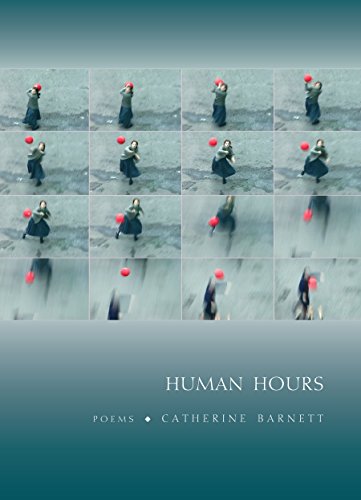

Human Hours: Poems

When reading the other reviews of Barnett’s Human Hours, one begins to wonder if the reviewers actually read it. Reviewers are so preoccupied with heaping praise upon the collection that they do not provide the constructive, supportive criticism that Barnett and her readership deserve in this diverse, and at times very experimental, body of work.

Human Hours is about self-discovery through relationships, social commentary, and philosophy. Rife with several references to literary and philosophical icons, such as Kafka, John Locke, Shakespeare, Samuel Beckett, and Kant, the collection risks alienating leisurely readers who seek sentimental and emotional fulfillment. Thus readers risk misinterpretation. Fortunately an appendix of notes is provided to aid understanding for those outside academia.

Barnett defies traditional poetics, dabbling with the experimental, especially with the “Accursed Questions” series throughout the book—there are four. Each prosaic poem presents a series of statements to frame the poet’s current mindset (hour of being human).

Here are statements from “Accursed Questions, i”: “A doctor suggested I spend four minutes a day asking questions about whatever matters most to me.” “Lately I’ve been walking around talking to myself, who is full of swearing and disbelief.”

The “Accursed Questions” exemplify the collection—talking to oneself, with polarizing senses of disbelief and narcissism.

Poetry must be accessible, thus the strongest poems are those with clear images and metaphors.

“The Humanities” is particularly strong, a poem which rejects the study of physics, favoring childhood imagination. The study of pendulums is contrasted with swinging in a tree “smiling, white, / safe and dumb.” Swinging in the trees and reading lines from a play create a metaphor for innocence and joy, joy which is not experienced in the sciences.

Another enjoyable poem is “Still Life”. The poet experiences the concept of beauty by viewing her throat during a medical exam: She uses her body as the poem’s landscape. Observe: “Seen from the inside, lit from within / like the intimacies of L’Origine du monde, / a painting I love because it makes // beautiful what I’ve mostly kept hidden / in shame. Cunt, some of you have called it, / or God, pulsing there in the small gilt frame.”

Barnett’s poetry draws its strength from images. Her images are clear and stark. Proper nouns and accurate references are used to prove meaning. Barnett also takes risks by challenging reader knowledge of literature and philosophy. Human Hours leaves us thinking, thinking within all hours of life.