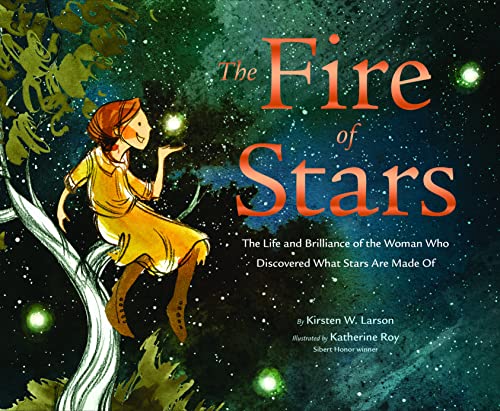

The Fire of Stars: The Life and Brilliance of the Woman Who Discovered What Stars Are Made Of

“beautiful . . . contrasting images of stars and outer space.”

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin is definitely a scientist worth knowing about, but this picture book manages to only skim over her achievements. The illustrator has done a beautiful job of contrasting images of stars and outer space with Cecilia’s daily life, but that’s not enough to give a sense of what Cecilia’s discovery actually meant at the time. In fact, the writer never gives a date or provides a historical context. For any sense of that, one needs to go to the backmatter, which does have a timeline, a bibliography, and a brief outline of Cecilia’s work.

The writer begins predictably enough with Cecilia’s childhood, but her first flickerings of scientific exploration is introduced as “making friends with trees and flowers.” Her observations, the beginning of her interest in biology, is described:

“Cecilia realizes all by herself why an orchid has a petal like a bee’s belly

To trick the bees, of course!

They buzz over to say hello to their pretend friend, then fly off with pollen-stuffed pockets. . .

Cecilia buzzes, too, too—her body humming with that lightning bolt of discovery.

She wants to feel that way forever.”

In fact, when Cecilia described this “bolt” of discovery in her memor, it was about recognizing a species, not identifying the evolutionary reason for the shape of an orchid petal. This is only one of several misrepresentations of Cecilia’s education and journey to becoming an astrophysicist. The most important lapse is in the description of the discovery of the title, what stars are made of:

“Through her careful calculations and hours of observation, the rainbows of starlight share their secrets with Cecilia.”

What are these “rainbows”? The author means spectra, the lines on photograph plates archived in the Harvard observatory, but calling them “rainbows” won’t mean anything to the reader. The text continues:

“They show that stars are mostly hydrogen and helium, not like the rocks and minerals of our spinning planet.”

How was this revolutionary? What did her fellow astrophysicists think of this? Why did it matter? None of these questions are addressed. Instead, the writer moves smoothly into how this discovery could launch other questions, such as how stars form. These other questions, however, aren’t the ones Cecilia follows up, important though they may be. The book tries to be inspiring, and perhaps at that level it works, but as an historical introduction to a pioneering astrophysicist, it remains heavily earthbound. To be fair, this would be a difficult subject for a picture book, but there is now a genre of older picture book biographies with more complicated subjects and information. This title, sadly, doesn’t fit into that format. Nor does it satisfy as a younger picture book, incomplete and insufficient as it is.

The bibliography suggests that Larson has done extensive research, and she once worked with scientists at NASA. She clearly has the background to tell this story. What she lacks is an understanding of the picture book biography format, the need for narrative drive and character development. As it is, she’s done a book that’s beautiful to look at, but it remains one that sketches a sense of a story without telling the story itself.