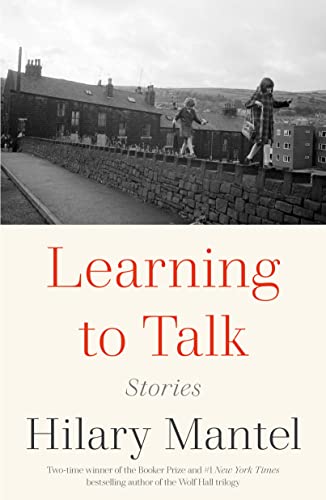

Learning to Talk: Stories

Hilary Mantel is best known in America as the author of the historical trilogy, Wolf Hall, Bring up the Bodies, and The Mirror & The Light. A convincing entry into the world of 15th and 16th century England, with a particular focus on the life and death of Thomas Cromwell, it displays mastery both of substance and style, making the strange familiar. The writer’s eye for period detail and her ear for the then-current speech earned her, twice (in 2009 and 2012), the Man Booker Prize.

But she has also published works of fiction and nonfiction that make the familiar—our modern world—strange. In Learning to Talk, her new collection of old stories, Mantel manages to describe life in an insular village in northern England in the 1950s as if it too were history and, even in its trivia, not to be trifled with. Although this effort is more modest than that of the great trilogy, there’s the sense of a lost place and time recaptured here as well.

The six stories that comprise Learning to Talk have all been published before, beginning with “King Billy is a Gentleman” in 1992 and ending with “Curved is the Line of Beauty” (2002). In addition to the title story (1987), we have “Destroyed” (1998), “Third Floor Rising” (2000), and “The Clean Slate” (2001). This edition has been book-ended with an authorial Preface and a kind of Postscript, “Giving Up the Ghost,” which is a précis of her full-length memoir of the same name published in 2003. Fludd, her 1989 novel about the village of Fetherhoughton, covers much the same terrain. But Learning to Talk is more than a repackaging of previously published prose; there’s a through-line to the narrative which provides a sequential arrangement, and a portrait emerges of the author that’s rounded if oblique.

As Mantel explains, in the opening lines of her Preface: “These stories are about childhood and youth. They were pulled together over a period of many years; I choose that strenuous verb because, for me, the process of short fiction is full of tension and resistance.” Further, “All the tales arose out of questions I asked myself about my early years. I cannot say that by sliding my life into a fictional form I was solving puzzles—but at least I was pushing the pieces about.” The “pushed-about” pieces describe a penurious life, a sickly and secretive child, an upward-aspiring mother with two men in the house. This makes for a pinched narrative; there are dogs to walk and younger brothers to torment and plums to suck and shoes to buy but little human warmth. It’s almost always raining and almost always cold.

Predictably, as well, there’s a deal of mordant wit. “So far, so good: what sort of family do you expect me to come from? All-singing, all-dancing? You’d just know they’d be tubercular, probably syphilitic, certifiably insane, dyslexic, paralytic, circumcised, circumscribed, victims of bad pickers in identity parades, mangled in industrial machinery, decapitated by forklift trucks, dental cripples, sodomites, sent blind by measles, riddled with asbestos and domiciled downwind of Chernobyl.”

This pretty much describes the cast of characters we meet in Learning to Talk. As the years and tales proceed, the narrator—at 11—departs the industrial hamlet with her mother and her mother’s lover, leaving her father behind. “The village of Derwent began to sink beneath the water in the winter of 1943.” School is a trial. People in the town they move to are strait-laced and censorious; the girl prefers her privacy to friendship, though in “Curved is the Line of Beauty,” she and a friend named Tabby trespass “on the wrecks” of cars and get, for an hour, lost. Mostly, however, the narrator’s alone: resistant to but calmly annotating the behavior of her peers. A handful of characters earn her compassion, the majority her scorn.

Here is the organizing principle of Mantel’s fictive procedure: “I distrust anecdote. I like to understand history through figures and percentages of these figures, through knowing the price of coal and the price of corn, and the price of a loaf in Paris on the day the Bastille fell. I like to be free, so far as I can, from the tyranny of interpretation.”

Further, “The story of my own childhood is a complicated sentence that I am always trying to finish, to finish and put behind me. It resists finishing, and partly this is because words are not enough; my early world was synesthetic, and I am haunted by the ghosts of my own sense impressions, which reemerge when I try to write, and shiver between the lines.”

There are many lines one wants, while shivering, to quote. Here are a few: “It seemed indecent to look at him. In that one moment it seemed to me that the world was blighted, and that every adult throat bubbled, like a garbage pail in August, with the syrup of rotting lies.” Or, “There was air in the spaces between my bones, smoke between my ribs. Pavements hurt my feet. Salt sought out ulcers in my tongue. I was given to prodigious vomiting for no reason.” Or, of a store where the narrator’s mother once worked, “It was taken over by pornographers, and those kinds of traders who sell plastic laundry baskets, dodgy electric fires and molded Christmas novelties such as bouncing mince pies and whistling seraphim.”

Few contemporary authors have so stern and spare an aesthetic, even when the language grows —as in these quotations—ornate. What Mantel provides in Learning to Talk is a vision of constricted life that enlarges on close viewing. Thomas Cromwell—that gimlet-eyed witness to human ambition and folly in the 16th century—would find an inheritor here.