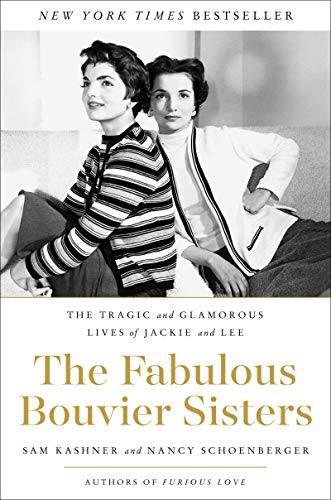

The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters: The Tragic and Glamorous Lives of Jackie and Lee

Was it only seven years ago when self-referenced “veteran entertainment reporter” Sam Kashner teamed with biographer Nancy Schoenberger to produce that rock-’em, sock-’em tome Furious Love: Elizabeth Taylor, Richard Burton and the Marriage of the Century? Indeed.

And did it ever live up to its title, a mix of lust, love, alcohol and diamonds. Chasen’s chili, airlifted from Hollywood to European movie sets for the pleasure of the most famous woman in the world and some Welsh guy she met while whiling away an afternoon in the shadow of some pyramids. Big movies, even if for every Virginia Woolf there was a Boom! And career highs and career lows and Private Lives on Broadway, during which the actors onstage were as crocked as the characters they were playing. And fury, always fury, to say nothing of passion and anger and jealousy and sighs and screams and ice cold champagne, and gigantic diamonds, and marriage and divorce and remarriage and divorce and then death, which sort of put an end to it.

Furious Love was a great book, salacious, but with footnotes.

With the success that Liz and Dick brought them all, it must have seemed a great idea to Kashner and Schoenberger, to say nothing of their publishers, editors and agents, for the duo to find some other duo to write about, ASAP.

But who?

It had to be a pair who were equally famous, if such a thing were possible. Another pair who bestrode the two decades, the ’60s and the ’70s, when there were still only three networks and cultural giants strode the earth. When fame was more newsprint than Internet.

There was only one twosome to consider, really. Only one pair whose faces (well, one face really—the other face fell most often a little out of focus behind the first) whose images were more photographed more (and more lovingly) than Elizabeth Taylor and her then-husband.

Whoever thought of the identities of the subjects for the next project must have turned to the other, over the table at Nobu or some-such, with their eyes popping out of their head. And as they clasped hands over the sushi platter, their giggles were heard echoing throughout the land.

Seven years later, we have The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters: The Tragic and Glamorous Lives of Jackie and Lee, which, by its very title promises us so very much: Greek islands, private yachts, pillbox hats, questionable royal titles, trysts and affairs and flirtations by the dozen, political intrigue, sudden deaths, interior design, Truman Capote and Gore Vidal, together and separately.

The question is, though, do the Bouvier Sisters deliver?

The question is answered with a sigh, really.

A sigh that signals both a sense of disappointment and of satiation.

The reader wants very much to love The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters. Enters into the text with his mind made up to enjoy every minute of the thing, right from the decision to publish in the introductory pages the complete text of the poem “Ithaka” by one of Jackie’s favorite poets, C. P. Cavafy, from which I lift this:

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you’re destined for:

But don’t hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

So you’re old by the time you reach the island,

Wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way,

Not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

The reader’s mojo continues to rev, as the book begins with this:

“Jacqueline Kennedy, the greatly admired First Lady, was diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at the age of sixty-four. The illness spread rapidly through her body, and Jackie opted to die at home, in her spacious apartment at 1040 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. Lee Radziwill rushed to Jackie’s side when she learned of her sister’s illness. For a brief time, their long, complicated relationship seemed to melt away and they were just sisters, as close as they had been in their youth.”

I mean, who could ask for more?

Then the reader is further tantalized as the authors pull back from Jackie’s deathbed to the sisters’ births, with this:

“The beautiful Bouvier girls—Jacqueline Lee and Caroline Lee” (note that their twin middle names do not reference a peculiar affection on their mother’s part for that name “Lee,” but instead are examples of high society’s tendency to middle name their children with their mother’s maiden name)—“were bred to dazzle. Jackie was born on July 28, 1929, at Southampton Hospital on Long Island. Lee arrived there three and a half years later on March 3, 1933. In contrast to her dark-haired, athletic sister, she was light-haired, chubby, mischievous and loved to be the center of attention.”

The subtext here is that, since the book is about sisters born to dazzle, the reader should prepare to be dazzled—right?

Unfortunately, a few pages later, soon after Gore Vidal, leading American author, raconteur, and vindictive gossip (as well as kind-of stepbrother-once-removed to the girls by way of their mothers being married, at different times, to the same magnate), reports that Jackie, while lounging on a chaise lounge one sunny afternoon in Hyannis Port, once turned to him and said, “I’ve kept a book. With names,” the crackling expectation begins to dissipate.

Mostly because of the names that don’t get named.

Where the hell, for instance, is Marilyn Monroe?

She merits only a couple of mentions, both of which center of how strange it was that she and Jackie shared the same whispery little girl voice. Which is was, come to think of it. But given that Jackie chose not to be in the arena when Marilyn sang her breathy Happy Birthday to Jack, a paragraph or two is called for, especially given that the subtitle does promise both tragedy and glamor and Marilyn was so very good at both.

And what of the rumored relationship between Jackie and Bobby Kennedy, Jack’s younger brother? That is dealt with in a single sentence, which hints that the affair likely did happen, although, if it indeed did, shouldn’t the topic have been explored a bit more broadly?

It’s not like the book does not breathlessly report on the girls’ various romances. There is, for instance, and endless recounting of Lee Radziwill’s liaison with photographer Peter Beard. And the story of her long, sad, marriage to Stas Radziwill, a relationship of the kind that just slowly fizzles, like the helium draining out of a balloon that drifts into the corner and ultimately bobs down to the floor. Stas did share two beloved children with her (one of whom, their son Anthony, would marry Carole Radizwill from The Real Housewives of New York City, who gets a whole lot more ink in these pages than Marilyn did) and the titles Prince and Princess Radizwill, although the veracity of the title remains in question to this day.

Only two of Lee’s romances catch fire with the reader.

The first was with Rudolf Nureyev, for whom Princess Radizwill had to pretty much fight off Princess Margaret, as neither seemed to notice that Nureyev was a rather dedicated homosexual.

The authors tell us that “Lee found in Rudolf Nureyev the apotheosis of artistry and a kind of peacock beauty that mirrored her own lean, high-cheekboned face; in photographs, they could have been twin descendants of the Tartars.” And concludes that Rudy and Lee ultimately became sort of a jet set Will and Grace and let it go at that.

The big surprise among Lee’s many suitors—most of whom waltzed into her life during her long marriage to Stas—was that it was Lee who first bedded Aristotle Onassis, and who first set her mind to marry him:

“Onassis completely thrilled Lee, and not just because of his immense wealth and power. He was warm with an earthy charm and a strong sexual presence.” (Lee later confided that she liked his “primitive vitality” and she described his “sexual prowess, his Oriental tastes in that area.”).

Needless to say, the sections of the book that recount Lee’s relationship with Onassis, Jackie’s marriage to Onassis, and the transition from Lee to Jackie are among the book’s best.

As are the sections in which we meet the Edies, Big and Little, who were the subjects of the documentary Grey Gardens, as well as the Halloween costumes of many a gay couple. We learn that the film began its life as Lee Radizwill production, starring Lee Radizwill, who was in front of the camera for many hours of film, notably when she was seen giving the Gardens a clean coat of paint after she discovered the disarray into which it had fallen.

But then the Maysles Brothers got ahold of Little Edie being staunch, which left poor Lee on the edit room floor.

There’s also the wonderful bit in which Jackie hires Sister Parish, the famed decorator, to help her spruce up the White House.

Because it was a government project, it was to be strictly budgeted, with the budget set at $50,000 (which would translate roughly into $350,000 today), which had been privately raised.

As the authors note:

“Jackie ended up spending the entire budget in the first two weeks on the family’s private quarters on the second floor, adding a kitchen and dining room.”

And so other funds had to quietly be raised, and rich collectors had to be convinced to share their precious antique furniture and superb artwork with the White House, at least long enough for Jackie to show it to the nation on her televised tour of the estate.

And there’s the too-brief moment set in the Amber Palace, when Jackie and Lee decide to teach the Maharaja of Jaipur how to do the Twist.

But perhaps surprisingly, given the book’s dedication to good gossip, the single best section of The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters is that which tells of the assassination of Jack Kennedy, and of Jackie’s response. The images of Jack telling Jackie Kennedy to remove her oversized sunglasses before getting into the convertible in Dallas, because, “You’re the one they’ve come to see,” or of her in her blood-stained pink suit, only hours later, refusing to change clothes and saying, “Let them see what they’ve done,” or, days later, back in Washington, walking behind her husband’s casket, “leading a delegation from ninety-two nations led by Charles de Gaulle,” leap off the page and linger in the mind’s eye.

If only the book could sustain itself. Or paint all moments as vividly as these. If only the authors were not so dedicated to support the ego of the text’s only survivor, Lee Radizwill, who outlived them all. If only the section in which Truman Capote convinced the princess that she ought to remake the noir classic Laura for television, with George Saunders filling in behind the shotgun for Clifton Webb in the film classic, were more honest and less kind.

The authors pitch underhand here as they do in so many other places. Anyone who has seen even clips of the made-for-TV movie know how howlingly bad it was, and what a mistake it was for listening to anything that Capote suggested. But in these pages the whole mess gets the Huckabee treatment and it is suggested to the reader that it wasn’t really all that bad.

So our beloved president and Jackie’s beloved husband dies, and the nation mourns and she mourns, and, for a time, it seems as if the mourning will never end.

But, “three years after Kennedy’s death, Jackie had traded in her tasteful A-line dresses and demure necklines for miniskirts.”

And she marries Ari. And Lee has to read about it in the newspapers. And she calls Truman Capote and cries and cries.

There are divorces, and, in Onassis’ case, deaths right after divorce, and other deaths soon after, and Jackie gets richer and richer and Lee gets poorer and poorer, having driven poor Stas, both before the divorce and after, into having to sell pretty much everything there was to sell to keep her in townhouses and the latest fashions.

And Jackie meets Warhol and his ilk. And Warhol for years after dines out on his Jackie anecdote—that the first words to him from Jackie were in the form of a question: “So tell me, Andy, what’s Liz Taylor really like?”

As the anecdote was told, “Here’s the only person in the world who was more famous than Elizabeth Taylor and she wanted to know what Elizabeth Taylor was like . . . And what’s more, it was asked in the voice of Marilyn Monroe. If Marilyn had gone to Foxcroft and Vassar, that is.”

And, on and on, and before you know it, we are back to Jackie’s deathbed. And the reading of the will (spoiler: nothing for Lee), and the smart readers stop reading right there, as the best parts of the story have all been told.

From here, more deaths, Lee downsizes, gets old. Gets lonely.

And we get to the last chapter, in which we get slapped in the face with a question that does not need asking: “How does Lee live now?”

Suffice to say that she is holding her own.

Perhaps the sad truth is that, of the two, it was Jackie that we wanted to know, or, at the very least, know about. And perhaps Princess Lee was all too aware of this fact, which perhaps was the reason for her ultimate betrayal of her sister, of Camelot, of the whole Bouvier nonsense in a conversation with author/critic Christopher Hitchens, who was himself on his deathbed at the time.

And, finally, perhaps the best assessment of the sisters’ relationship is given to us early on, by Gore Vidal’s mother, Nina, who always rather resented the fact that the Bouvier mother had married her ex-husband. As our authors recount, she “described Jackie and Lee’s relationship as S & M, with Jackie doing the S and Lee doing the M.”

Get that into your head early on and the whole rest of the book just falls right into place.