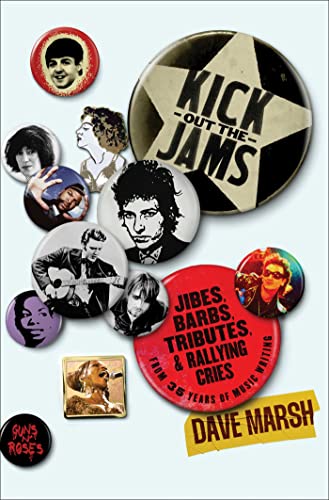

Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes, and Rallying Cries from 25 Years of Music Writing

“Improbably, perhaps, for a work of music criticism, Kick Out the Jams is as revealing a first draft of history from those cumulatively calamitous three-and-a-half decades as you’re likely to find anywhere.”

At a summer 2017 book launch event for Daniel Wolff’s Grown-Up Anger: The Connected Mysteries of Bob Dylan, Woody Guthrie, and the Calumet Massacre of 1913, Wolff shared the stage with his friend and colleague Dave Marsh, who by then was known to refer to himself as “the Methuselah of rock critics” (perhaps an ironic designation for a writer who counts a book titled Before I Get Old—the definitive history of The Who—among his best known works).

Following Wolff’s and Marsh’s remarks, as a spirited question-and-answer session kicked in, a 60-ish couple stepped together to the microphone and earnestly thanked Marsh for his two landmark Bruce Springsteen biographies, Born to Run (1979) and Glory Days (1987). Then they lauded both Marsh and Springsteen (but especially Springsteen) for their lifelong commitment to progressive ideals. Anyone in the room who knew Marsh’s work beyond those two books also knew he was about to ruin their night.

“Bruce Springsteen, progressive?” Marsh scoffed. “No. Moral? Absolutely. If Bruce were truly progressive, he never would have stumped for that corporatist centrist Barack Obama.” The mortified couple quickly gathered their belongings and slipped out of the venue.

Those familiar with the breadth of Dave Marsh’s work know the deep, thoughtful, and genuine humanity that runs through all of it, but they also know Marsh’s unwavering aversion to conceding any point that matters. While reading the remarkable new anthology of Marsh’s work, Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes, and Rallying Cries from 35 Years of Music Writing—co-edited by Wolff and music journalist Danny Alexander—one is struck again and again by his unflinching sense of mission, whether Marsh is writing about Springsteen or Elvis or Kurt Cobain or his beloved MC5, or delivering unimpeachable, scorched-earth jeremiads against the RIAA, the PMRC, Ronald Reagan, Al Gore, either George Bush, or that strangest of Bush II bedfellows Paul “Bono” Hewson.

It’s never been just about the music with Dave Marsh, from his early days with Creem and Rolling Stone to the more overtly political Rock and Rap Confidential, which Marsh co-founded in 1982 (the first year covered in Kick Out the Jams’ 35-year span). But when he digs deep into the music, as in stunning pieces on gospel singer Dorothy Love Coates, singer-songwriter Patty Griffin, or the late, lamented Dylan interpreter for the ages Jimmy LaFave, the precision and perceptiveness of Marsh’s writing and its uncanny ability to make a reader feel like they’ve grown new ears remain unequaled.

But even when Marsh is focused the most on music, his work is never just about the music. As Marsh writes in a mesmerizing and typically expansive and illuminating piece on Coates: “Dorothy Love Coates recorded perhaps her most piercing, mesmerizing song, ‘The Strange Man,’ in the spring of ’68, about the time that Dylan was making The Basement Tapes and John Wesley Harding. Coates’s gospel matches any dream of St. Augustine or wheels-on-fire vision. And in its attempt to exorcise the catastrophe of the end of Dr. King’s dream and, at the same time, hold on to the possibility of grace and salvation, it ranks among the great acts of faith set to music.”

Like all of Marsh’s work dating back at least as far as his unforgettable contribution to Greil Marcus’s 1978 anthology Stranded: Rock ’n’ Roll for a Desert Island (Marsh submitted a playlist titled “Onan’s Greatest Hits”), his writing has always had its laugh-out-loud moments, even when that humorous tone underscores a more sobering point. Along with Born to Run, The Heart of Rock ’n’ Soul: The 1,001 Greatest Singles Ever Made, is arguably Marsh’s best-known and best-loved book; more than Stranded or Marsh’s contribution to it, The Heart of Rock ’n’ Soul is the ultimate desert island read, with the proviso that it be accompanied by a turntable and a crate of 45RPM records—the essential guidebook for a journey into those records’ unfathomable depths.

By contrast, Kick Out the Jams would serve admirably as a poignant back-to-the-world primer, a useful answer to anyone lost at sea from 1982 to 2017 who might reasonably ask what they missed. Improbably, perhaps, for a work of music criticism, Kick Out the Jams is as revealing a first draft of history from those cumulatively calamitous three-and-a-half decades as you’re likely to find anywhere.

Consider the prescience of its first entry, “Elvis: The New Deal Origins of Rock ’n’ Roll,” published in December 1982, on what Reaganism would cost the country (and its convincing and career-defining articulation of why such topics belong in music magazines).

Or take Marsh’s one-line distillation of the insulting and disingenuous 1984 column George Will wrote after attending half a Bruce Springsteen concert, which chided the laboring masses for failing to match the exuberance of Springsteen “and his merry band”: “In other words,” Marsh writes, “if you find slapping bumpers onto compact cars less fulfilling than singing rock & roll songs in front of adoring masses, fuck off.”

“Suicide Notes,” Marsh’s staggering and deeply considered reflection on Nirvana lead singer Kurt Cobain’s June 1994 death, incorporates a capsule history of punk’s Situationist ethos and the complex origins and implications of the “cult of authenticity” in rock ’n’ roll (among many other things). Considering how much ink was spilled on Cobain’s death in the mid-’90s, Marsh’s essay will be far from the first meditation on the Nirvana singer’s death consumed by anyone drawn to Kick Out the Jams. But it might as well be the last. Pulling a single quote from this essay could do nothing but reduce the scope of what it conveys. “Suicide Notes” might be the best single piece of writing Dave Marsh has ever done, and it alone justifies Kick Out the Jams’ price of admission.

Marsh is at his most deliciously uncompromising in another obituary-and-then-some, “Lamentation for a Punk,” perhaps the last take on Frank Sinatra’s 1998 death you ever expected to read. Reacting to a cultural moment when it reeked of blasphemy to call Sinatra not just a great singer, but “the greatest,” Marsh writes, “Sinatra was in a sense the model for the Angry White American Man. More than anything else, this accounts for his alliance with Nixon and later that ultimate enemy of tolerance and equality, Reagan—and for his loathing of women as public figures, and his hatred of the media (which 95 percent of the time kissed his ass, just as it kisses the ass of most of the Angry White American Men who complain about it most avidly, from Rush Limbaugh on up to actual humans). The beginning of Sinatra slipping into this symbolic role came in the mid-1950s, when he became part of the effort (I am tempted to say ‘plot’) by the Tin Pan Alley establishment, led by the ASCAP songwriters (who barred virtually all Black and working-class songwriters), to discredit the new musical synthesis [rock ’n’ roll] by claiming it was the pure product of payola and other forms of bribery and chicanery.”

Marsh writes about race incisively and unsparingly throughout Kick Out the Jams, drawing the railroading of the Central Park Five powerfully into a 2002 piece reacting to the death of Run DMC’s Jam Master Jay and the NYPD’s and mainstream media’s determination to leverage the tragedy to criminalize hip-hop culture.

A piece from the following year celebrating the life and contributions of the recently departed Nina Simone eloquently explains why Marsh describes the nearly impossible-to-categorize Simone as a “freedom singer”: “The term describes her militant presence in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the way that she sang, both within and without the limits of predictable cadence and melody. More than that, it describes what she sought. Like her good friends James Baldwin and Lorraine Hansberry, Nina Simone made art about wanting to live like a free person. This certainly didn’t mean to live—or to sing—like a white person or, for that matter, an American. It meant living, and singing, like a person who not only counted on the promise but lived in the actuality of the American Dream.”

In Kick Out the Jams Marsh also mourns a far more personal loss, that of his daughter Kristen Ann Carr, to whom he movingly pays tribute. Following her 1993 death at age 22 of a rare sarcoma, Marsh often said he could no longer write about Bruce Springsteen, because the Springsteens’ immense support for Marsh’s family and the foundation they built in her name had made it impossible to write about the Boss with any semblance of objectivity. (Fortunately, Marsh breaks that vow in a monumental essay on Springsteen’s 2012 album Wrecking Ball, co-authored with Kick Out the Jams co-editor Danny Alexander.)

The fact that Texan singer-songwriter Jimmy LaFave was also facing death from sarcoma as Marsh told his story in a 2017 Austin Chronicle article, “Jimmy LaFave in the Present Tense,” makes the book’s concluding piece all the more moving and wrenching.

As Marsh admits in one of many personally revealing moments in Kick Out the Jams, “I’ve always loved being a critic, but like any writer, in my heart I’m a storyteller.” Kick Out the Jams tells the story of our times and his, rarely in a way we’ve heard it before, and never in a way that’s easy to hear it, but always in the way it must be told.