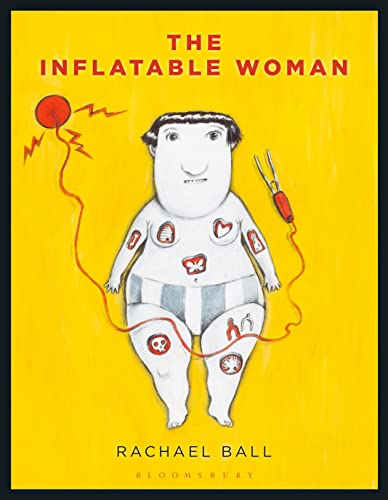

The Inflatable Woman

Rachel Ball’s graphic novel The Inflatable Woman is unlike any cancer memoir currently published in its creativity and fictionalized account told through the main character Iris, who stands in for Ball and her experiences.

Iris discovers lumps in her breast and proactively seeks medical attention only to hear the worst—that it is breast cancer; she will require a mastectomy as well as rounds of chemotherapy and radiation. A zookeeper by day, Iris is cheered on by a cast of loving animals, including serenading penguins who get into philosophical debates, Grandma Suggs, and coworker Maud. By night, however, Iris is a prima ballerina, at least online and in the fantastical emails she crafts and sends her online lover Henry, who claims to be a lighthouse keeper. Whether or not Henry is as he says is up to the reader to determine given that Iris is not who she says she is, either.

A woman filled with fear and loneliness, not just in dealing with cancer but in reflecting on her life, Iris eventually joins a support group of other cancer survivors and begins to put the pieces of her past behind her and plan her fearless future where she is truly the star instead of only imagining being one.

Empathetic readers will feel Iris’s pain and depression so beautifully illustrated in the black and white images of the book. On primarily black paper, the art itself acts as a white light or beacon through the darkest of times for both the author and her avatar.

The Inflatable Woman is not as prosaic as to act as a cheerleader to those with breast cancer or make some grand claim about relationships, rather it is a personal memoir mixed with fiction that illustrates the complexity of love’s yearning and a life unlived, whether due to fear or opportunity. While Iris does claim that cancer changed her life, it is not surprising any more than it is a common trope of cancer memoirs—cancer always changes a life, how can it not? From new daily routines to a different physical form, cancer interrupts and alters.

It is unfortunate, however, that more attention wasn’t given to Iris’s loneliness or her desperation for Henry’s love. Understanding what motivated Iris to lie and then to accept that after meeting once that he would a) believe she was a prima ballerina and b) have readers consider that Henry would think that squat and slightly dumpy Iris was a ballerina capable of pas de deux is a bit ludicrous.

Also, it would have been nice to understand why Iris would think that just a few weeks of communication with someone who had no other name other than his internet handle that she would be in love or that he would feel the same. And why on earth would she go so far to buy a wedding dress after a first meeting when neither of them shared any sort of romantic acknowledgement of feelings or mentioned anything else. Further attention to building Iris as a character would have created stronger engagement in this fast-paced story. As it stands, Iris sounds like a foolish teenage girl who remarkably isn’t caught in her own web of lies to a man she thinks she loves after only one meeting.

Filled with unique illustration, poetry, lines of fiction, the mundane and the surreal, as well as magical (what else would talking penguins or polite monkeys be if not magical or surreal?), Rachel Ball is sure to capture fans with this debut despite the drawback of a not fully fleshed out protagonist.