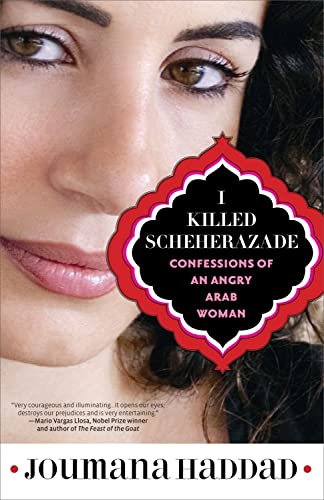

I Killed Scheherazade: Confessions of an Angry Arab Woman

“An astute, vigorous, and candid participant-observer who seeks to radicalize the conditions by which Arab men and women can find satisfying, secular, and sensible lives together.”

This spirited polemic combines “confessions of an angry Arab woman” with her reflections on the plight of men as well as women trapped in a schizophrenic realm. Founder of Jasad (“body”), an erotic magazine written in Arabic, Joumana Haddad seeks to correct the distortions that warp both Muslim and Western views of her sisters. She aspires toward “both a testimony and a meditation” on what Arab womanhood means and could mean.

She tries to achieve this by shifting away from a rant, an autobiography, or “the escapist allegories of a novel.” Keen to pay attention to the blossoming forest of possibility for women rather than the superficial, sensational sound of a tree falling (or a media-hyped factoid from the Muslim world), she urges us, citing this proverb, to listen “to the whispering of a growing tree.”

Forty years old, Ms. Haddad grew up during the Lebanese war that destroyed her hometown. She begins this brief account by recounting her childhood, when at 12 she opened Justine by the Marquis de Sade. This and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita inspired her to take up taboos and to break convention. Her skepticism as she came of age amid chaos soured her on the surety of any absolutes.

Instead, she created erotic poetry. She wryly notes how the average Arab reads a quarter of a page a year, and how one-half of one percent of the Arab audience turns to verse for pleasurable fare. She quotes (the book is full of wonderful borrowings) George Bataille: “There is only one of two possible options: either the Word drains Eroticism, or Eroticism drains the Word.” Ms. Haddad’s bilingual upbringing through French allows her to navigate wider literary waters than her Beirut existence afforded her; her own Christian background (she does not dwell on this much, however) also places her in a complicated position regarding her homeland. She appears to live in its capital city without loving it.

Therefore, she nods to Zaha Hadid’s “No matter how much progress has been made, there is still a world that for women is taboo. And in that world lies her freedom.” Ms. Haddad seeks liberation through her magazine and in her poetry, but also in her desire to overcome prejudice while rejoicing in a liberation that allows her to be as feminine as she feels. She attacks the sexist system, quoting Elfriede Jelinek, but not men themselves.

Ms. Haddad affirms that egalitarianism is not a demand, but an assertion that every woman must feel free to make. For her scheme of transformation, a woman needs to relegate sexual activity to the same niche where religious expression should be enacted. That is, in private.

As she elaborates: “In order to have, we need to give: so enough of religious exhibitionism/ voyeurism, in all its forms. Praying should be like making love: a private matter. Everybody speaks of sexual obscenity, but almost nobody speaks of religious obscenity. Those who make love in public are sent to prison: it is maintained that it constitutes an offense against public decency. I dream of a secular, uncontaminated world, where the same treatment is reserved to those who transform their religious convictions into a carnival.”

Ultimately, she fulminates against those who try to keep her and her sisters tethered. She calls Arab women “funambulists,” that is, “hanging in the air, between the sky and the earth, on a cord stretched between misery and deliverance. Moreover, there’s no safety net under us.”

Ms. Haddad does not comment much on her life as a mother, in terms of her two sons; we learn nothing about her relationships or her own erotic or sexual predilections. This lack of detail, extended to what we do not learn about her past or present partners, surprises. Her allusions, which dart away from candor, remain her right, but they lead the reader to wonder if some of this escape “from the narrow egocentrism of a systematic autobiography” is a bait and switch, given her prominent proclamations of sexual revolution and erotic rebellion.

Moreover, she tends to preen or pout about the reception of her magazine. This undermines her bold message. More emphasis upon her magazine’s content would have proven more convincing. How and why does Jasad matter? Her pride in its launch is understandable, but for foreign audiences unable to read its contents, how its provocations have accelerated her campaign to achieve liberation deserves coverage very much lacking here.

She aims to release this set of reflections and resolutions rapidly, it appears. She writes as if under pressure to meet a deadline, although I am left wondering why her hurry. This thin book does not deliver an in-depth exploration of sexuality, motherhood, the clash of Christian and Muslim beliefs about how women are to be controlled in the Middle East, or her efforts at bridging the gaps between cultures by her fluency in French as well as Arabic. (This version has no translator credited in the galley proof, so I am assuming she writes also in pithy, punchy English.)

Expansion of these essential topics certainly would have added value to this small work, if making it a larger one. She remarks late on in this brief manifesto that “I’m not ready for these topics yet.” This is her prerogative, of course, but the spicy if scanty results serve more to stimulate the reader’s appetite for a main course served by her from such intriguing ingredients. She sprinkles after her chapters one poem as a sample of her style: tellingly, an “attempt at an autobiography.” Perhaps soon she will deliver such a work in prose.

However, this is more a manifesto and series of short reflections than it is, as she warned, a straightforward chronicle of her entry into maturity and confidence. The promotional material for this English-language rendition boasts that Ms. Haddad is dubbed “the Carrie Bradshaw of Beirut,” but especially after the Orientalist and consumerist second installment of Sex in the City, such a role model appears unwisely chosen. This facile comparison slights the talents of an astute, vigorous, and candid participant-observer who seeks to radicalize the conditions by which Arab men and women can find satisfying, secular, and sensible lives together.

Eschewing sensationalism or prurience, she tries instead to speak--if hurriedly and with great animation--to an audience accustomed to see Arab women as veiled and prominent or as unveiled and invisible to Western eyes. She dashes away before she can be categorized, catalogued, or cornered. Ms. Haddad confounds our cultural reactions. She foils, too, one’s expectations. This stance results in a subtler exposé than the marketing of this testimony may let on but perhaps its shape-shifting nature leads into her own labyrinth, representing the complexity of Arab femininity.

She concludes her tale with a litany of how she killed Scheherazade of the 1.001 tales. Her character proved dangerous, “a sweet gal with a huge imagination and good negotiation skills.” So Ms. Haddad strangles her, even as the fictional femme pleads for one last story. Ms. Haddad favors resistance and rebellion, for submission and compromise, she reasons, render neither women nor men any lasting favors.