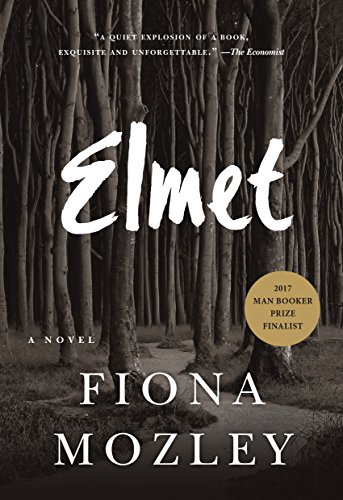

Elmet

Fiona Mozley's lushly written, yet perfectly understated debut novel, Elmet, opens with a young boy on the run. From what or from whom is not made clear in the opening pages of this 2017 Man Booker Prize finalist, but in language reminiscent of Cormac McCarthy's 2007 Pulitzer-prize winning The Road, this novel opens on a high note:

“Rain comes then stops. The weeds are drenched. The soles of my shoes squeak against the grasses. If my muscles begin to ache I do not reckon with them. I run. I walk. I run some more. I drag my feet. I rest. I drink from alcoves into which the rainwater has pooled. I rise. I walk.”

As the backstory begins to unfold, thus slowly explaining how the novel's narrator—14-year-old Daniel—has come to wind up on the run, the reader is introduced to Daniel's father, John, and his older sister, Cathy.

The three live in a copse “in a small house that Daddy built with materials from the land here about . . . far enough not to be seen, close enough to know the trains well.” It is a slow accumulation of events—a fight Daniel and Cathy get into with some older boys at their school, the disappearance of their mother, and the death of their Granny Morley—that prompts Daniel's and Cathy's gentle giant of a father to move them into their secluded house in the woods, one where the children spend their days helping with farm chores and where they're occasionally home-schooled by their only neighbor, the reclusive and eccentric Vivien.

What makes this novel stand out, however, is its dense palette of language, layer upon layer of image and visual description that transports the reader into an almost dreamlike world where, for example, when John decorates the trees in the copse for Christmas one year, it results in this striking image: “The upper three quarters of each bottle-lantern allowed air to move around the flame, and each glowed rich amber, while the light from their fellows allowed the bottles’ oil to glimmer too, dancing and refracting as the oil slowly swirled to follow the current up the wick and to the flame, as slow as still water shifting with the earth's tilt. It was a beautiful spectacle.” It is descriptions like this one, with which Elmet is filled, that indeed make the novel itself quite “a beautiful spectacle.”

But as the pastoral poet Robert Frost once warned, “nothing gold can stay,” and this Edenic world slowly starts to unravel when a brutal landowner, Mr. Price, shows up to stake his claim. The reader learns that John used to work for Price; and as the pressure on John slowly mounts, he is forced into a final act of servitude that has the potential to end his and Daniel's and Cathy's entire idyllic existence.

Tied up into the conflict with Price is a bit of a political thread, one in which the reader sees Price’s greed and his resulting mistreatment of his many tenants and workers. These folks ultimately come together as a sort of labor union, with John becoming their unlikely leader and hero, a sort of Robin Hood figure.

The author even alludes to “Robyn Hode and his pack of scrawny vagrants, whistling and wrestling and feasting as freely as the birds whose plumes they stole.” But while the suggestion of workers' politics is there, the novel never reaches the point of becoming didactic or preachy. Mozley, like all good novelists who are able to practice restraint, leaves it up to the reader to draw his or her own conclusions.

Instead the novel's focus seems to be on those rare, tender moments between a loving father and his children, for whom he'll do anything to protect. But this not at the cost of sacrificing experiences such as these, for example, wherein the trio spends quality time together in the kitchen, cooking potatoes until “the skin becomes crisp while the white flesh on the inside melts like hot dollops of cream, not far in texture from the butter we would drizzle over the tops. Daddy sorted most of the meat but I ground offcuts and entrails and made little patties with barley and spice.”

It is quite refreshing to read a novel that, again to reference Cormac McCarthy's The Road, portrays fatherhood as the ultimate and best sacrifice one can make for one's children. To know that one can still create a world, a sanctuary, wherein all is well, even if danger looms in the distance. A special place headed by a father who “would never, not ever, leave us again.” And even though this sentiment might very well crumble under its own portentous weight, the feeling it evokes is certainly worth believing in while it lasts.