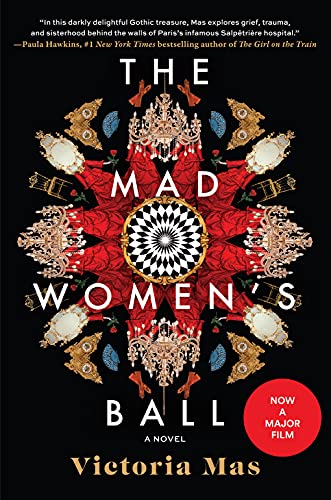

The Mad Women's Ball: A Novel

“A character study of one woman’s humanity and sacrifice.”

To the outside observer, the Salpêtrière Asylum, in 1885, is a place of miracles, where Dr. Charcot conducts his experiments in hypnosis to cure women of hysteria and other aspects of female madness. To the inhabitants, the place is either a refuge or a prison.

“The Salpêtrière is a dumping ground for women who disturb the peace. An asylum for those whose sensitivities do not tally with what is expected of them. A prison for women guilty of possessing an opinion. They say that the Salpêtrière has changed since the arrival of Professor Charcot twenty years ago, that only genuine hysterics are locked up nowadays. But despite such reassurances, the doubt persists.”

Eugénie Cléry is a young woman with ideas of her own and extremely outspoken. That irritates her father, but he does nothing because she’s still halfway obedient. It’s only when Eugénie makes the mistake of confiding in her grandmother that she can talk to ghosts that the seventeen year old finds herself hauled bodily to Salpêtrière. Eugénie’s brother Théophile, who accompanies his father on this odious journey afterward, curses himself as a coward for doing nothing to save his sister.

Geneviéve, a matron at the Salpêtrière, immediately recognizes that Eugénie shouldn’t be there, especially after the girl delivers her a message from her beloved deceased sister.

“In a fraction of a second, Geneviéve had crumbled. It must have been devastating for a woman determined not to be shaken by anything.”

She confronts the girl’s father.

“‘What do you expect us to do for your daughter?’

“‘To be perfectly honest, I have no expectation that she will recover. She is quite normal, except that, as I have explained, she claims to see the dead.’

“‘Why entrust you daughter to a psychiatric hospital if you do not expect her to be cured? This is not a prison. Here, we work toward treating our patients.’

“The lawyer thinks for a moment. He gets to his feet, picks up his top hat and brushes it vigorously.

“‘No one talks to the dead unless the devil is involved. I will not have such things under my roof. As far as I am concerned. I no longer have a daughter.’

“He gives Geneviéve a curt nod then stalks out of the office.”

Geneviéve decides she can’t allow Eugénie to be kept a prisoner in the hospital. Every year, the Salpêtrière holds the Lenten Ball, “offering patients some amusement and affording them some semblance of normality.”

In reality, the patients are paraded before outsiders who come to gawk and perhaps be entertained.

Geneviéve decides that during the Ball, Eugénie will disappear. She contacts Théophile, the only one showing remorse over his sister’s incarceration, and tells him her plans, and the boy, partly to atone for his cowardice as well as his concern for his sister, agrees to help.

Things won’t go quite as Geneviéve expects however, for if one patient flees the Salpêtrière, surely another must be expected to take her place, because only an insane woman would help another escape.

This is an interesting novel, translated from the French by Frank Wynne, giving an overview of the aspects of the treatment of women in France during the 19th century, when a woman might be declared insane and committed to an institution for merely being strong-willed enough to talk back to her husband. A great many conditions labeled “hysteria” found women thus unjustly imprisoned.

The usual horror stories of treatment of mental illnesses that other novels and the cinema have depicted are surprisingly absent with the relationship between matrons and patients, suggesting more of a dormitory-student-housemother arrangement than anything else. The doctors themselves are barely seen, with only one case of physician-patient maltreatment cited when a patient is raped by her physician during the Lenten Ball.

The conditions in the Salpêtrière, in fact, the novel, in general, appear fairly mild. There is very little conflict, with everything going according to plan: Geneviéve decides Eugénie will escape, and the girl does. No slip-ups, no hairbreadth evasions, no frantic chases.

With the help of matron Geneviéve, young Eugénie goes on to lead the life she should, while, in the irony of ironies, the matron returns to life at the hospital, only this time on the other side of the bars.

There is a bit of history, of both the hospital, its famous doctor, and one of its more famous patients, included within the novel, explained in footnotes, which may intrigue some readers enough to spur them to further research. With a theme that could have been a dramatic Gothic novel, The Mad Women’s Ball glosses over any sensationalism and opts for a character study of one woman’s humanity and sacrifice.