorders.

If there is any reticence in recommending this book for the general reader, it is the fact that a certain base line of knowledge is essential to totally grasp the scientific details of the complex intricacies of the brain-body system and how they interact; however, what may be considered by some readers a drawback could also be viewed as a giant leap forward in the mental health arena. To be more specific, the author boldly challenges the status quo in the psychiatric community in several key areas. His proposal to restructure the current diagnostic model could fluster practitioners but could also result in more enduring therapeutic outcomes.