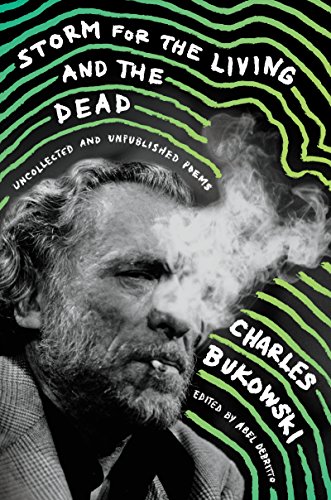

Storm for the Living and the Dead: Uncollected and Unpublished Poems

“Never mind that his art is almost always sexually themed, frequently violent, and often flawed. It is nonetheless art.”

Storm for the Living and the Dead might be remembered as the single work that best represents the full range—the unmasking, as it were—of Charles Bukowski’s oeuvre. This volume is filled with his nakedness, his verbal exposures, his need to be totally contemporary—to be seen as inventive—ergo his quest for candor and total revelation, the sheer gutsiness, in short, of his style and his vision.

Kudos to editor Abel Debritto for his skilled efforts. Storm for the Living and the Dead represents a remarkable job of sleuth work and a high degree of creative editing.

Debritto has uncovered, discovered, and in general searched out a full-length and fully rounded collection of Bukowski’s heretofore uncollected poems, some of which have been zine-published and some of which find their first publication in these pages.

Here is Bukowski again—as if he were still with us, hunched over his typewriter and cranking out his profane, wildly confessional, politically incorrect poems—the grand old man of the late 20th century zines, a whiskey sour in one hand and an explosive sheaf of poems in the other. This is the Bukowski who is always reading, always seeking to reconnect the hungers of both his imagination and his experience, always wanting more.

Bukowski writes about time and the end of time; he is obsessed not only with such horrors as nuclear holocaust but with the millions of individual disasters fate holds in store for us, just this side of some grand disaster.

Bukowski is, when the last match is struck, a romantic. Art and love provide his work with a dual prophylaxis against despair. Never mind that his art is almost always sexually themed, frequently violent, and often flawed. It is nonetheless art.

The poems in this volume convert easily from nostalgia on Bukowski’s part for his

early days and ways to a hope for new excitements and longed-for fulfillments, and in some instances, a frankly unadulterated desire for the perpetuation of the risk and passion of his characteristically wanton lifestyle.

Sex is Bukowski’s name for love, and there is nothing gentle about it. Art and love meld in these poems.

In “I think of Hemingway,” for example, Bukowski writes, “my typewriter no longer has/anything to say.//I will drink until morning/finds me in bed with the/biggest whore of them all:/myself.//”

Bukowski, having lived a quintessentially fragmented existence, acknowledges in these poems no commitment but to writing itself. His work is a call for independence in both thought and action, a reminder to the living that life goes on, ontologically and actually, that life is here for the taking, that life is asking, in fact, for the taking.

In the poem, “I was shit,” he adds, “animals love me as if I were a child crayoning/the edges of the world,/” Bukowski slipping artfully in this instance into the subjunctive borders between being and non-being, the solitary artist continually testing those ultimate barriers with his art.

In other words, “Dante, baby, the Inferno/is here now./and people still look at roses/” (“poem for Dante”).

Whether or not roses, those artfully-bred and artificially-propagated florals, can ever save anyone is not a question Bukowski answers—or even cares to ask.

“I’ve shown courage, drunkenness and/fear . . . ” he writes in “the conditions,” continuing in the romantic role of the solitary artist confronting the incomprehensible. Drunkenness always seems to help Bukowski, drunkenness and the dangling, signature cigarette trailing its beautiful and acrid 20th century smoke.

Bukowski uses his unfettered graphic intensities (drink, sex, etc.) to bolster many of these poems. These intensities, in fact, serve as his license to write, which he reasserts repeatedly throughout the volume.

In these pages, you encounter the arrogant Bukowski, the prolific Bukowski, and the Bukowski in pursuit of conquest, asserting supremacy over the world around him, at times exercising such a penchant for engagement that purpose itself becomes obscure, even lost.

In the poem, “being here,” Bukowski writes, “we are far too serious, we must learn to juggle/our heavens and our hells—the game is playing/us, we must play back./”

It’s hard to believe that Bukowski is not somewhere in the 34th latitude of infinity this very minute, kicked back and drinking fate under the table of the universe.

At some point, the game that’s “playing us” is over, “the curtain is down,/the seats are empty,/the watchman has suicided,/the lights are out,/nobody waits for Godot/.” (“he went for the windmills, yes”).

So what are we left with, a dead watchman, an empty theater, an existentialist play that doesn’t ever happen? But Bukowski happened, and he keeps on happening over and over again.

“Hell never stops it only pauses . . .//” writes Bukowski in “musings,” “this is a pause.//enjoy it while you can.//”

Everything is a pause. Everything is the tissue-thin, yet nonetheless impermeable, borderline-membrane between infinity and/or disaster. And yet there is sex. And yet there is love. And yet there is art.

Given all that, in “song for this softly-sweeping sorrow . . . ,”Bukowski says, “let’s light lights/let’s suffer in the grand style—/toothpick in mouth, grinning./we can do it./”

And we can. We can do it. We can pour ourselves a straight shot or two and step directly into the sad, ecstatic, sometimes depraved, but always unforgettable world of Charles Bukowski, particularly as it is unfolded in this gritty, passionate, and memorable collection.