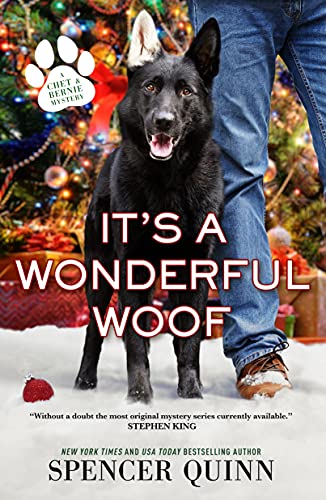

It's a Wonderful Woof (A Chet & Bernie Mystery, 12)

“Writing from an animal’s point of view cannot be a simple thing to do, but Quinn seems to have nailed it. It would be hard to imagine this story from any human perspective.”

Chet and Bernie Little, partners in the Little Detective Agency, are back and in rare form. Bernie is the human part of this duo, while Chet is the German Shepherd mix—black with one white ear—and we learn about their adventures through Chet’s point of view.

To say this is unusual is perhaps an understatement, but by the first page, the reader fully accepts who the narrator is, what he understands, and how he expresses their adventure for our understanding.

The story begins with Bernie and Chet leaving a Christmas party, only to encounter a mugging—one very big man beating up one very little man. Bernie just doesn’t like this, and the melée begins!

From Chet’s perspective, “Oh dear. That was my thought at the moment. Not ‘Oh dear’ on account of Bernie being in trouble . . . But . . . more about disappointment to the big guy’s technique. . . . Bernie’s . . . sweet uppercut . . . Click! Right on the point of a too-large chin. Then came the part I love the best, how speedily Bernie’s fist gets back to the starting position, just as speedy as needed . . . and all of a sudden I understood what humans meant when they were having an up and down kind of day! Wow! You could learn so much in this life just by being there.”

Thus the reader is drawn into Chet’s mind from the very beginning and never leaves it for the rest of the book.

The little guy, the victim of the mugging, turns out to be another detective acquaintance of Bernie’s, Victor Klovsky. Now, Victor is not the best detective in the world, but he is a good researcher, and several pages later when Bernie is approached by Lauritz Vogner to take on a job requiring a lot of research, something tells him to turn it down; he recommends Victor in his place.

When Lauritz laughs at Bernie’s rejection, Chet sees Lauritz from another angle, “Lauritz laughed for what seemed like a long time. Human laughter is usually one of their best sounds, but this particular laugh seemed a bit unpleasant, and maybe even unfriendly, like Lauritz was not actually liking Bernie. How could anyone not like Bernie? It made no sense.”

Lauritz leaves, Chet and Bernie move on with their holiday celebrations, and all is quiet until Bernie gets a call from Victor’s mother. It seems that Victor has disappeared, and Bernie has a queasy feeling that Lauritz may be involved.

And the story unfolds with Chet and Bernie beginning their search. Clues take them to an old church, no longer functioning as such, now an archeological dig site. The history of the church is somewhat murky, add to that a supposed curse, and Chet’s detection of snakes . . . lots and lots of snakes.

As the investigation progresses, it becomes apparent that Victor may have stumbled onto some very deep research leading to a 16th century piece of art by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, and Bernie worries that this research might have cost Victor his life.

Quinn is very good at creating characters in a variety of molds: old, young, vulnerable, academic, brilliant, and nasty, just to throw in a few adjectives. But as each of Quinn’s characters come into Bernie and Chet’s view, each has something to offer in the search for Victor.

In this character development, Quinn is very good at leading the reader to believe that some characters are one thing, but turn out to be not exactly what first impressions indicate, and only Bernie and Chet can discover the nuances of their personalities.

It doesn’t take long for a few bodies to start piling up, adding to the complex search for Victor, as well as a valuable Caravaggio painting that many people want to get their hands on at any cost!

The requisite denouement scene is well laid out with a nail-biting finale.

This is not the first Chet and Bernie adventure, and any fans already familiar with this team accept Chet as the narrator and actually look forward to his sometimes wandering thoughts—food, past experiences, other animals, human relationships—before he comes back to the point at hand and lays out a clue or two.

Although a mystery with some nastiness folded in, Chet keeps the reader informed, and only when necessary does he share his sense of anger, curiosity, and resolution for the event at hand.

Writing from an animal’s point of view cannot be a simple thing to do, but Quinn seems to have nailed it. It would be hard to imagine this story from any human perspective.