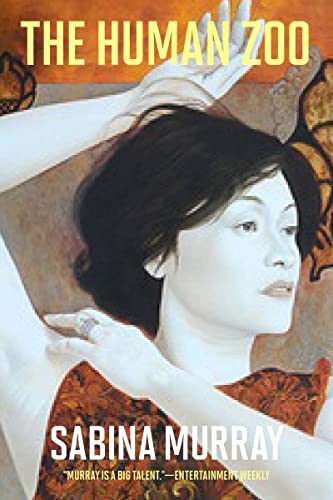

The Human Zoo

Sabina Murray’s novel The Human Zoo deftly interweaves a narrative of a woman’s search for identity, a historical, cultural, and political tale of Filipino society, and a tension-filled, action-packed story of life in contemporary Philippines under the regime of a dictator. The fusion of these three genres makes for an engaging, interesting, and informative novel.

Narrated by Filipino American, Cristina Klein, called Ting by her friends and family in the Philippines, The Human Zoo relates Cristina’s experiences in the Philippines as an escape from her impending divorce from her American husband in New York and to research a book she is working on about Timicheg, a Bontoc Filipino, who was brought to America in the early 20th century to be exhibited in a “human zoo.”

While in the Philippines, Cristina stays with her aged aunt in her aged aristocratic home, settles into upper-class life in Manila, attends numerous family gatherings, reconnects with her college boyfriend Chet, a wealthy businesman, and her best friend Inchoy, a gay socialist philosophy professor. Complicating matters is Laird, a distant cousin’s American fiancé, who mysteriously enters Cristina’s circle wanting to learn about Filipino society and politics. Ever present lurks President Gumboc, a stand-in for Duterte and his repressive regime.

Cristina, who narrates the novel, maintains a wry, distanced tone throughout, reflecting her position as both an insider and outsider. As an upper-class Filipino American journalist who has lived in the U.S. as well as the Philippines, Cristina observes carefully, judges, but remains detached. She explains, “During my years in the Philippines, I felt American, but back in the United States, I felt alien.” She claims about her Filipino family, on the one hand, “that although they are family, and I love them, I come from a different world.” But soon after concludes that she fled her husband in New York because “I had forgotten who I was and I wanted to remember.”

The narration is clear and straightforward, and often funny. As a writer, Cristina watches and comments on everyone. When describing her relatives and the social and cultural scenes in the Philippines, the narrator can be lovingly judgmental. She introduces a family ritual of going to a buffet: “Preparing for an outing to Dad’s World Buffet, as with a colonoscopy, entailed a certain amount of fasting.” Among her many observations of the endless traffic jams in Manila and the surrounding areas, Cristina dryly notes, “I looked down at Morato, where the traffic inched along, like pork in an alimentary canal.” But she is also critical of herself and Americans.

In addition to observing the foibles of her family and friends, the narrator also watches the political and economic situation in the Philippines. She gets loosely involved in a complex mess involving friends with varying positions toward the Gumboc regime. Like with Forrest Gump, things just seem to happen around her. Her ex-boyfriend’s wife accuses her: “You’re like a black hole. Everything is fine and then you walk past and everything is destroyed. And you can stand there and say you didn’t do anything, but you did.” Unlike her Filipino family and friends, she can leave easily.

The novel concludes with high drama involving murders, an escape, and political intrigue. While an engaging narrator, Crisitina is not entirely likeable. She judges and observes but does not commit or get involved meaningfully in anything. She spends months in the Philippines avoiding her husband and her research. She treats the Filipino subjects of her narrative as if they are part of the “human zoo” she is researching. But in her self-absorption and research she notices that she too is a spectacle. In her notes on her book The Human Zoo, she asks herself, “What is it to be other? If one is other, what is the thing this is not?”