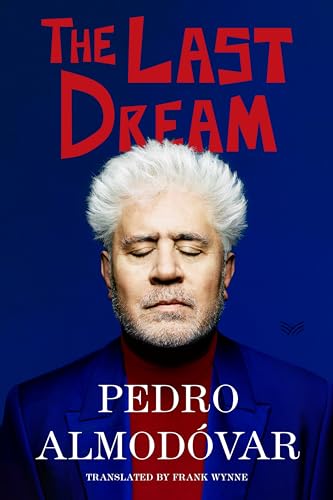

The Last Dream

“The legion of admirers of Pedro Almodóvar’s brilliant films will find The Last Dream an interesting supplement to his body of cinematic work.”

Over the past half century, Pedro Almodóvar has written and directed 23 films that are celebrated as international classics. His career began just as Spain was moving toward a democracy after the death of dictator Francisco Franco. Almodóvar’s early films, with openly gay characters, sexually liberated women, and transexuals celebrated a new, free Spain.

As he grew older, his films became more reflective. They always demonstrated his love for the sort of melodrama that was evident in American “women’s pictures” of the studio era, combined with a wicked sense of humor. Visually, they are known for the brilliant colors of their settings costumes, and lipstick. Like Ingmar Bergman and Federico Fellini, Almodóvar developed a stock company of actors he used repeatedly in his films, including Carmen Maura, Penelope Cruz, and Antonio Banderas.

Some version of Almodóvar the auteur is visible in many of his films. Law of Desire (1987) is about a controlling, self-absorbed gay writer-director. Pain and Glory (2019) centers on an aging writer-director, suffering from various health issues, looking back on past relationships. Yet the auteur claims at the outset of his new book, The Last Dream, to have no desire to write an autobiography or be the subject of a biography: “I have always been somewhat resistant to the idea of a book entirely about me as an individual.” Instead, he has published a collection of 12 short pieces (some stories, some essays), written from the late 1960s to the present, that have been deftly translated by Frank Wynne. Though the volume will have great interest for Almodóvar aficionados, nothing here is of the interest or artistic merit of Almodóvar’s films.

Occasionally we get a useful reflection on the auteur’s life. With characteristic perversity, he ends the volume with a sentence that would be a perfect opening for an autobiography: “I was born in the early 1950s, a terrible period for the people of Spain, but a glorious time for cinema and fashion.”

In the introduction, he writes of the three places that formed him as a person and as an artist: “the courtyards of LaMancha, where women made bobbin lace, sang, and bitched about everyone in town; the explosive and utterly free nights in Madrid between 1977 and 1990; and the tenebrous religious education I received from the Salesian brothers in the 1960s.”

The title story, “The Last Dream,” is a tribute to his mother (motherhood is a major theme in his films), who taught him that “reality must be complemented by fiction to make life easier.” In one of the essays, Almodóvar’s reflections on his loneliness echo the state of his alter-egos in his films: “I have come to this place of almost total isolation as a result of not replying to others, of not having worked on genuine friendships or neglecting the ones that I had.”

Almodóvar’s fascination with Catholicism comes to the fore in his most interesting stories, all of which celebrate pleasures of the flesh over Catholic austerity. In one, a voluptuously dressed young woman confronts the headmaster of a Catholic school about his brother’s experiences in an institution where the priests had orgies and took sexual advantage of the boys in their charge. The priests preached repression, but their private rites were Dionysian. When the woman confronts the headmaster with his own desire for her brother, the old priest stabs her, only to find that she was the boy who was the object of his desire.

In another story, “The Mirror Ceremony,” Brother Benito becomes fascinated with an aristocratic novitiate. When the new monk admits to being a vampire, Brother Benito begs to become a vampire himself. He, too, wants to lose his reflection. For Almodóvar, the drinking of Christ’s blood in the Eucharist is itself a form of vampirism.

In “Redemption,” Christ’s sharing of a prison cell—and his body—with the thief Barabbas leads him to fully understand and embrace his humanity. Man’s hate, fear, and love are superior to the “tranquil and unvarying dream,” Christ has experienced before. Barabbas, too, is changed by the love he feels for Christ. In “Joanna, the Beautiful Madwoman,” a fanciful elaboration of Sleeping Beauty, the voice of God counsels a devout queen who has engaged in acts of penance to try to awaken her sleeping daughter, to wake her with “secular, boisterous, traditional, violent feasts.”

“Too Many Gender Swaps” is the saga of a director’s principal actor and lover, León, insisting on starring in gender-swapped versions of Jean Cocteau’s La Voix Humaine, Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire, and John Cassavetes’ film, Opening Night, three works that play important roles in many of Almodóvar’s films.

Later essays reflect the melancholy one feels in recent films like Pain and Glory, where the sense of sadness and isolation is turned into great art.

The legion of admirers of Pedro Almodóvar’s brilliant films will find The Last Dream an interesting supplement to his body of cinematic work. However, his greatest artistry is on the screen.