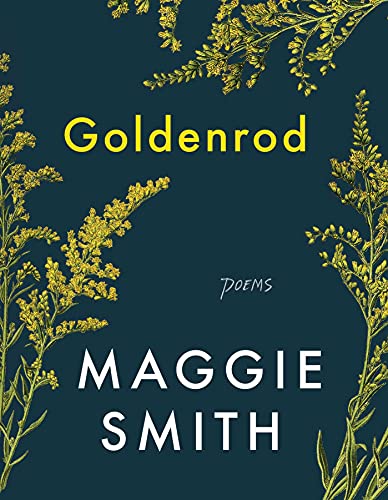

Goldenrod: Poems

Maggie Smith’s poetry collection Goldenrod emerges from a place of stillness. It records the small details that have come to dominate so many people’s lives since the beginning of the pandemic: the flowers, the birds, the news-broadcast-borne atrocities of political life. The domestic interior is carefully studied, almost safe, breathtakingly beautiful. It holds, a perfect view, until the terror beyond the door seeps through the cracks, breaking apart the moment of serenity.

That tension is present from the first poem, titled “This Sort of Thing Happens All the Time.” The “sort of thing” in question is not violence but its ignored proximity. “One night . . . on a dark street in the suburbs, . . . through blue windows you watch / the evening news. The anchor’s mouth / is moving.” If we release the still beauty of the world even for a moment, horror will flow in. But if we remain tense, we can focus on “Crickets and that broken-sounding bird. / Then one dark barking. Then two.”

This juxtaposition, which pervades the collection, reveals an essential truth of American middle-class life: the security of domestic life was created by violence (at borders, in wars, by police against children), and now violence, not security, is the cultural dominant. State violence enters the house in “Airplanes.” The title whispers of global terrorism, but the poem itself stares (flinchingly, too horrified to be unflinching) at racial terrorism: “My son is safe in bed, the opposite / of gutshot. . . . / That’s me, there, the shadow / that shielded his eyes each time / the year shot another / mother’s son in the street. No, / not the year, never the year.” The white mother, protector of a particular version of innocence, sees what her suburban existence tries to exclude. No such vision can be excluded or ignored.

Against this awareness of racist violence, the book’s quieter reflections on the end of a marriage mark another layer of realism. “At the End of Our Marriage, In the Backyard” names self-righteous inertia: “We do nothing and call it something—as if / this wilding were intentional. If there is honey, / I tell myself, we are to thank.” The wry examination of a garden neglected becomes a powerful metaphor for white liberalism: inaction adorns itself with an aura of good intentions, then takes credit for the labour of others.

Many poets explore the domestic interior. It’s been fertile territory for the poetic (white) feminine for generations. Maggie Smith, without naming that happy fertility, explodes it. The fertility of her poems are wild-growing plants and children, but the interior is inside out: the quiet, safe world unable to sustain itself for even one more page. Smith digs into the “idyll” of suburban childhood now and a generation ago, revealing the falseness of that beauty: “America, as a girl I rode my bike / around the cul-de-sacs: Lexington, / Bunker Hill, Valley Forge.”

In the book’s third part, spring becomes a season of looking beyond. Smith’s persona speaks to a child, and clearly to herself: “You must think this house is the world.” Yet the rush to openness and real confrontation crashes into pandemic inertia. A daughter “cried at bedtime / Of loneliness”; a mother tells “her the steep peak makes loneliness / our work, makes an honorable task of it.” It’s true, but also troubling: how can stopping, turning inward be the answer? Assurances that this is temporary feel hollow. Everything repeats, cycles, returns to an earlier state. Singing is no way forward, and “We must be coming / to the chorus now.”