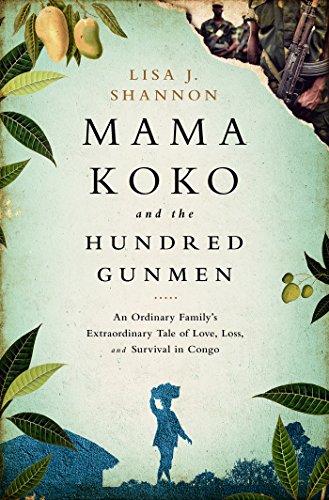

Mama Koko and the Hundred Gunmen

“Beautiful writing . . .”

Lisa Shannon is a young woman with courage, conviction, and a craving for adventure. She is also a good writer. Her tale of what happened in the Congo under the tyrannical rule of Joseph Kony and his Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) will not soon be forgotten by readers of her story, subtitled An Ordinary Family’s Extraordinary Tale of Love, Loss, and Survival in the Congo.

Readers will come to know and care about Mama Koko and her extended family, they will grieve that family’s terrible struggles and tragic losses at the hands of the LRA, and they will realize the risks Shannon took to tell their story in hopes of garnering attention and help for the people she writes about and comes to love. They will also meet and appreciate Congolese expatriate Francisca Thelin with whom Shannon travels to Thelin’s devastated home country.

By weaving narratives of what life was like pre-LRA and what it has become now, Shannon skillfully reveals a tapestry of characters and personal narratives that are at once moving and frightful.

Once prosperous by local standards, Mama Koko, the matriarch, stays strong as her family loses everything and is driven into the bush with slim hopes of survival. But one by one her spouse, siblings, cousins, distant relatives, and their children become victims of unimaginable LRA cruelty.

Back in town, where everything including hope is sparse and people are barely hanging on, Shannon lives with Mama Koko and other survivors. She hears their stories. She films the people she interviews. She puts herself and Francisca in harm’s way more than once to capture what they are willing to share with her.

The question becomes, why? It’s a question Shannon asks herself. When a UN security officer asks, “Who are you with? What is your function?” she struggles to answer the question for herself. “It was weird enough in the U.S. answering endless questions about how I supported myself as a volunteer, the independent nature of my work. . . . The strangeness [in Congo] was exacerbated by the fact that I wasn’t sure I knew, even secretly, what my ‘function’ was.” It was a question that troubled Francisca the longer they remained in harm’s way, and it is likely to be one that troubles readers as well.

Why put yourself and others in terrible danger when you have no sponsor, no media assignment, no organizational support? What is the expected outcome, and how, specifically, might what you are doing help the victims of a long and vicious war that the governments of developed nations and their citizens care little about? The question creeps in: Is the author on an ego trip that asks too much of others?

The book jacket promises “compelling testimony to the strength of the human spirit and the beauty of human connection in the darkest of times” and it certainly delivers. But it also says that the book “explores what it means and requires to truly make a difference in an unjust and often violent world.”

Many readers are likely to ponder what difference Shannon’s adventure really made and whether the risks she subjected herself and others to was, in fact, sufficiently productive.

As one of Shannon’s subjects puts it, “What are you going to do with all of this [information]? What makes me so angry is that everybody who used to be in my district is dead. Some people come and they put you through a process, talk about the LRA incidents, but they are just collecting. It makes me wonder if you are for real.”

As she is leaving the Congo, Shannon recalls, “The question of the hour hung heavy around us. What now? I had already decided how I wanted all of this to end. . . . Francisca would emerge a leader for her country. I had no shortage of suggestions for [her] future leadership role, the one I had built up in my head—policy wonks to connect her with back home, campaign ideas, trips to DC to lobby Congress.”

Was there ever a more revealing picture of western interference, one wonders? But in the end, Shannon concludes, “It was too much for [Francisca] to even think about.”

“You have to let me do it my way,” Francisca tells her friend.

Years later, Shannon concludes, “Kony was still out there.” There were more deaths and greater shortages. “For the people of [Mamma Koko’s town] there are all the things that are gone, that will never come back.”

As for herself, Shannon writes, “When I think of Congo now, I push rewind, screeching backward, past the burnt grass like snow, the smoldering cinder huts, and the smoke still rising . . .”

Beautiful writing—but was it really worth the risk and the false hope that went with it?