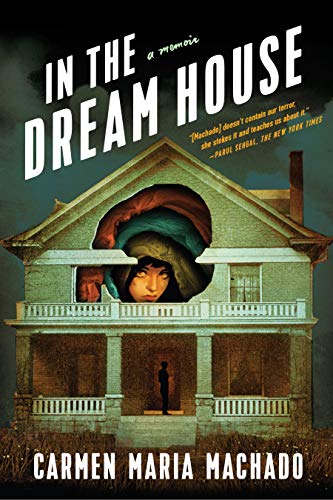

In the Dream House: A Memoir

“Machado is full of surprises.”

In the prologue to Carmen Maria Machado’s much anticipated second book, In the Dream House, she quotes critic Saidiya Hartman, “How does one tell impossible stories?” Machado’s answer is a memoir in flash pieces, each chapter reframing her story of “domestic abuse between partners who share a gender identity” through a different genre or trope: “Dream House as Picaresque,” “Dream House as Bildungsroman,” “Dream House as Famous Last Words.”

Machado meets a woman while studying fiction at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and falls into a “crevice,” an abusive relationship that takes years to escape. She attempts to make meaning of this impossible relationship within one genre, then discards that genre and tries another one. But no one genre or trope can hold the full reality and truth of her experience. Like Goldilocks, she tries each chair and bed, but unlike Goldilocks, none are just right. This twisting love cannot be fully contained in one container.

Although the jacket copy calls the form “wildly innovative,” it actually has much in common with Montaigne’s 16th century essays. Michel Montaigne combined autobiography and intellectual ruminations in what we would now call flash form. He called his pieces “essais” or attempts. In the tradition of Montaigne, each of Machado’s pieces is an attempt to get at her truth in a different way. In Brett Lott’s classic essay “Towards a Definition of Creative Nonfiction,” he writes, “any definition of creative nonfiction must include the form’s circling bent, its way of looking again and again at itself from all angles in order to see itself most fully.” This is an apt description of the form of In the Dream House.

While other teenagers were dating, Machado “was busy being extremely weird.” Formerly born-again religious, a “curvy to fat brunette in glasses,” Machado is initially exultant, blown away by her first consummated queer love: “You don’t know what is more of a miracle: her body, or her love of your body.”

In the beginning of the affair, the titular dream house indicates the Barbie kind, the dream of perfection, which for the young Machado is a bucolic life in the country, an idyll where she and her lover will can vegetables, make love, and write: “the perfect intersection of hedonism and wholesomeness.” But the dream house trope soon begins to invoke a frightening space that defies conventional logic, a world in which her partner is by turns furious, vindictive, and loving, seemingly without cause. Early on in the relationship Machado helps out a distraught colleague, and her partner erupts into verbally abusive jealousy, finally hissing to her, “Don’t you ever write about this. Do you fucking understand me?” Machado agrees not to, then writes profoundly and prophetically, “Fear makes liars of us all.” The memoir itself is Machado’s decision not to be bullied into silence.

Readers were first introduced to Machado’s imagination, part Shirley Jackson, part Angela Carter, all dread and red velvet, in her prize-winning 2017 short story collection, Her Body and Other Parties. Here, too, Machado’s eye tends toward the “pat-pat-pat trail of blood across the floor,” to “fur and bone” and “streaks of gore.”

Although the memoir plays with many genres, it most often uses the register of melodrama. Machado writes that she wants to reclaim it: “after all, melodrama comes from melos, which means ‘music,’ ‘honey’: a drama queen is nonetheless, a queen—but they are still hot to the touch.” If the honey sometimes threatens to become too thick, Machado cuts it with sharp, self-mocking humor.

For example, when her abusive partner moves away, Machado agrees immediately to a long-distance relationship. Writing about herself in the third person, and with a raised eyebrow, she observes, “it’s what she would call a no-brainer (The pun is lost on her in the moment.).” There are chapters titled, “Dream House as I Love Lucy” and “Dream House as Choose Your Own Adventure.”

Moving from hot honey melodrama to Lucille Ball humor to clear-eyed wisdom, Machado gymnastically tries every way she can think of to tell her hard-to-tell story, only to arrive at a brutal, elemental truth: “You can be hurt by people who look just like you.” But that heartbreaking truth is not the end of her story. In “Dream House as Plot Twist,” we are reminded that Machado is full of surprises.