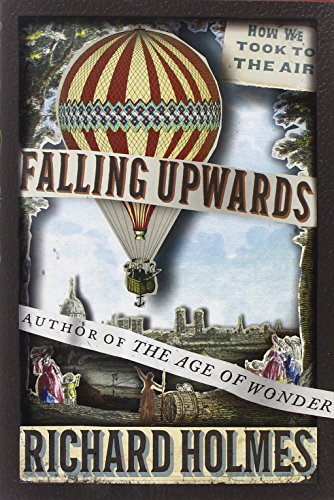

Falling Upwards: How We Took to the Air

“. . . reads as easily as a novel, loaded with derring-do and emotion . . .”

Ballooning has long been recognized as the starting point of aviation history, later becoming a sideline as powered flight took over the world.

But balloons have their own story-within-a-story that Mr. Holmes brings alive in his new book.

Although it’s a chronological history of “aerostation” (the art and science of lighter-than-air flight), his intention is to expand and deepen that history. Thus the book “. . . is not a conventional history of ballooning. In a sense, it is not really about balloons at all. It is about what balloons gave rise to. It is about the spirit of discovery itself, the extraordinary human drama it produces; and to this there is no end. It also explores how a single, counter-intuitive scientific discovery—that hydrogen can be weighed against atmospheric air—can have such huge social and imaginative impact. In this, it is about the meeting of chemistry, physics, engineering and the imagination.”

This paragraph appears at the end of the book instead of the beginning, so that readers see for themselves what Mr. Holmes is talking about before having it summarized for them. The story begins on a personal note that draws the reader in then takes off in an interesting, almost balloon-like narrative, viewing history from above in a broad perspective.

At the same time, it zooms in on the special people who were captured by the dream of flying and dedicated their lives to pursuing it. These aeronauts developed balloon technology and extended its flight range through the sheer vigor of their obsession.

The book progresses through their tales, starting with a sketch of balloons in prehistory then detailing recorded history from the 1700s onward. It features European and American balloonist-dreamers and their enterprises and journeys.

None are household names in the U.S., though students of aeronautical history probably are familiar with them. Many left behind written and photographic records of their experiences, or were reported about by others. Balloons were a Really Big Thing until airplanes came along.

Ballooning caught the imagination of not only scientists, explorers, and inventors, but also artists and writers. Here literary household names abound: Dickens, Verne, Wells, Hugo, Shelley, Poe.

Important politicians and military leaders got swept up in the excitement, too, seeing balloons as critical tools in warfare. They were used to advantage in the American Revolutionary and Civil wars—but the most fascinating story comes from Paris.

In 1870–71, the city was besieged for months by the Prussians. In an amazing and inspiring effort, the balloon zealots of the time organized “the first successful civilian airlift in history. . . . If it did not win a war, it saved the morale and even the soul of a nation. It was the finest hour of the free-flight gas balloon.”

This story alone makes the book worth reading.

But many other stories are just as engaging. There’s petite Sophia Blanchard, a free-style balloonist, who ultimately became the Aéronaute des Fêtes Officielles for Napolean in the early 1800s. She sailed solo around Europe, including over the Alps, performing acrobatics and managing fireworks shows in spectacular costumes. Then there’s James Glaisher, who explored high altitude without oxygen; Felix Nadar, who brought ballooning to both public and political importance; and Salomon Andrée, who attempted to reach the North Pole.

Some of their stunts and expeditions ended badly, but an impressive percentage came to happy conclusion. Mr. Holmes, in keeping with his broad perspective, recounts key disasters as well as triumphs. He also covers meaningful efforts that, literally, did not get off the ground.

In the main, he keeps the book focused on how these intrepid individuals contributed to meteorology, reconnaissance and mapping, engineering, and military strategy. Their combined energies changed the course of the world.

Fittingly, the book is presented in a package of unusual quality in today’s lean publishing economy. The jacket is handsome, embossed, and sturdy, and the cleanly designed interior—typo free—contains maps and illustrations along with three insets of color plates.

The backmatter provides well-organized notes for both the text and illustrations, a thorough bibliography, and an index. The narrative stays on track with asides marked with both numerical links to the explanatory back matter and footnotes for which the asterisk is replaced by a cute little balloon graphic. The whole is polished and professional, worthy of home and municipal libraries.

It’s hard to compose facts and figures into a volume that reads as easily as a novel, loaded with derring-do and emotion. Mr. Holmes has succeeded at that challenge, profiling an important but underexamined aspect of human history that is uplifting in all its forms.