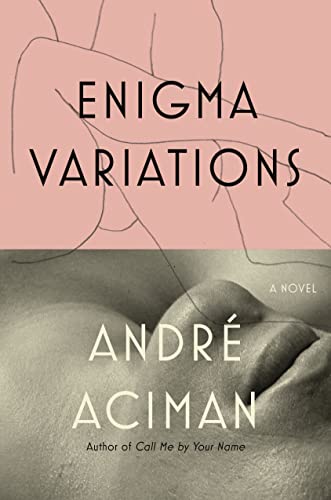

Enigma Variations

Enigma Variations, the new novel by Andre Aciman, who previously presented us with that peach of a tale, Call Me By Your Name, has been packaged strangely. What with the pink and gray cover—with the title and a kind of doodle of naked legs intertwined in the pink box at the top of the page, and a close-up of lips in the gray—and a good amount of hyperbolic nonsense printed on the flap:

“In Enigma Variations, Aciman maps the most inscrutable corners of passion, proving to be an unsparing reader of the human psyche and a master stylist. With language at once lyrical, bare-knuckled, and unabashedly candid, he cast a sensuous, shimmering light over each facet of desire to probe how we ache, want, and waver, and ultimately how we sometimes falter and let go of those who may want to offer only what we crave from them.”

Someone, some publicist, or perhaps the author himself (it happens), must have sighed the sigh of completion, of satisfaction, after having knit together these particular words in order to sell the book.

And yet they, in doing so, ignored the risk that some potential reader, reading this word salad (“inscrutable corners of passion,” “sensuous, shimmering light?”) might choose instead to reread Great Expectations.

Here is what you need to know about Enigma: It is a worthy successor to Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name. It is a thing of beauty, with sentences that suck the breathe out of the reader like a malicious feline out of a sleeping baby.

Like this, from “Manfred:”

“You know nothing about me. You see me. But you don’t see me. Everyone else sees me. And yet no one has the foggiest notion of the gathering storm within me. It’s my secret private little hell. I live with it, I sleep with it. I love that no one knows. I wish you knew. Sometimes I fear you do.”

This illustrates the novelist’s trick: taking simple words, everyday words, and transforming them into something new, into something that seems stolen from another language, something that translates that which had heretofore been untranslatable. (Even if the grammar does not live up to the language and that errant comma stands where the semi-colon belongs.)

Enigma Variations is fiction told in layers. It comes at you in chunks, like one of those books of intertwined short stories about cranky folks up in Maine. They have titles that separate them, “First Love,” Spring Fever,” “Manfred,” Star Love,” and “Abingdon Square.”

And like collections of short stories, they achieve varying degrees of success.

The first layer, “First Love,” sets the stage with our protagonist getting kind of Brideshead-y and going back to the Italian island of his youth (there is, because of this, entirely too many mentions of the ferry—so many that the reader contemplates a drinking game) to take a look at the embers of the family home that mysteriously burned to the ground. Memories unfurl, coffee is drunk in beautiful cafes, and pastries are eaten.

“I’ve come back for him,” the story begins.

It continues:

“These are the words I wrote down in my notebook when I finally spotted San Giustiniano from the deck of the ferryboat. Just for him. Not for our house, or the island, or my father, or for the view of the mainland when I used to sit alone in the abandoned Norman chapel in the last weeks of our last summer here, wondering why I was the unhappiest person on earth.”

The reader, if he has any sense at all, is at that point ensnared by a thing that promises never to let him go. Things are, after all, sun-drenched, right there on that ferryboat. Memories of a Mediterranean sort being the hardest to dispose of must, I guess, be put into words.

And then, of course, there is the mystery of just who him is, the guy who seems more important than the burned relic of the home.

About him, there’s this:

“He touched the exaggeratedly rounded corners of the desk, let his hand rest there, as on the rump of a docile pony. Then he placed a hand on my back as I pretended to peer into the cavity where my grandfather’s box had lain hidden for so long. To prevent him from changing the subject or from removing his hand if my mother was to speak, I kept looking in and stringing one question after the next about the wood, the design, the products he used to remove the layers of grime to bring back to life the shabby object that had always languished in a corner of our house.”

Aciman is a sensualist. Perhaps the foremost sensualist of our cold and lonely age. This, melded to the poetic force of his language (the reference to that “docile pony” kills) makes him one of the best novelists working.

“First Love” succeeds wonderfully well, opening the door to the whole of the novel and to the protagonist’s heart.

Or so the reader thinks. But nothing can be so simple in a novel whose title contains only two such freighted words as “enigma” and “variations.” (We’ll get to Elgar in a moment.)

To revisit Brideshead again for a moment, think about Charles Rider and his first love for Sebastian Flyt. And his second for Flyt’s sister, Julia.

There are any number of Sebastians and Julias here, as our protagonist, Paul, seems equally fluid in terms of sex and love, both. Making it hard for the reader, at any given moment in the text, and most certainly after having finished reading it, to pin down just what or who it is that Paul wants.

Which plays well with Aciman’s wonderful title, that nod to the music of Elgar, who, after his variations were performed, wrote:

“The enigma I will not explain—its ‘dark saying’ must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connections between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole set another and larger theme ‘goes’ but is not played—so the principal Theme never appears . . ."

Which is pretty much what the author of the new book by the same name could say as well.

In other words, if love, desire, gender identity and/or the love object itself, all squished together comprise the enigma, the variations are to be found in the stories themselves, and in the Sebastians and the Julias. In the way in which they are all joined together by desire and being desired, and yet are otherwise quite unique, and bundled together by the timeline of one man’s life. Some are his ghosts, left behind, perhaps grasping out at his heel as he walks away. Others are, like cars ignoring stoplights, accidents waiting to happen.

The issue that the reader has with Aciman’s work is that not all of the layers contained within are of equal value. Along with the first, the third, “Manfred,” is of stellar quality. Indeed, that third section of the work is among the finest things that the reader has plowed through in a good long time.

The achievement of the work is only enhanced in that Aciman tells it in second person. He writes it as if it were a long epistle to the latest love object, and then spins the story so well that it transcends the strict structure of the voice and becomes a merciless thing, a thing that sees everything, admits everything and demands everything, both of poor Manfred and of the reader.

It begins:

“I know nothing about you. I don’t know your name, where you live, what you do. But I see you naked every morning. I see your cock, your balls, your ass, everything. I know how you brush your teeth.”

And, having read it, having experienced the writing and the wanting spelled out in that writing, the reader sighs in completion and in satisfaction.

And perhaps, he thinks later, having read the whole of the work, it would have been better to stop there and not stayed on to see the sensualist become something of a lout. To have the whole thing add up, like—what?—seven years of Seinfeld episodes, to something in which no lessons are learned and in which there is no hugging.

The problem begins in “Star Love,” in which quirky first appears, and utterly takes hold in “Abingdon Square,” by which point in our story things get strained. By which point our potential lovers are made to wait on a perfect, magical Manhattan corner while a scene of a film is shot on the street in front of them. It gives them time to linger, it gives them time to lust, as the camera rolls.

It is a moment better suited, perhaps to that movie in which a guy named Harry met a gal named Sally, but, no, not here with all the Sebastians and the Julias.

And what about the Julia of this story? That girl in Abingdon Square? Think Annie Hall in a black cocktail dress, slightly tipsy and a little mean.

The reader, I think, is meant to ache along with the aging Paul, and, likely, with the author, while this Julia just rolls her eyes. But no—just no.

Which means that when the reader reaches the twisty, Shyamalan-esque ending, he shuts the book more firmly than he usually does. And sighs.

In assessing the work as a whole, let’s be clear, Enigma Variations is an excellent, if spotty thing. Andre Aciman is a writer of such skill that he is incapable of writing anything less than thrilling, even if only in part.

But, finally, to steal a great line from someone—could it have been Oscar Wilde?—who wrote of the difference between comedy and drama, sometimes the difference between a work of genius and one that mostly promotes irritation is where the reader chooses to stop reading.