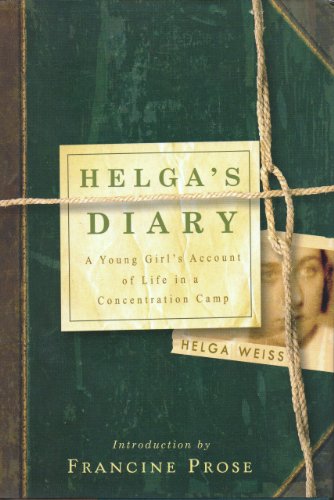

Helga's Diary: A Young Girl's Account of Life in a Concentration Camp

“. . . a window to the massive Nazi plan to rid Europe of every Jewish man, woman and child. Of 15,000 children deported to Terezin and later to Auschwitz only about 100 of them will survive.”

Helga Weiss enjoys a happy, well-nurtured childhood in Prague loved by family and many close friends; the decade of the 1930s is closing with promise and excitement.

Then in 1939 Nazi Germany invades Czechoslovakia and everything in Helga’s world suddenly changes. Jewish children are forbidden from attending public schools. Their parents lose jobs, bank accounts, and valuable property. They are forced from their homes into a decrepit ghetto, where many families must live together in squalor.

As 1939 melts into 1940 rumors about prison camps “in the East” become rampant. Soon word arrives that some of those camps are designed to mete out industrial death to Jews on a massive scale. Suddenly, their horrid ghetto seems like a good place to live.

By this time, Helga has begun writing a diary. She feels that it might one day be important to capture the people, places, and events along her journey into a living hell.

In 1941, Helga and her parents are transported to the concentration camp Theresienstadt (also called “Terezin”).

Helga’s Diary provides a daily account of life in Terezin, Auschwitz, and other Nazi concentration camps and death camps. In the book the author describes abject misery from slow starvation, rampant sickness, forced labor, the brutality of camp guards, and the deaths of family and friends. The diary is a window to the massive Nazi plan to rid Europe of every Jewish man, woman and child. Of 15,000 children deported to Terezin and later to Auschwitz only about 100 of them will survive.

Helga is 15 when she and her parents arrive at Terezin. Her writing largely reflects the unbound innocence, resiliency and enthusiasm of a young girl. The brutality that she experiences begins to temper her future posts. Instead of attending her Prague school and working on art projects or mathematics, Helga is suddenly forced into hard labor, welding airplane parts in German factories.

Religious holidays and birthdays come and go surrounded by only cruelty, pain, and suffering. Despite the conditions, we still sense Helga’s unbridled zest and enthusiasm for life, her enduring love for family, and her unbound anticipation for a rewarding future.

Helga, like almost everyone else in her barracks suffers from typhus and starvation. There is almost no medical care for the prisoners. Helga slips into a life-threatening illness for which there is no available treatment. It seems that Nazis only value Jews who are sufficiently healthy to work. While typhus rages within the camp, Helga falls into a limbo between death and life.

The months and years pass by, while Helga manages to remain close to her mother, separated by buildings, but in the same concentration camp. However, with men and women divided, Helga is separated from her dear father. The thought of losing him weighs heavily upon Helga’s mind.

After being deported from Terezin, Helga’s father disappears, as did so many millions of other victims of Nazi brutality. To be sent to a Nazi gas chamber requires only the appearance of advanced age, infirmity, disease or rebelliousness. Even something as simple as wearing glasses becomes a ticket to the gas chamber. Only the strong survive, because they can perform the Nazis’ rigorous forced-labor.

Helga and her mother barely endure Auschwitz, despite rampant illness and the Nazis desperate need to gas and burn hundreds of thousands of Jews as rapidly as possible. By 1944, it becomes apparent that Germany is losing the war.

Surrounded by the allied armed forces, it’s only a matter of time until the concentration camps are liberated. The Nazis decide to cover up their massive genocide. Jews are forced to gas and burn people as quickly as possible. In Auschwitz, the crematoria chimneys belch acrid fire and smoke high into the air, like some horrid candle pushing the ashes of Jews into infinity. Helga and her mother are soon to be dispatched similarly.

Before the Nazi SS can murder everyone at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Russian troops arrive upon their doorstep. Unable to complete their mission, the SS order prisoners on a massive death march, including Helga and her mother. Years of starvation and sickness have taken a vast toll. Helga and her mother are near death. It is uncertain whether they will die along the long march or after they arrive at a new Nazi death camp in Germany or Austria.

Helga’s Diary is extremely well written. Helga had little need to embellish her diary after the war because it was so accurate, evocative, and informative. Fascinatingly, we see the development of her writing skills as she ages. While Helga’s initial diary posts focus upon simple facts and places, as one might expect from a 15 year old, her entries years later reflect the work of a woman whose writing skills have developed into excellent prose. Her detailed and eloquent description of the final death march rivals the writing of any skilled adult.

Helga’s uncle, also imprisoned at Terezin, takes possession of the diary after Helga and her parents are deported to Auschwitz. He works in the Terezin records department. Before Helga is sent to Auschwitz, she tells her uncle about the diary. He hides the diary inside of a brick wall until the war ends. Miraculously, he is then able to find it and return it to her.

If this reviewer has any disappointment with Helga’s Diary, it is the absent culture of Theresienstadt. Europe’s most well-known Jewish artists, physicians, professors, inventors, politicians and musicians are sent to Theresienstadt. Nazi leadership understands that the world might one day question where these prominent people had gone and how they are being treated. Nazis created Theresienstadt as a “show camp.”

In the end, almost all of those prominent Jews are murdered. The ruse fails. Yet this reader had hoped to learn more about the Theresienstadt Jewish schools, orchestras, bands, concerts, lectures, and all manner of the arts established by Jews within Theresienstadt to make their children less afraid. Perhaps Helga was not part of this social and educational aspect of Theresienstadt.

Nazis manufactured films and documentaries inside the camp meant to show the world how well they treat their famous Jews. To this extent, a ruse was accomplished with the Red Cross, in which the healthiest young Jews are forced to pose as happy, fun-loving people, thanks to Nazi generosity. Embarrassingly, The Red Cross falls for this subterfuge, hook line and sinker.

Helga’s Diary is significantly enhanced by illustrations, drawings, maps, diagrams, and pictures liberally sprinkled throughout the well-written text. Visual learners are bound to enjoy this added sensory flavor of Helga’s account. This fine book is topped off with a very interesting interview of the author at the conclusion.

After the war, Helga enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague, where she later became an artist. To this day, she lives in the house in Prague where she was born.