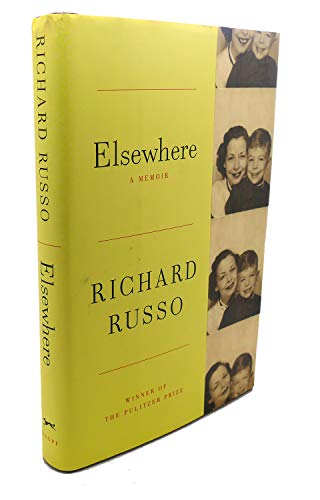

Elsewhere

“Moving? At times. Hilarious? Never.”

It’s been said that writing something down can be cathartic. I can only fervently hope that’s true for Richard Russo. For while the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist’s memoir is being marketed as “hilarious” as well as moving, Elsewhere is anything but.

Mr. Russo’s style might make it an easy read, but his subject matter is emotionally grueling.

Overall, though unintentionally, Elsewhere: A Memoir is an indictment of a mother who demanded and received her long-suffering son’s attention whenever she wanted it, right up until her death, often at the expense of his marriage and family.

From the time Mr. Russo’s mother insisted on joining him when he went to college, leaving Gloversville (“a place that’s easy to joke about unless you live there”), until she died, her yearning was always to be “elsewhere.” And her too-devoted-for-his-own-good son was always there to pack, ferry, and make it happen for her. He was even her regular grocery shopping chauffeur. Because, as she constantly reminded him: “There was only one person in the whole world who really cared about her, who understood and could help her, and that was me.”

Unfortunately, what’s clear in this memoir—but what its author never quite seems to grasp—is that there was only one person in the world she cared about. Herself.

From early on, he wondered how much of a burden he was to his mother, who, he suspected, “if she hadn’t been saddled with me,” would much rather be out having fun.

Apart from foisting all of her neuroses onto her overly devoted son, she was, he says, forever misjudging “not just distance and direction but the sturdiness of the barriers erected between her and what she so desperately desired. I should know. I was one of them.”

How the author’s wife, Barbara–despite her own forebodings—put up with it all beats me.

At one time, early in their marriage, the couple were living in a cramped mobile home in a trailer park and still this selfish woman imposed herself on them.

“Each night there were three of us at the dinner table, but mostly my mother talked to me as if Barbara wasn’t there. It was almost as if she’d forgotten I was married . . . ,” he writes.

Bulls**t. She hadn’t forgotten at all.

In case readers misunderstand, Mr. Russo assures us (or himself?) that his mother didn’t dislike Barbara; in fact, he explains, she often thanked her for sharing her home.

“It was my wife’s existence she couldn’t account for, as if she were a hologram.”

As for the author: “Ricko-Mio,” she would tell him. “Always there. Always my rock.”

Far from being helpless, she seems to have been a mistress of manipulation, pulling the strings of her own parents when they were alive, controlling her son through her mind games.

Mr. Russo’s (absent) father was the only one who seemed to have her measure. She’s crazy, he told the author when he was 21. Initial anger turned to relief, he recalls, “and, finally, I felt guilty. That I’d come to the same heartless conclusion as my father was a terrible betrayal, surely.”

By then I wanted to slap the blinkered wimp.

Even when he finally recognizes himself as her principal enabler—far too late in his mother’s life and his, too, I’d say—it’s pretty clear he’d do it all again.

“Over the years, as she wove herself more deeply into the fabric of our married lives, my wife also came to understand that I was aiding and abetting her demons. In fact, she warned me of this repeatedly, for all the good it did her.”

His memoir, Mr. Russo admits, is far more his mother’s story than his. Unfortunately, her overwhelming anxieties and demands, forced on to him during her life, seem to consume him still, even after her death.

Moving? At times. Hilarious? Never.