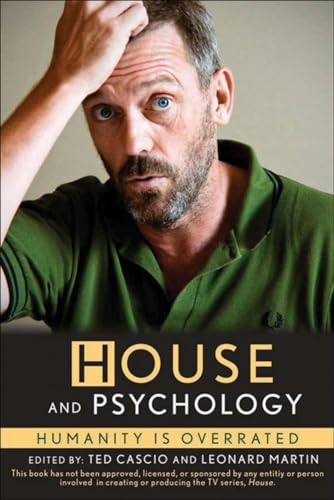

House and Psychology: Humanity Is Overrated

“This book should be read by all “House” fans. . . . All students of psychology . . . Basic issues of personal behavior are covered in a clear, understandable fashion. People who just enjoy a good read will find this an enjoyable book—sometimes annoying, sometimes funny—but never dull. Kinda like House himself.”

Over the years, television has brought the American public a number of fictional TV physicians (as well as the real-life Dr. Oz and the team appearing on “The Doctors”). Perhaps the quintessential family physician was Marcus Welby, M.D., starring Robert Young and airing from 1969–1976. Dr. Welby was kind, caring, and astute.

Among other TV physicians were Doogie Howser (the teen wonder), Dr. Kildare, “Bones” from “Star Trek,” Cliff Huxtable (aka Bill Cosby), and a number of others. But nowhere do we find one with all the weird quirks and failings of Dr. Greg House, the start of the current popular TV series, “House.”

This fictional individual is analyzed and characterized in House and Psychology by a group of (mainly Ph.D.) psychologists from a variety of subfields within the discipline. Each contributor watched the series on DVD in preparation for their assignment. The outcome of all this viewing is an interesting and challenging collection of chapters exploring different aspects of the personality of this eccentric and unorthodox physician.

Through these pages, we see a man who has extreme difficulty in forming relationships. One of the authors raises an interesting question: House grew up in a military household, which meant frequent moves and stays that may have only lasted a year or two before going on to the next duty station. The issue of whether this environment affected House’s relationships is briefly raised at the end of the book, but never explored. Anecdotal evidence suggests that frequent moving and an often unstable environment can impair social development and the ability to form strong relationships in later life.

The contributors explore different aspects of the House psyche. Does House really want to help people or is he more interested in the challenge of a clinical mystery to be solved? How rebellious is he really? What are his drug dependency issues all about?

Is House a hero or a villain?

There is a complex interplay of behaviors in this man that are often contradictory and puzzling. No individual writer appears to get a good handle on House.

The real value of the book is, in fact, not whatever light it may shed on House. After all, TV characters are allowed to change from week to week to build suspense, create interesting conflict, and keep viewers watching the show.

No, the book serves a much more useful purpose in providing insights into a variety of human relationships. One of the editors points out in the introduction “. . . this book is chock-full of scientifically valid, research-based psychological knowledge; so much so, that is would serve quite well as a supplemental text for psychology instructors at high schools and universities.”

Each chapter concludes with a series of references from the current psychology literature that provides further information for those who wish to learn more.

In all books written by teams, there is some inevitable unevenness in style and approach. Perhaps the least satisfying chapter deals with House’s drug addiction. The author tries to straddle a line between the psychological issues and the neuroscience of addiction and leaves the issue somewhat unresolved. But that lack of resolution also helps to demonstrate the ambiguities that exist in our present understanding of drug addiction.

None of the writers is a physician and presumably none have worked in a hospital environment, so they do not raise any real alarms about the conduct of this physician.

This reviewer is intimately acquainted with this setting, having directed a hospital chemistry lab for 13 years and serving on a quality assurance committee for a hospital consortium for over a decade. Knowing the standards that physicians must maintain, it is very surprising that Dr. House is even employed, much less given the leadership of a clinical team. His lack of professionalism and his on-going refusal to follow policies and procedures make him a danger to himself and others. In the real world, he would not be allowed to practice medicine.

This book should be read by all “House” fans. Readers will gain some very useful insights into the mind of the eccentric and unpredictable doctor who is the pivotal character. All students of psychology should also read this book. Basic issues of personal behavior are covered in a clear, understandable fashion. People who just enjoy a good read will find this an enjoyable book—sometimes annoying, sometimes funny—but never dull. Kinda like House himself.