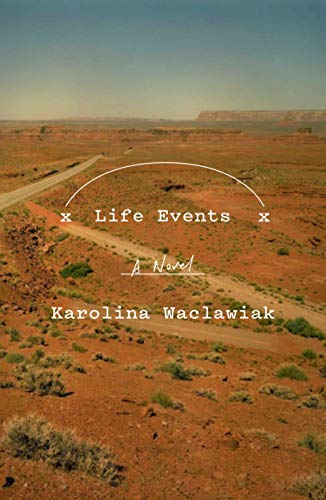

Life Events: A Novel

“Karolina Waclawiak is no mere writer. She is a master of painting emotions with many different colors.”

Evelyn, the main character of this novel, is nothing if not self-absorbed, which is not so surprising given the Instagram era we are forced to live in. Evelyn is 37 years old as the story unfolds, and she’s grappling with that most mundane of mid-life crises: a breakup with her husband Bobby whom she feels is not a good match for her soul.

The truth is that Bobby is not all that unhappy with Evelyn’s decision to break up because he can’t seem to connect to her either and in short order, he is dating someone else.

Evelyn’s transition is nowhere near that smooth. Even though she is a fierce navel gazer, she just cannot seem to connect to herself. Where to turn? Evelyn cashes in her 401K money so she can spend some time finding herself, and this is where the book takes off.

Evelyn joins a group of like-minded souls who are training to be “exit guides,” aides who assist those with terminal diseases who want to meet their maker on their own terms. The training, as described, feels very much like an Alcohol Anonymous meeting, at least as Waclawiak describes that first meeting:

“We were of varying ages in this room, but it felt like we had all somehow misjudged the big life events. We were focused on the end because we had already fucked up the middle part. We were flailing. Or maybe just I was flailing. People in the world were filling their social media feeds with momentous life change like weddings and babies and new, serous jobs, and though some people in this room might have been doing just that, too, I was not. I had hit a point of stagnation, and I felt like I was dying.”

When she gets home (she’s still with Bobby at this point), her soon-to-be-ex compares what she’s doing to her latest fad.

“I feel like you start something new every week. A beading workshop. Spin class.”

“That’s vaguely insulting,” she says.

And she right of course which is one of the myriad reasons the split soon takes place.

Whatever Bobby thinks of the group, Evelyn’s trip down this odd career path (which feels like it might actually exist or will in the near future) elevates the book above other novels of this sort. Soon Evelyn is interacting with head trainer Bethanny and other rising death doulas.

It’s no surprise that she’s attracted to a fellow exit guide trainee, but she remains a bit frightened of him as well since he’s her first potential lover since her husband. Truth is, Evelyn seems a bit frightened of everyone be they fellow guides or the “clients” who are dying.

A woman named Daphne is Evelyn’s first client and she asks Evelyn, on the sly, to take her to a former dive bar where she brags about all the fun she used to have in the bar’s rest room. It’s a touching reference because it reminds Evelyn and us that even the dying were once living it up,. But the present is, as they say, ever present. As Daphne and Evelyn prepare to leave, Evelyn collapses from her illness, and both women are cruelly reminded why they even know each other.

And then there are the male clients Evelyn must treat as well, and there is a much different dynamic present, the one you might expect when men and women find themselves alone in a highly charged atmosphere. A former pornographer puts Evelyn’s hand on his genitals, and she tells him it’s okay. There is another randy guy who is dying. Evelyn finds him so attractive and vibrant that she has sex with him. Evelyn can see she’s headed for a world with no boundaries and abruptly quits the exit guide program.

She retreats to the desert to ruminate on her life, to try to understand her dying alcoholic father and her mother and the choices all of them made. She goes deeper and deeper into the desert, visiting ghost towns in search of herself until she winds up in Death Valley.

She thinks about what a therapist once told her about there being only two types of “emotional disasters” that get imprinted on children. One tells a child “you are bad” while the other leaves the child with a feeling of “you are no one.”

Evelyn feels she is no one. In the hands of a less polished writer, this novel might be one long cliché, but Karolina Waclawiak is no mere writer. She is a master of painting emotions with many different colors. Consider Evelyn’s thoughts in the desert as she hears a far-off plane overhead:

“I once again had the feeling of I am no one well up inside of me. As I looked up at the jet hanging low overhead, I wanted to plane to see me. So I took a few steps and reclined on the mud that had cracked into near-perfect squares and stared up at the plane and the sky. ‘Can you see me?’ I wanted to call out. But I didn’t. Because I wanted to be seen, and not seen at all.”