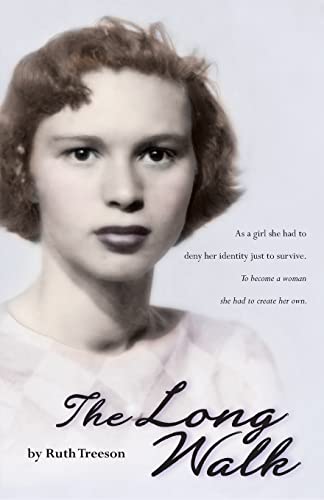

The Long Walk

This is the story of fifteen-year-old Rutka, a Polish girl orphaned by the Holocaust. Virtually all of her tight-knit Jewish family has been murdered. The tale begins at the end of the Holocaust, shortly after Rutka and her fellow concentration camp prisoners were released by German soldiers fleeing from the encroaching Allied armies. The narrative carries Rutka forward, with periodic recollections of her past, italicized for frame of reference.

An emaciated Rutka wakes up shivering one cold morning in a barn. A Russian soldier points toward a nearby town. Left on her own, with her family murdered, Rutka must venture forth into the world on her own, with no home, direction, plan, aid, or insight. She was a 15-year old girl left alone in a dark and mendacious world.

Rutka’s story unfolds as she recalls her early life in Warsaw. Descriptions of her warm family life are well formed and the narrative unfolds descriptively. In order to escape from the Warsaw ghetto, her family traveled to Krakow, where they lived until Nazis incarcerated the Jewish population. Like her Warsaw home, this home in Krakow also holds a place in Rutka’s heart.

Rutka and a girl named Rachel explore the remains of a destroyed Polish town, bereft of inhabitants. They discover a few meager scraps of food and find shelter in a deserted house, where Rutka takes a warm bath for the first time in ages. Such pittances of pleasure seem to be heaven-sent to the adolescent refugees. In the tub, Rutka attempts to scrub away the vestiges of an unspeakable horror. Yet, sharp memories of terror and the death of her loved ones cannot be washed away. They inhabit a stabbing place deep within her heart.

Rutka travels to Krakow, where she hopes to find any member of her family at home. Tormented by images of Nazi brutality, she struggles to adapt to her new freedom. Like so many other Holocaust survivors, she discovers someone else living in her home, a woman who sneers with displeasure upon discovering that the Jewish girl whose family lived there had returned. For the first time, Rutka understands that almost everyone she has known and loved is dead and that she has nowhere to live. Rutka has been orphaned by the Holocaust.

Rutka’s parents had placed her and her younger sister, Haniushka, with a Catholic convent when all seemed lost. Unfortunately, this surreptitious salvation was not long lasting. The Gestapo rewarded members of the community who turned in Jews. Alas, Rutka and her little sister, “Hanni,” were captured and sent to a concentration camp. In that camp, little Hanni is torn from Rutka’s hands and sent to the gas chamber. Rutka’s soul is deeply stained with guilt over this.

After her Krakow experience, Rutka is reunited with her aunt Genia, her mother’s sister. Painfully, she begins to accept that the rest of her family is dead. She has only her aunt and a few friends she had met at the convent. Through Aunt Genia, Rutka is taken to a “kibbutz” (communal farm) for surviving Jewish children. Here, Rutka explores a deeper sense of Judaism and she becomes a Zionist. With no country willing to take her in, Rutka prepares to enter the Palestinian territories illegally. She is resolute in her desire to help create a nascent Jewish state. Gradually, Rutka, Genia, and the other Holocaust survivors learn Hebrew, take on Hebrew names, and prepare for their entry into the Holy Land.

Shortly before departing for Palestine, Rutka learns that she can immigrate to America. She was sponsored by a Jewish family in Detroit that had just lost their teenage daughter. On the way, in New York, Rutka meets the only other surviving member of her family, her grandfather, who arrived in America before the Holocaust. Yet, he is too old and frail to care for Rutka. So she moves to Detroit and begins a new life in a new country. Forced to live with strangers and learn a new language, Rutka struggles to adapt.

America opened her arms to Rutka in the shape of Naomi and Irving Silverstein. Detroit held something that she desperately needed: stability. The Silversteins made Rutka feel at home and loved. In Michigan, she found the strength of will to focus on surviving and creating her future.

Rutka’s adjustment to America continued, with school, jobs and boyfriends. She learned how to fluently speak and write English and to adopt the customs of America. Eventually she moved to New York, where she settles into life, work, and a devotion to writing.

Despite many powerful factors that should have resulted in her death in a Nazi concentration camp, Rutka survives and prospers. As with so many other Jewish families during the Holocaust, she is the lone survivor. Yet being a survivor means victory. It means that Hitler’s goal of a world bereft of Jews would not occur. Within this victory is the sum total of Rutka’s young life, robust and filled with so much love. It is a life torn away by the fabric of intolerance. Smeared by the blood of blind hatred, Rutka discovers the strength of spirit necessary to ensure her survival. And, in doing so, she fulfills her part in the everlasting link of the survival of the Hebrew people.

The depth of brutality explored in The Long Walk is pale in comparison to other Holocaust novels. Although the book explores Rutka’s “long walk” after the end of the war, the reader is left wondering about details of life inside the Nazi concentration camp. Perhaps this book was designed for the young adult audience, in which case we can excuse the less than graphic depiction of life in a Nazi camp.

Treeson’s novel is filled with descriptive language and excellent dialog. The character of her protagonist is well developed. However, depth of character development in the surrounding individuals is not as well defined. This might be in keeping with the desired length of a contemporary novel. Yet the reader is left to wonder who these people that she loved really were. The rest of the book is marred only by the occasional typo, indentation failure, or conversation disconnect.

Repugnance, despair, and darkness exist within human nature. We learn nothing about ourselves if we do not examine this dark part of our psyche. Holocaust victims experienced incomprehensible brutality. Rutka’s “long walk” helps us overcome the evil of persecution and genocide, revealing the triumphant spirit of humankind.